AI art refers to any digital art created by a type of artificial intelligence known as generative AI — where a machine leverages algorithms to create unique images, videos, audio and written material. Trained on billions of annotated examples of existing artwork, styles and techniques, AI art generators produce creations that mimic the characteristics of human-made works.

What Is AI Art?

AI art is content (text, images, video, audio) that has been produced using generative AI. AI art generators work by analyzing patterns in existing art and then using statistical models to create new works based on these patterns.

Some artists embrace the technology and its potential, but others are fighting against it, wary of its broader ethical and legal implications. As the lines between artistic expression and technology blur, our understanding of ownership, fairness and the very nature of creativity itself is up for debate.

What Is AI Art?

AI art is digital content that has been created using generative AI. While it is more commonly associated with visual mediums like images and videos, AI art also includes written works and audio compositions.

Image generators like Midjourney, text generators like ChatGPT, music generators like Suno and video generators like Sora enable anyone to instantly conjure up realistic content in a matter of seconds — without having to wield a brush, pencil, musical instrument or camera. All you have to do is type a few words into a text box.

The inner workings of AI art generators are fundamentally mysterious, which means their outputs are often unexpected. Controlling them is a collaborative, repetitive process, where users tweak their creations with prompt engineering.

“It’s not like watercolor painting,” digital artist Lev Manovich told Built In. “You don’t have to decide every line or every brush stroke. You give it a direction and you get something — it surprises you.” From there, the user “curates” what the generator makes, he continued, refining their prompt over and over again.

The final product can be anything from a hyper-realistic landscape to a country song. In any case, these creations are often the result of numerous prompt iterations, revisions, detours and hours of work — all on the back of advancements in machine learning.

How Does AI Art Work?

AI art generators work by analyzing patterns in data and using complex statistical models to understand what the prompter is asking for, and then generating content based on those patterns. These tools use a variety of specific AI models and techniques depending on the medium, but the fundamental process of getting from input to output is usually the same:

- Training: Generators are fed a massive corpus of existing artworks, along with text descriptions. This can be photographs, paintings, books, news articles, songs, screenplays, movies and lyrics.

- Processing: Generators use neural network models to find patterns in their training data and replicate them in new content. For instance, image and video generators often use convolutional neural networks to recognize specific things in their training data and generative adversarial networks (GANs) to produce an output. They may also use a technique called neural style transfer, combining the style of one image with the contents of another to create something entirely new. Meanwhile, text generators use large language models (LLMs) built on Transformer architectures, and music generators use recurrent neural networks.

- Generating: Once trained, AI art generators can produce artwork based on users’ prompts, drawing on what it has learned to create a unique piece of content. For example, an image generator trained on pictures of apples has formed patterns based on abstract qualities like “roundness” and “redness,” which then overlap to form an understanding of “appleness.” The AI combines these relevant qualities to make a new, imagined picture, rather than just assembling bits of existing pictures.

At the end of the day, creation and comprehension are “really intricately linked” when it comes to AI art generation, Ajay Jain, chief technology officer at AI video generation company Genmo, told Built In. The data must be broken down to understand its individual parts, and then be brought back together to form new patterns and understanding.

“If a language model can generate texts similar to the distribution of texts that people have written, it’s understood something about how people communicate,” Jain said. “If a [visual] model can generate images or videos similar to the things we’ve seen in its training data, it has to understand that training data.”

Popular AI Art Generators

There are a range of AI art generators available to both casual users and professionals, including these well-known generative AI tools.

Midjourney

Midjourney is a text-to-image generator that allows artists to produce unique images from simple prompts. It can also process image prompts and multi-prompts, giving users more freedom to customize their artwork. Users can then experiment with different variables like visual style, image ratio and zooming in or out. The tool has gone through several iterations, and is currently available in its sixth version.

DALL-E 3

DALL-E 3 is OpenAI’s text-to-image generator that demonstrates better understanding than previous models, reducing the need for prompt engineering. It’s also built natively on ChatGPT, so users can collaborate with the chatbot to adjust their prompts and develop new ideas. DALL-E 3 comes with some safety features as well, including the ability to decline requests that ask for public figures by name or images that replicate the styles of living artists.

Adobe Firefly

Adobe Firefly is a multimodal AI generator that can process text, image, audio and video data. In addition to creating images from text prompts, Firefly lets users perform advanced edits, such as adding specific objects to a photo, expanding the frame of an image and tweaking elements like mood and lighting. Users can also make their content more dynamic by transforming text into short clips and tailoring audio length to fit an image or video.

NightCafe

NightCafe is a free AI art generator that gives users access to popular models like DALL-E 3, Stable Diffusion and Flux. The platform places a greater emphasis on community, providing chat rooms and daily art challenges to encourage artists to collaborate with friends and share their work publicly. NightCafe further nourishes this sense of community with accessibility, adapting to laptop and mobile device formats.

Jasper AI

Jasper AI is an AI platform that caters more to marketing, PR and communications professionals. With Jasper’s AI image suite, creatives can make detailed edits to images like adjusting the background, uncropping images, removing text as needed and even completely reimagining visuals for inspiration. Jasper can also be trained to follow voice and style guidelines, so all AI-generated content aligns with a company’s brand.

Canva

Canva offers a free AI generator tool that gives users access to text-to-image generators Magic Media, DALL-E and Imagen. Users can add or remove individual elements, apply a variety of styles and filters and supplement visuals with graphics. The Canva platform enables real-time collaboration and accessible exporting options, making this tool helpful for both everyday artists and professional creative teams.

Use Cases of AI Art

The availability of AI art generators with enhanced capabilities has made AI art a vital tool across many businesses and industries. These are some of the sectors where generative AI art has already made a significant impact:

- Marketing: Marketers can quickly craft visuals for social media posts, presentations and other marketing materials that follow company brand and style guides.

- E-commerce: E-commerce businesses can leverage tools like DRESSX, so customers can virtually try on clothes to make more informed shopping decisions.

- Architecture: Architects can develop prototypes of structures, refining their designs before transitioning to the building stage.

- Gaming: Video game designers can use AI to craft backgrounds, characters and other visual elements as part of the world-building process.

- Education: Visual arts teachers can employ AI generators to help students hone their creative skills and flesh out ideas.

- Art therapy: Art therapists can use AI art generators to better engage patients — an approach that promises to improve the quality of therapy sessions.

Examples of AI Art

From individuals interested in pushing the boundaries of art with AI to professionals who have captured global attention with their AI-generated pieces, here are a few examples of artists and artworks that demonstrate the possibilities of AI and art.

“Théâtre D’Opéra Spatial” by Jason M. Allen

“Théâtre D’Opéra Spatial” (French for “Space Opera Theater”) is an image created by game designer Jason Michael Allen, with the help of Midjourney. Combining elements of the Renaissance and steampunk styles, the image portrays people in Victorian garb standing in a Baroque-style room, gazing through a large, circular window at a sun-drenched sky. Allen’s piece became one of the first pieces of AI-generated art to win an arts competition, sparking fierce backlash and raising questions over copyright claims.

Katsukokoiso.ai

Katsukokoiso.ai is a project inspired by a Milan-based artist who combines his photography background with an interest in the abilities of artificial intelligence. His services include developing AI images for fashion brands, crafting AI art to match soundtracks and designing conceptual AI artwork. The video above is a sample of his work, along with the pieces he shares on his Instagram page.

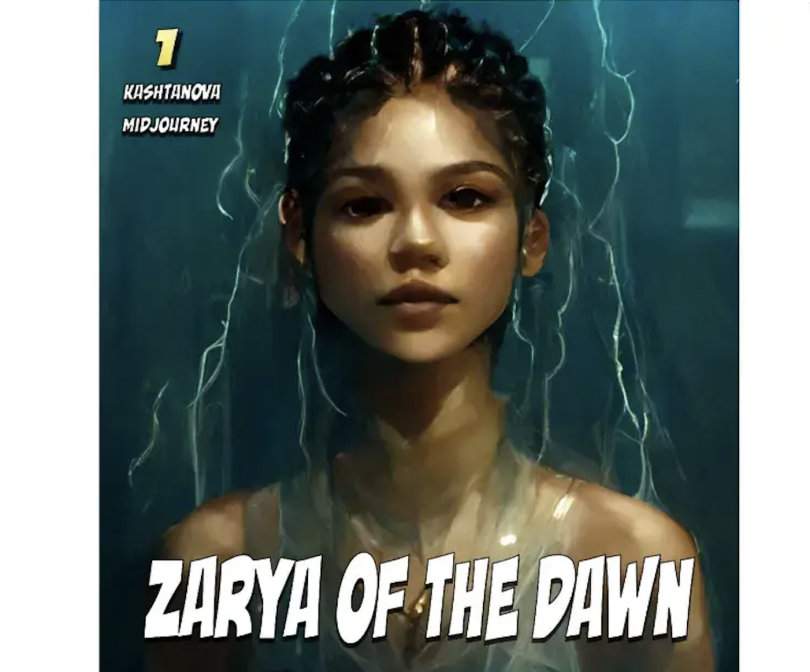

“Zarya of the Dawn” by Kristina Kashtanova

“Zarya of the Dawn” is a short graphic novel written by author and software developer Kris Kashtanova and illustrated by Midjourney. In 2022, the piece made history as the first known work of AI-generated art to be granted registration with the United States Copyright Office. But just a few months later, the office partially rescinded the work’s copyright registration, claiming in a letter to Kashtanova’s attorney that it contained “non-human authorship” that had not been taken into account before.

Kelly Boesch

Kelly Boesch is a video editor and graphic designer who uses her professional talents to craft AI-generated images and videos, which she features on Instagram. The video above is an AI-generated video that was made with the help of Midjourney and Luma AI, with the soundtrack produced via Suno. Boesch also sells AI-generated art collections through her online store, including t-shirts, posters and mugs.

“Edmond de Belamy” by Obvious

“Edmond de Belamy” is an image made by Obvious, a Paris-based arts collective, using a generative adversarial network. It became the first piece of AI-generated art to be auctioned at a major auction house, selling for $432,500 as the second-most expensive artwork in the auction behind a screen print from Andy Warhol’s iconic “Myths” series. Since then, Obvious has been accused of stealing code originally created by AI artist Robbie Barrat — something Obvious has admitted but has led to no official credit or compensation for Barrat.

The Wizard of AI by Alan Warburton

The Wizard of AI is a documentary about generative AI, made with generative AI. Most videos and images in The Wizard of AI were made with Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, Runway and Pika. Warburton explained that these tools were used to “discuss and critique the legal, aesthetic and and ethical problems engendered by AI-automated platforms.” The movie also includes real news clips and interviews with tech and art experts. Warburton wrote the script himself, reportedly drawing from research for his PhD in Digital Culture and Communication.

Julian van Dieken

Julian van Dieken brings a diverse media background to the AI field, having worked in photography, video production and media education. As part of his passion for media literacy, van Dieken uses AI tools to experiment with developing various productions. The video above was created with Runway’s Gen-3 Alpha tool and represents van Dieken’s attempts to convert AI’s glitching tendencies into chaotic visual effects.

Sunspring by Benjamin

Sunspring is a short film written entirely by an RNN-powered chatbot named Benjamin, which was trained exclusively on human-made screenplays. It was originally created by British filmmaker Oscar Sharp and NYU AI researcher Ross Goodwin in 2016 for the 48hr Film Challenge contest of Sci-Fi London, a film festival dedicated to science fiction, and was later released on YouTube by tech news website Ars Technica.

AI Art Controversies

Artificial intelligence has shaken up the art world, creating significant controversy along the way. From copyright concerns to fears of human artists being replaced, AI-generated art is at the center of several heated legal and ethical debates.

Art Generators Use Copyrighted Work as Training Data

Several human creators have filed lawsuits against AI companies like OpenAI and Stable Diffusion over the years, claiming their copyrighted work was scraped from the web and used as training data without their permission.

To establish copyright infringement, “somebody has to copy somebody else” with “substantial similarity” between the works, according to Rob Heverly, an associate professor at Albany Law School.

AI companies argue that they transform this material enough for it to qualify as fair use — a doctrine in U.S. law that permits limited use of copyrighted material without explicit permission from the copyright holder. They claim they’re not selling this work as their own, or copying it line for line; rather, they’re using it to teach their AI models — an entirely different use from the original.

But a U.S. district judge is allowing a group of artists to advance their allegations of copyright infringement against Stability AI and Runway, leaving AI companies’ claims of fair use in limbo for the time being. If the courts ultimately determine that these companies are infringing on creators’ copyrighted work, it could mean a lot more lawsuits.

AI Art Cannot Be Copyrighted

The U.S. Copyright Office has long held that works created by non-humans — including machines — are not eligible for copyright. At the moment, art created using generative AI cannot be fully copyrighted in the U.S.. Without copyright protection, creators may lose control over how their work gets distributed and used, and they may miss out on potential income since others can freely copy, modify and sell the work without permission or compensation.

The root of this issue lies in the way AI art generators work, which involves recognizing patterns in existing data and replicating those patterns in new ways to form original works of art. Their outputs are simply a culmination of other people’s work, much of which is copyright-protected in its own right.

“The guidelines essentially say that you need to have created the work,” Heverly told Built In. “If you just put in, ‘Give me a picture of a starry night,’ you haven’t done the work that’s necessary to create art. All the ‘choices’ are made by the AI. You haven’t made them.”

The lines get even blurrier when the creative work is the result of a collaboration between a human and a machine, which is often the case with AI-generated art. Under these circumstances, only the human’s contributions to the piece are eligible for copyright — not including the prompts the person used to instruct the generator.

The Technology Can Be Used Maliciously

The technology that powers AI art generators has been used to create deepfakes, which are fabricated videos and audio of real people that can look and sound convincingly authentic. While deepfakes do have some useful applications, such as synthetic data creation and customer service personalization, they are commonly used for malicious purposes: Spreading misinformation, carrying out phishing attacks and phone scams, even enacting political sabotage.

The technology has also gained notoriety for its role in the nonconsensual creation of fake pornographic content. While Congress has prohibited the unauthorized dissemination of sexually explicit photographs and videos of both adults and children, law enforcement agencies are struggling to prosecute the makers of unauthorized deepfake images because existing legislation on this issue doesn’t take into account the way this technology works.

“It’s different from other forms of nonconsensual pornography distribution, because it’s not that person’s body actually being used in the video,” Star Kashman, privacy attorney and partner at cybercrime-focused Cyber Law Firm, told Built In. “The law has to catch up to that.”

That said, some progress is being made. The U.S. Senate unanimously passed a bill that would allow people portrayed in sexually explicit deepfakes to sue the creators. The Senate introduced another bill in 2022 that would make sharing nonconsensual AI-generated pornography illegal, but that is still in its early stages.

Art Generators Are Replacing Human Artists

AI art generators pose a significant threat to human creative professionals across various industries. These tools can produce high-quality content much faster and cheaper than humans. And as their capabilities improve, demand for painters, writers, musicians and actors may decrease.

This is already happening in fields like graphic design, illustration and stock photography, with AI tools being used to create marketing materials, stock images and book covers at increasingly high rates. The music industry is going through something similar, with AI-generated background music and jingles removing the need for session musicians and freelance composers.

This was also a key issue in the 2023 SAG-AFTRA strike, where actors expressed concerns around being supplanted by artificial intelligence. In the end, union leaders agreed that studios cannot use AI tools to create digital replicas of performers without payment or approval. But they punted on the issue of using actors’ prior performances as training data, which means studios are allowed to create “synthetic fakes” — fabricated characters that meld together recognizable features from real actors — without compensating or asking permission from the actor. Screenwriters have also received some protections from AI after the Writers’ Guild of America went on strike in 2023.

While it’s unlikely that AI art generators will replace human creatives altogether, it will probably reduce the number of jobs available in these fields — especially for entry-level positions, which could make it hard for newer artists to enter these fields and establish their careers.

Limitations of AI Art

In addition to fueling controversies, AI-generated art comes with some inherent flaws that creatives need to keep in mind when using AI generators.

Absence of Artistic Originality

AI art generators are trained on data that consists of previous works, styles and other creative elements. As a result, AI art generators excel at replicating the styles of existing artists, but they don’t possess genuine creativity that defines pieces crafted by human artists.

Lack of Contextual and Cultural Understanding

AI art generators aren’t aware of current cultural trends, political climates and other contexts. This can weaken their ability to produce works that connect with viewers on a deeper level and may lead them to accidentally generate insensitive pieces.

Inability to Adapt to Changing Art Landscapes

Artistic expression is a product of a specific place and time, shifting rapidly along with larger cultural changes. Because AI art generators only have their training data to go off of, they either need to be retrained or risk falling behind the newest trends in media and art.

Data Inaccuracies and Biases

If the creators behind AI generators aren’t careful, they may train generators on data that is incomplete, inaccurate or riddled with biases. Users may then be unable to create diverse content and unintentionally produce harmful works.

Questions Over Ownership and Copyrights

AI art generators raise questions about ownership and fair use. Artists who use these tools may risk not being able to claim the final product as their own. They may also face pushback from artists whose works were used to train these generators without their permission.

Will AI Art Replace Human-Made Art?

AI art has begun to shift society’s view of creativity from something that requires high levels of intelligence and imagination to something that can be synthesized and manipulated with nothing more than some data. But not all art is simply an amalgamation of pixels and letters to look at. At its best, art can challenge us, comfort us, excite us and inspire us. It has the capacity to touch us in a profound way.

While AI is really good at mimicking human emotions and empathy, it is still a long way from actually being able to think and create like a human. And art created in seconds with a few keystrokes often lacks the same prestige as works that require real talent and effort.

“People value skills. If you [generate] some beautiful, realistic image, people will say, ‘Well, did you make it? Did you spend ten years learning how to draw like this, or did the AI do it?’” Manovich, the digital artist, said. “Craftsmanship, education, mastery is valued.”

For these reasons, it is unlikely that AI art will completely replace traditional art. Instead, art generators are expected to become tools for human artists going forward, enhancing their creative process and expanding their capabilities.

“Everybody is going to be a creator,” Genmo CTO Jain said. “There’s going to be a lot more people who are able to tell their stories that aren’t currently able to — they don’t have the means or the time necessarily.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is AI art controversial?

AI art is controversial due to concerns over authenticity and creativity, as some argue that artificial intelligence lacks the ability to captivate human expression in that way and is thus devaluing traditional artistic skills. It also raises complex issues around copyright — particularly around ownership and originality — and the utilization of existing artworks as training data. Plus, the technology used to make AI art is increasingly used in malicious ways, including phishing attacks, phone scams and the nonconsensual creation of pornographic images using deepfakes.

Is AI art legal?

While it is not explicitly illegal to produce content using generative AI, the subject of AI art continues to exist in a legal gray area. The primary issues involve fair use and intellectual property, as the legality of a specific piece often hinges on how the AI model was trained and whether the generated art infringes on existing copyrighted works. Plus, AI art isn’t protected by U.S. copyright laws, so questions around authorship and ownership remain unanswered.