After nearly three decades of painting and creating art in Berlin, Roman Lipski was stuck in a loop. An artist should always be re-inventing themself, adding new forms and techniques to tell meaningful stories. He had spent years doing just that, developing his skills as a landscape painter who told stories through architecture, nature, shadows and a monochromatic palette.

But his well had run dry.

What Lipski really wanted to do was bring abstraction and more color to his art. He’d try to add new colors and shapes to his paintings, but none of it felt right. He feared the bold colors and odd shapes would look tacky rather than professional and couldn’t figure out a way to break from his old habits. At the same time, he couldn’t stand painting in the same style any longer.

“I was stuck in the moment, stuck in time,” Lipski said.

Then he received an invitation to teach at the Berlin University of Arts. It was there, in 2016, that he met a data scientist by the name of Florian Dohmann who introduced him to artificial intelligence and its ability to create new images thanks to style transfers. This technique involves using deep learning to process illustrations, learn its design elements and then create new images in a similar style.

Lipski always considered himself a traditional artist who didn’t rely on technology. But learning about the way AI could make images piqued his interest. He couldn’t deny the fact that we use tech every day to solve conundrums. Want to figure out how to remove a stain? Ask Siri. Wondering what the fastest route is from the Brandenburg Gate to a chic Kreuzberg cafe? Check Google Maps.

So, he thought, why not use it for his own art?

Working with Dohmann, Lipski created nine paintings of the same image — a winding hillside street bathed in streetlights and surrounded by shadowed trees — each with different colors and elements. At first, he thought it would come up with a perfect evolution of his own art. Instead, the abstract images the robot produced showed him a new way forward.

“It was the solution,” Lipski said. “The way to stop my crisis was so simple. I just had to put the red, the green, the yellow in the right positions. The machine helped me to see the elements.”

AI in Art Today

Lipski’s journey reflects a growing trend of artists turning to AI to create art. The trend has coincided with increased accessibility of AI tools and open-source software. But it wasn’t until art auction house Christie’s became the first to sell an AI generated painting for $432,500 that it captured international attention.

On the surface, this can seem like a troubling trend of automating a classically human pursuit. But painting and art is also a way of capturing a moment in time, and it’s impossible to ignore the role machine learning plays in our lives today and will play in the future.

Technology has also always been a part of painting, from the invention of oil paints to paint tubes to cameras that capture images that the artist can paint from. Each innovation has expanded the possibilities and questions art can explore.

In that same tradition, artists using AI are able to delve deeper into how the human mind works, and in so doing, make the black box feel a little less alien.

Exploring Human Creativity

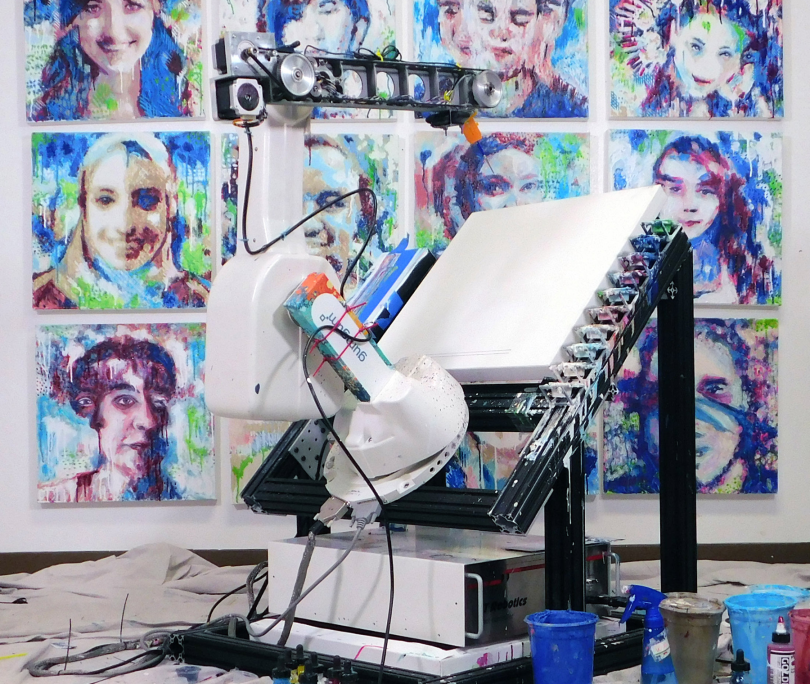

For the last 16 years, Pindar Van Arman has been teaching his AI, CloudPainter, to paint like him.

To do that, he’s had to reverse engineer his creative process and translate it into algorithms. He’s had to think about why he changes colors when he paints, how long a brushstroke should be and what makes a quality painting.

While the robot does all the work and its pieces have been evaluated by art critic Jerry Saltz, Van Arman will be the first to tell you that his AI is not an artist. And what it creates is not art because the robot painted it. But the project has allowed him to explore the nature of creativity in a way that wouldn’t be possible without AI.

“Trying to get it to paint in my style, which has been my goal, has taught me more about myself than I ever realized,” Van Arman said. “Like, ‘Why do I make certain decisions at certain points?’ And I get to ask myself why I did that and can it be coded?”

Van Arman first created CloudPainter as a way to combine his two passions: robotics and painting. Growing up, he’d always imagined himself as a painter in the mold of the impressionists like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir, but as he got older, he pursued a career in tech as a graphic designer. He then studied programming after seeing the demand for engineers in the tech industry. In 2005, he volunteered for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Grand Challenge, where he worked on coding a self-driving robot that could complete a 100-mile race in the desert.

After that experience, he decided to continue working with AI and robotics on a smaller scale at home. At the same time, he’d always loved painting but, with a growing family, found himself with dwindling free time. He designed a robot to paint backgrounds for him, allowing him to complete a painting in an hour rather than spend all day on it.

It all worked wonderfully until he came home one day to a robot with a broken paintbrush going through the motions.

“I thought to myself, ‘OK, this is a printer,’” Van Arman said. “I need to get this robot a camera. It needs to know if it’s not painting.”

He started to experiment with adding a camera and feedback loop into the process. There are currently 24 feedback loop algorithms with different artistic rules that determine what the robot will do next.

The robot paints a little, snaps a picture and then rifles through the algorithms to determine where it should add its next stroke. For example, perhaps most of the action in the painting is in the lower third of the frame. The robot’s rule of thirds algorithm will kick in and push it to balance the action elsewhere. Or perhaps it used a lot of red in one section, an algorithm might tell it to change colors to add contrast.

“I think we’re really unlocking what’s going on in our heads.”

Van Arman can also control those algorithms like levers to increase them in priority if he sees the robot doing something he doesn’t think looks good. But there are also instances where the robot is doing something wrong, and Van Arman sees those as opportunities for innovation.

“There’ll come a point where I’m like, ‘It’s doing something wrong.’ Or, ‘It’s doing something that doesn’t make sense artistically,’” Van Arman said. “Then I’ll ask myself, ‘How do I know that that’s wrong? What tells me in my mind that the robot is going in the wrong direction?’ … It might be that there’s no contrast. Can the robot ever identify the fact that there is no contrast? The answer is yes.”

In a lot of ways, the process mirrors how we operate and create things, Van Arman said.

“I might look at something and have different parts of my brain telling me different things, but the one that’s screaming the loudest is the one I follow,” Van Arman said.

But the paintings look unlike anything else. Whether it’s a portrait or abstract artwork, the robot mixes impossibly long, precise 18-inch brushstrokes with squiggly lines, creating a sense of mechanical repetition and serendipity.

Though the robot isn’t able to put any meaning into the paintings, that doesn’t mean they aren’t thought-provoking. Van Arman has been able to use the project to frame discussions around creativity, while others have looked at the images and thought about the emergence of AI and what it means for humans.

“They’ll say something like, ‘I see the fight between the fact that we’re going into a new form of consciousness and at the same time, we’re stapled to our old ways of human thinking,’” Van Arman said. “That didn’t even occur to me that that was a theme. … That’s good though because it means you made art rich enough that questions like that can be asked.”

Still, there’s pushback. Van Arman said he routinely gets hate mail from people thinking he’s trying to make artists obsolete with AI. Nothing, however, could be further from the truth, he said.

For him, his work with AI has been more like a self-portrait of the mind. The same way he’s able to create algorithms that teach the robot what to do, the robot teaches him about how we think and create.

“I think we’re really unlocking what’s going on in our heads,” Van Arman said.

Decoding AI Through Art

For experimental media artist Robert Twomey, art is an opportunity to engage with AI and make it more relatable.

In experimental media art, the goal is to create a revelatory experience through an encounter with tech. His first major AI art installation involved creating a chatbot trained as his grandmother. The idea started with wanting to experiment with limitations of AI chatbots that were becoming more popular. At the same time, his grandmother had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

He chose an existing chatbot algorithm, added her memories and conversations to its database and then conversed with it over a few months. When he was done, he presented it in a gallery, where people could converse with the bot and piece together a narrative from the fragmented responses from the chatbot.

“I thought this could be poetically descriptive of her situation,” Twomey said. “It became an interactive portrait of her, but also a self-portrait because the language was coming from me. But there were also [questions like] ‘Is there an intelligence [in the chatbot]?’ … ‘Are all these interactions with these devices like high-tech ventriloquism?’”

The project allowed him to explore the role technology plays in his own life and its limits. It’s a theme Twomey has explored throughout his career as both an artist and as an assistant professor for emerging media arts at University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

“Some things like self-driving cars, the layering of technologies and complexity of the system, is really hard to parse,” Twomey said. “Artists can create encounters or experiences that reveal some of the traits or qualities of those technologies.”

Twomey experiments with tech as an outsider. He’s only taken one computer science course in his life, though he does have a background in art and biomechanical engineering. When he starts a project, he first tries to figure out how the tool works. Over the course of experimenting with it, questions start emerging about how it works and what it can teach us.

“Those are occasions for the public, for an art viewer to reflect on ‘What can I do compared to what this machine can do?’ or, ‘Why is it behaving this way?’”

In one installation, he started working with generative adversarial networks, or GANs, which enable a robot to use deep learning to create new images. This brought to mind the way that children develop creativity. So, he trained the GAN on a series of children’s drawings. From there, an attached robotic arm created new illustrations. His 5-year-old son sat across the table from the robot and then mimicked the drawings.

The performance aimed to juxtapose art creation at a transitional phase of life and technology. First from the database of drawings from children to the GAN, then the creation of a new image and finally his own son’s process of creating his own image.

In another public art installation called the “Convex Mirror,” he set up a robotic arm and a DSLR camera inside a storefront on Amazon’s campus in Seattle. The camera then took photos for 12 hours a day through a fisheye lens and a robotic drawing tool would then draw those images.

The project was a way to expose the capabilities and shortcomings of AI. The robot could draw for 12 hours a day and freehand a perfect circle — superhuman feats in the world of art, sure. But, one afternoon, the camera sensor fell down and the machine just kept drawing the same glitched out image.

Because art is a form of human expression, incorporating AI into each of those installations was an opportunity to show direct communication between humans and machines. In doing so, he’s able to expose the incredible capabilities of technology as well as its limitations. It takes away some of the mystery and fear that prevails over AI and what it means for people.

“Those are occasions for the public, for an art viewer to reflect on ‘What can I do compared to what this machine can do?’ or, ‘Why is it behaving this way?’” Twomey said. “There’s a lot of opportunity for understanding of the mechanisms and technologies there.”

Using AI as a Muse

When Lipski started training the AI on his art, he didn’t want to learn anything about the way the algorithm worked. He wanted to be surprised by what the machine produced, but he also saw himself as a painter, not a digital artist.

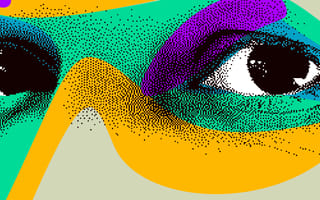

After feeding it nine iterations of the hillside street, the machine went to work producing new images via a style transfer. What came out surpassed his expectations. The pictures had elements of his painting and style, but they were distorted with bright, bold colors and abstract forms. It felt like meeting a future version of himself who had figured out how to paint in an abstract style.

“It was a wonder,” Lipski said. “The results were coherent with my own style. [I thought], ‘This is the future.’ I could also paint like this, but I needed some more time. Two or three lives, for example.”

The pictures broke him out of his creative crisis. He was able to study the strange shapes, bright colors and more open composition and incorporate some of those elements into his own paintings.

“The greater part of the cooperation between man and machine is the human because we determine what should happen.”

Still, working with AI has raised some uncomfortable questions for Lipski. For a while, he wondered who the real painter was — him or the machine? It’s forced him to confront what it means to be creative and to be an artist.

Over time, he’s come to terms with the fact that the AI has helped him unleash his own creativity. But it’s his art the algorithm is learning from, and he’s the one who decides what elements are worth incorporating into future pieces.

“I recognized that the machine is very powerful, but the artist is the human part of it,” Lipski said. “The greater part of the cooperation between man and machine is the human because we determine what should happen.”

Working with the algorithm, Lipski has come to think of it as his muse. Though it can’t feel or think for itself, it has helped him bring emotion and feeling back into his artwork after a long period of creative blockage.

This idea that AI can be a collaborator is something Lipski has worked to bring to the public with an interactive project called “Unfinished.” In it, Lipski coaches a visitor through creating their own painting starting with inspiration from an image his AI generates.

From there, Lipski assists the person through creating that painting, teaching them how to add abstract elements, different brushstrokes and color to make it pop. To top it off, Lipski then adds his own style to the artwork. The finished piece is then credited to both the visitor and Lipski.

His goal is to help people see that AI isn’t something to fear. Instead, it can help you unlock your own abilities.

“For me, it’s very important in my cooperation with machines and using AI to show that the human, that the artist doesn’t have to be scared of using the systems,” Lipski said. “The opposite. If we used the new technology, we are able to … be even stronger as a person.”

Can AI Make Art?

While each of these artists have been able to find new forms of expression in their art using AI, they’ve had to wrestle with the existential question that follows AI into any profession it’s introduced — will AI replace artists?

In recent years, there’s been a mainstreaming of AI in art and music. Tools like ArtBreeder allow people to tap into machine learning to generate and modify art so that you don’t have to connect with a computer scientist or understand open-source tools to use it. Other tools like GigaPixel AI and AI Image Upscaler use AI to help photographers enhance the size of their images without losing the resolution quality.

Such common uses of AI in art has brought up many questions about the nature of creativity and what that means for humans.

For Lipski, Twomey and Van Arman, AI is more like a really complex paintbrush than a competitor. While algorithms can produce aesthetically pleasing artwork through style transfers, art isn’t about beauty, Lipski said. In his opinion, it’s about asking questions and creating something that makes the world a better place through communication and expression.

Van Arman does believe, however, machines have the ability to be creative because creativity is about solving a problem without using brute force. In that way, he explains, Google Maps is creative because it processes vast amounts of information to find the most efficient route from point A to B for users. And the same is true for many AI systems that produce illustrations.

While he strives to push the boundaries of AI creativity with CloudPainter, he’s adamant that no AI today has the ability to be an artist — no matter how many AI paintings Christie’s sells. In fact, he gets frustrated with any artist who proclaims that their AI can “create art.” That’s because art is about one sentient being trying to communicate something to another sentient being.

A person could smash a cupcake against the wall as a way of communicating how they feel that day, and that would be art, he said. But a robot can’t decide to communicate something without human involvement. In that way, it’s a useful tool to reflect what makes us human and the way we shape AI rather than a replacement of artists.

And the day that AI can create art won’t be notable because it produced art, Van Arman said, “What will be amazing is that we have a conscious robot.”