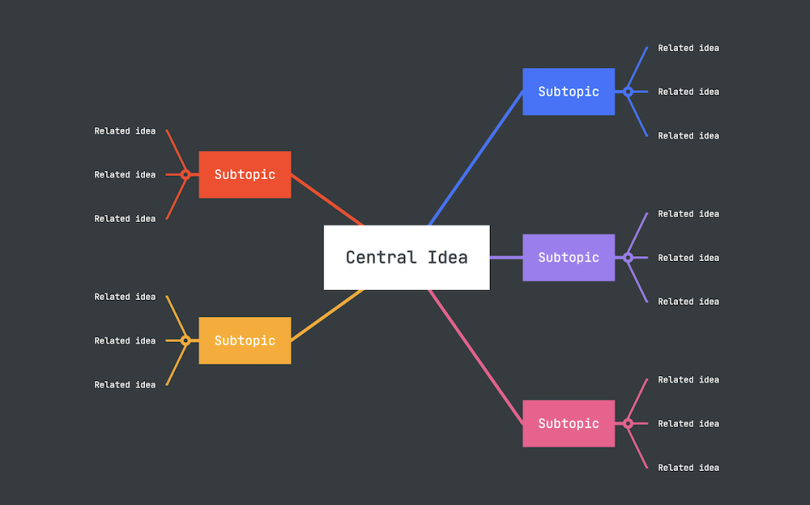

A mind map is a diagram that visually displays the mental associations the human brain makes between different ideas, representing these associations with a central idea and related subtopics connected by curved lines. Because of its intuitive nature and simple visuals, mind mapping has also found a place in some approaches to product development, where it could be applied to brainstorming new features and aiding team alignment.

What Is a Mind Map?

A mind map is an information diagram in which subtopics, subconcepts or associations stem, branch-like, from a central concept or item. They are similar in structure to hub-and-spoke networks and spider diagrams.

Michelle Matus, product marketing manager for mind mapping app MindMeister, said that, along with software development and product teams, the bulk of the company’s business-sector base includes marketers, creatives and consultants — all of whom often use it for conceptual-stage ideation.

“At the start of a project, people kind of use it as a brain dump, where they’re able to throw in keywords, random thoughts, tidbits — kind of a free flow of ideas, which you’re able to then structure into topic categories,” Matus said. “You can take this really expansive look, with an infinite canvas of all of your ideas, and then start to organize and categorize.”

What Is a Mind Map?

A mind map visually depicts the mental associations one intuitively forms between related ideas. At the heart of a mind map is the central hub idea. From there, “nodes” and additional sub-categorical “nodes” branch off, often radially. Each node sums up an idea using a keyword or phrase, allowing the creator to add context to an idea and quickly remember information without producing clutter.

The technique was popularized in the early seventies by the late Tony Buzan, who saw mind mapping as a note-taking and brainstorming technique that could aid recall better than traditional, linear outlines. It has since found greater business-world adoption in project management, product and design ideation and knowledge management.

What Is Included in a Mind Map?

Today, teams have a variety of mind-mapping tools at their disposal, but much of Buzan’s best-practice advice has endured. The characteristics he put forward now provide the foundation of the traditional mind map.

Main Topic

At the center of a mind map is a main topic or theme. Whether it’s a title or a single thought, the main topic should only be a word or a short phrase. This conveys what the mind map is about and acts as the unifying idea that relates all associations to each other. The creator can use the main topic as a way to start generating other related ideas, and readers can also more easily understand what the core focus of the mind map is.

Radial Tree of Associations

A creator can then draw associations, which are lines that branch out from the main topic in different directions and contain related subtopics. The first wave of associations should hold subtopics that are closely connected to the main topic. Additional associations may then stem from each subtopic, but those will have a less direct link to the central idea. Creators may repeat this process, but it’s best to create no more than seven levels of associations.

Curvy Branches

The lines of associations function best when curved because human brains tend to prefer curved over straight lines. Curvy branches can also end in a straight line before curving into the next association, providing a space for a creator to write down a brief thought or idea.

Concise Keywords

Ideally, each association represents an idea using a keyword, which can be a single word or a brief phrase. Producing a large block of text can make the page feel crowded and make it difficult for audiences to navigate the mind map. Emphasizing concision prevents clutter and allows a creator to more organically produce and tie ideas to each other.

Images and Colors

Colors and images can make a mind map more engaging, allowing readers’ eyes to quickly scan branches and see how thoughts are related to one another. Adding small pictures next to keywords and making each branch a different color can then reinforce groups of mental associations and make a mind map more effective for both the creator and readers.

New Mind-Mapping Software Features

At the same time, mind maps have evolved to fit contemporary work demands. Creators of mind-mapping software should support in-map file attachment, prioritize exportability to other tools and, ideally, include an in-tool communication feed to maximize collaboration. Matus said that presentation modes are also vital. Needless to say, users should make sure that whatever tool they opt for integrates with their productivity suite of choice, be it Google Workspace, Microsoft 365 or another option.

Some mind-mapping tools have even begun incorporating other information diagrams. For example, brainstorming software XMind now supports Ishikawa (or fishbone) diagrams, which can be useful for analyzing cause and effect, and timeline graphs, which are tailored to project management, Anne Zhu, XMind marketing specialist, told Built In.

Perhaps most important is the ability to transition from the conceptual environment of a mind-mapping tool to a task management framework — that is, to go from planning to action. In 2015, MindMeister launched MeisterTask, a Kanban-style board that integrates with the mind-mapping app. Users can turn nodes, or topics, in mind maps into tasks and add them to the lean-board layout.

When to Use a Mind Map

The way professionals approach mind maps has evolved significantly since it was first championed as a memory and creativity hack. They’re still used to facilitate problem-solving and idea generation, but mind maps now encompass a much broader territory.

Brainstorming for User Experience

Prominent UX consulting firm Nielsen Norman Group recommends trying out mind maps — or similar diagram techniques like concept maps and cognitive maps — for linking associated items during early stage concepting. Mind maps, specifically, “are helpful when doing categorical ideation work,” like information architecture on a webpage, or tacking what’s included in an FAQ or privacy policy section, wrote Sarah Gibbons, NNG chief designer.

Presenting Internally or Externally

Milligan Partners, a Texas-based technology consultant, uses mind-mapping software to quickly communicate the overall thrust of a strategy. Managing partner Matt Milligan and his team often show potential clients a partially complete mind map and invite them to help fill in the missing elements. Most mind-mapping tools include a presentation mode feature, which lets users create slides from branches and topics, “but having the map itself as a visual aid is great because everything is right there on one page,” Milligan said.

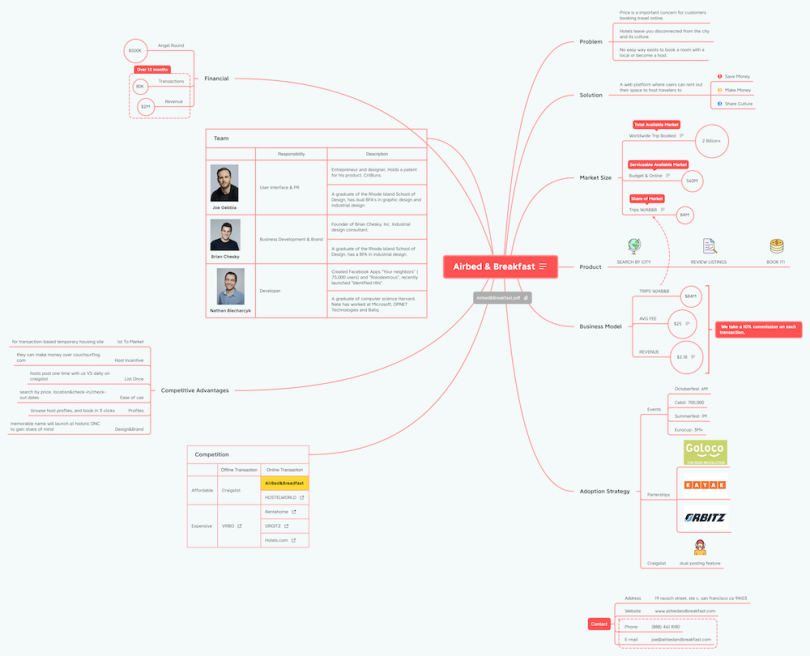

Below is a presentation mind map that XMind created and shared with Built In, about Airbnb. Including images, links, notes and pertinent files will help make the presentation more engaging.

Onboarding New Employees

Julie Harrison, growth marketing lead at Corel, an Ottawa-based graphics and illustration software company, recommends mind mapping as a way to streamline and centralize onboarding. A 2019 blog post includes a map that Harrison created in MindManager for a then-new hire. The topic branches are goals, process overviews, current projects, team, resources and HR/administration.

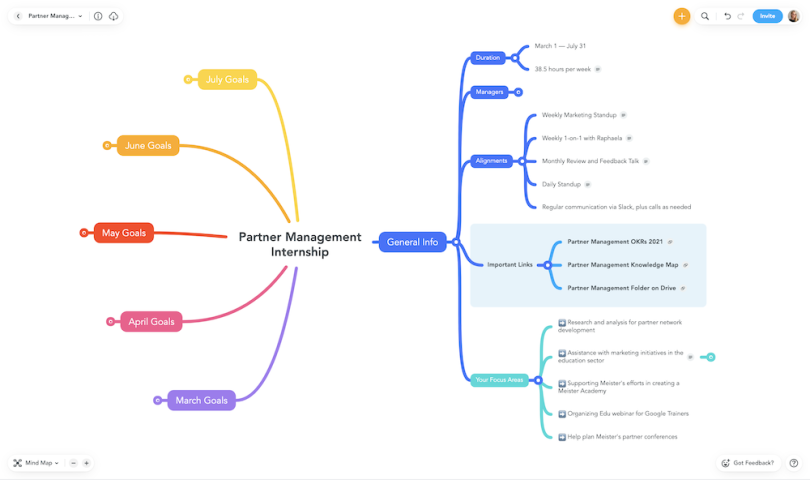

MindMeister also uses its tool internally for the same purpose, creating maps with topic branches that cover details like general company information, role-specific information and a plan for the new employee’s first five months, which includes space for feedback.

“We create a knowledge base that also becomes a space to really get an overview of the person's onboarding journey,” Matus said.

Managing New Projects Across Departments

Along with onboarding, Matus makes a mind map for every new feature launch. The central topic is the feature name. From there, individual nodes branch out for each department involved (marketing, customer success, product and so on), with subtopics for each (such as promotional channels and creative assets required). “Then we share it with each stakeholder … and asynchronously plan and brainstorm,” Matus said.

Designing Organizational Charts

Organizational charts are another intuitive use case of mind maps since hierarchical relationships are a hallmark of the system. In an org chart, a CEO might be the central idea, with C-suite and VP-level roles making up the first nodes, followed by titles one step below in rank (senior marketing manager, email marketing manager, etc., underneath the chief marketing officer).

How to Create a Mind Map

- Determine a main topic and draw or place it at the center of the page.

- Develop several subtopics — closely related thoughts or ideas — and place them on the page, encircling the main topic. Summarize each subtopic using keywords or phrases.

- Draw curved lines connecting the main topic to its surrounding subtopics.

- Brainstorm several ideas for each subtopic, linking each subtopic to its next wave of subtopics with curved lines. This next level of subtopics should also be summed up in a keyword or phrase. Repeat the process until all main ideas are exhausted.

- Add colors to the tree of associations and place images next to keywords to make the mind map more organized and easier to scan.

- If using mind-mapping software, rearrange and edit elements as needed to further organize the mind map.

Challenges of Mind Maps

While mind maps can be productivity boosters for teams, there are still concerns to consider when applying this method.

Inaccurate Scientific Basis

In the nineties, Buzan’s mind-mapping approach was positioned as a way of unlocking imaginative thinking for businesses that prioritized logic and analysis at the cost of innovation. The framing mirrored Buzan’s pitch, which emphasized brain lateralization (left brain versus right brain) and the picture superiority effect (the idea that images are more memorable than words) — pop-science tropes that today draw more skepticism.

Such reliance on “bad science” irked skeptics like former Guardian education columnist Philip Beadle, who also criticized Buzan’s penchant for grand claims and self-marketing. (Buzan developed a lucrative brand that included seminars, instructor training and over 120 books.)

Over-Exaggerated Effects

Beadle did acknowledge a degree of utility in mind mapping despite Buzan’s over-the-top tendencies. “It is a shame that perfectly good teaching tools are constantly being justified with hokum references to neuroscience,” he wrote in 2006.

In Moonwalking with Einstein, Joshua Foer’s 2011 book about memory, the author also finds the device to be helpful, though unfortunately burdened by hyperbole.

“My own impression of mind mapping … is that much of its usefulness comes from the mindfulness necessary to create the map,” Foer wrote. “Unlike standard note taking, you can’t mind map on autopilot. My sense is that it’s a reasonably efficient way to brainstorm and organize information, but hardly the ‘ultimate mind-power tool’ or ‘revolutionary system’ that Buzan makes it out to be.”

Different Collaborative Preferences

Matt Burns, a senior manager at work management platform Monday.com, recalls working with four associates on customer success initiatives, which he often diagrammed as mind maps during formative stages. Two of the four stakeholders involved engaged with the maps, contributing subtopics and cross-links; the other two, however, rarely even checked the map. Meetings that were intended for brainstorming played more like rote status updates.

“It took me a minute to realize that they just didn’t like this,” said Burns. “The format wasn’t working for them. I didn’t take the time to level set … then choose whether to make a visualization or a more traditional bullet-point outline.”

One potential solution for this issue is to explore tools that come with an outline feature, which allows users to convert mind maps into bulleted or alphanumeric lists that still preserve the hierarchical relationships between topics and subtopics.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is on a mind map?

A mind map consists of a main idea placed at the center, with related ideas or subtopics branching out from the main idea. Curved lines connect the main idea and subtopics, and each idea or topic sums up a thought in a keyword or phrase.

How do you create a mind map?

- Determine a main topic or theme and place it at the center, summarizing it in one keyword or phrase.

- Develop subtopics and place them around the main topic, also summarizing each subtopic in a keyword or phrase.

- Connect the main topic and subtopics with curved lines.

- Create several ideas for each subtopic, represent each idea with a keyword or phrase and link them with curved lines. Repeat the process until all relevant details are included.

- Add colors and images to the mind map.

- If using mind-mapping software, reorganize and edit elements as needed.

Does mind mapping work?

Mind mapping can be a convenient way to visually organize thoughts or ideas in a way that is accessible to various audiences. Teams interested in mind maps need to consider individual preferences and whether mind maps are best suited for their specific context.