Key co-founder Evan Wayne might follow Kim Kardashian’s Instagram feed, but he doesn’t buy Skims.

Why does this matter? Because, as a consumer, he exists outside the body-shaping garment’s core market segment — a fact that might elude the brand’s marketing team if it relied solely on the crude data most social sites share with their end users.

“She’s posting about content specific to a brand,” Wayne said. “That does not apply to her 100 million followers; that [applies] to a segment. And unless you know that segment and are able to disaggregate the data silos the platforms are using, you’re not helpful.”

Serving rich psychographic data to content creators is one way Wayne believes Key, a pay-per-view streaming service, can differentiate itself from social media apps and streaming platforms like Cameo that host exclusive celebrity content.

“We’re not just a live-streaming company,” he told me. “We are a place for talent to become more intelligent, a place for them to take back control of their data and for them to understand who the audience is. Do your fans wear Levi’s, or do they shop at Gap? Do they drink Dunkin’ in the morning or Starbucks? That data helps lead to new brand deals.”

As virtual events continue to thrive during mandated social distancing, Key is positioning itself as the medium of choice for celebrities and brands to share exclusive video content. Through ticket fees and brand sponsorships, celebrities can monetize behind-the-scenes moments — like a ride on a tour bus, a quick post-game video or an in-home cooking demo.

In a bid to attract and promote A-list talent, the company recently partnered with OneTeam Partners, a company founded by the National Football League Players Association, Major League Baseball Players Association and RedBird Capital Partners. The firm manages the commercial licensing rights to the names, images and likenesses of some 4,000 professional athletes featured in Electronic Arts titles.

Meanwhile, the Chicago-based startup is steadily expanding its presence as a community engagement platform. In October, it livecast a Get Out the Vote rally in Chicago’s Grant Park. To raise money for families affected by police violence, Key hosted a Black Eyed Peas remix of “Where Is the Love?” as a charitable event.

Skeptics might wonder whether Key can create a sustainable venue for “snackable” celebrity content. Do consumers have an appetite for it? And are browser-based web integrations, data insights and moderated fan interactions enough to set Key apart from streaming platforms like Quibi that folded in the face of lukewarm consumer response?

Wayne and co-founder Stephanie Biegel think the answer to both questions is “yes,” and the reason has to do with a user-experience design that gives fans an interactive outlet to connect with celebrities and brand influencers, while providing talent access to first-party data that helps them reach targeted market segments. Here, they share three key takeaways.

Experiences Are Accessible Without an App or Subscription

Back in 2019, Wayne listened to Quibi’s founder Jeffrey Katzenberg and CEO Meg Whitman regale the virtues of the celebrity streaming service at the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity in France.

“I was so bullish, because I thought: ‘It’s snackable content. It’s high fidelity. It’s going to be amazing,’” he said.

It didn’t turn out to be so amazing. Six months after its April of 2020 launch, Quibi shut down after failing to catch on with customers. But Wayne told me the celebrity streaming service made some key mistakes, beginning with charging a subscription fee. And that take has informed Key’s product development and pricing strategy.

“They’re not wrong in their shift to short form,” he told me. “The difference is the amount of subscriptions out there now is a total mind game. I have Spotify, Pandora, Netflix, Amazon, right? I have kids so I have Disney+. There’s probably some I don’t even know about.”

People don’t want to pay for another subscription service. And celebrities don’t want to churn out new content at such a grueling pace. So Key gives more production control to talent.

As its name suggests, the service functions like a key, or backstage pass. If Cameo offers a way for fans to connect with actors, reality stars and athletes through personalized videos and live chats, Key allows celebrities to create tickets to their own curated events.

“There are the Patreons of the world, there’s YouTube, there are a lot of platforms out there that have subscription models that are not necessarily advantageous to the talent.”

“It’s very similar to pay per view — where essentially you’re buying a ticket, you’re buying access to a unique individual event for talent that you love, versus having to subscribe to a channel,” Wayne said. “There are the Patreons of the world, there’s YouTube, there are a lot of platforms out there that have subscription models that are not necessarily advantageous to the talent.”

For fans, the pay-per-stream model is lower cost and lower commitment. And, importantly, Wayne said, Key is device agnostic and doesn’t require an app download.

While mobile apps are expected to yield more than $935 billion in annual revenue by 2023, the bulk of that money comes from a short list of top-performing apps. Nearly 21 percent of consumers dump newly downloaded apps after a single use, and 77 percent abandon these apps just 72 hours after installing them. With limited phone storage, consumers are reluctant to go all in on new apps, especially those they use infrequently.

But Quibi, which took a mobile-first approach, may have limited itself by focusing so intently on the app experience. In its early stages, Wayne said, it wasn’t built with a progressive web design framework, meaning it didn’t have the adaptability “to travel well across devices.”

By contrast, Key takes an elastic approach toward browser functionality. Designed for small screens first, with enhanced capabilities layered on, the progressive web design is optimized to accommodate video in any environment up to 1080 pixels. Events are accessible with a shareable URL, so “anyone, at any time, on any platform, on any screen, can log in,” Wayne said.

The arrival of the iPhone 12, Wayne told me, is one of the latest and most widely publicized symbols of democratized access to high-fidelity video quality. If Steven Soderbergh’s film High Flying Bird — the story of an agent provocateur trying to end an NBA lockout — can be filmed on an iPhone 8 and pass muster on Netflix, celebrities undoubtedly can create appealing content without spending a fortune on production.

But, ultimately, Key is banking on the notion that authenticity is more important than high production value to user adoption.

“There’s a difference between, ‘This is me, in my elements, raw and authentic’ — versus, ‘Here’s a wonderfully curated short film that I need to commit to and watch,’” Wayne said. “So I think this is something that we’re trying to stay true to: We’re not trying to be the red-carpet premiere. It’s more: If the red-carpet premiere is happening, what cool things are happening backstage?”

Influencers Get Segmented Data Insights About Their Audiences

First-party data is worth money, and Key aims to capitalize on it — but not by selling it to advertisers directly.

When users sign up for content, they share their names and email addresses, a unique record that can be crosswalked against a credit card purchase history to determine a user’s buying habits.

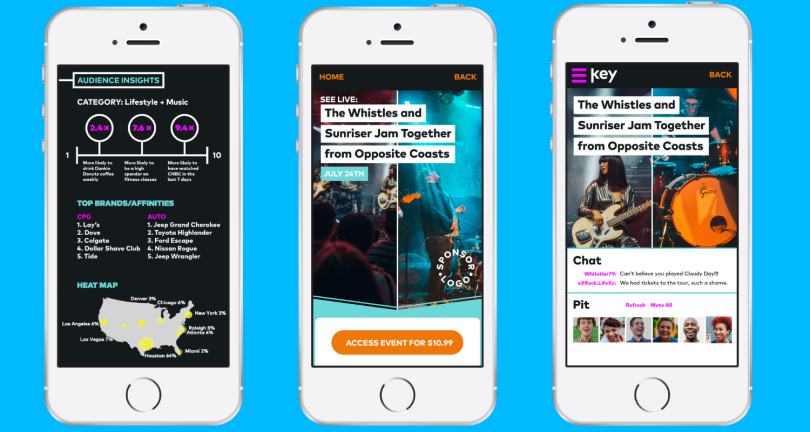

This is the same game played by countless social media companies, but the difference, according to Biegel, is Key provides the data to celebrities in a richer, more transparent format, viewable on an audience insights page. A lifestyle brand might find its audience, on aggregate, is 7.6 times more likely than the average consumer to spend a lot on fitness classes or 9.4 times more likely than the average viewer to have watched CNBC in the last week.

“Obviously, it can open up opportunities for [talent] to create brand partnerships and deals, which is kind of reverse engineering.”

Talent and brands also have access to a quick-hit list of their top affinity brands in key verticals. At a glance, they can see that their users’ purchase habits are most similar, for instance, to people who eat Lay’s potato chips or brush their teeth with Colgate. A heat map in the bottom third of the viewport breaks down the user percentage by city. These additions help talent “reverse engineer” potential brand partnerships, Biegel said, and brands become more strategic as they choose which celebrities to work with.

“I used to work in the talent space, and a lot of times, [a brand like] Pampers would come and say, ‘We want Salma Hayek because she’s a mom.’ That’s how it typically works,” Biegel added.

Content producers can also leverage the data to plan events and appearances more likely to resonate with an audience’s interests. A football player might discover their audience is drawn not just to football hype but to healthy lifestyle advice — looking at you, Tom Brady — and fold that content into their repertoire.

“We’re helping them, I think, become smarter with how they’re communicating to their audiences,” Biegel said.

With Google planning to end its support for third-party cookies in its Chrome browser within the next two years — and Microsoft, Apple and Mozilla making similar moves — the type of data Key collects from users soon could become even more valuable. Cookies are strings of code a website sends to a visitor’s browser to track their activity across multiple sites. Advertisers use them to test the performance of targeted ads, among other things.

“But when the cookies go away, which has been a big thing coming, then that driver, that unique record [of user sign-in data], is the thing that’s going to be the most meaningful for talent,” Wayne said. “Because if retargeting goes away, and the way that people message and target users goes away for brands, the most powerful thing talent can be sitting on is first-party data.”

Without cookies, Wayne said, once a visitor leaves a site, you lose the identifying information needed to message them. It’s worth pausing to note what an enormous disruption this could be to digital publishers and advertisers.

“If you’re a website, if you’re CNN, you have to now go back and talk to your audience again. [They] have to subscribe, basically, to CNN. Otherwise, when they leave CNN, you have a window, maybe, of an hour to three hours to message them. Then it’s Groundhog Day,” Wayne said.

User-Controlled Content Moderation Protects Brand Identity

Social media sites like Twitter and Facebook have taken recent steps to improve content moderation — like using warning labels to document fraudulent claims, allowing third-party groups to create anti-abuse blocklists and permanently suspending accounts, such as former president Donald Trump’s, for tweets that could incite violence.

Still, preventing abuse in text-based communities remains a massive challenge. Efforts like Twitch’s to allow live streamers to set up filters to block swear words through back-end controls illustrate how difficult it can be for private companies to determine what constitutes offensive content — and then design and encode mechanisms to prevent it.

But Key’s approach to moderation is a bit different, leaving much of the control in the hands of brands and celebrities. During an event, visitors appear to creators in a “pit” at the bottom of the viewport. They can be selectively brought into the conversation or muted. Through a feature called the ‘keybox,’ fans can ask celebrities questions and bid for a response. After the event, if a creator answers the question with a personalized video chat, they recoup a share of the bid.

Other subtle interface decisions, such as not showing audience counts, are designed to protect the reputations of celebrity creators.

“If you go on Instagram today, or Twitch, and you have that awkward moment when you’re in this room with Diplo, and there are maybe 240 people of his four million followers ... we relieve stress from that moment,” Wayne said. “And we don’t let the trolling comments come up and down, which seems to be a sensitive issue right now.”

As always, the medium is the message, and, in Key’s case, the medium is carefully curated. Colors and buttons on the interface can be customized to reflect a brand’s palette, event copy can be stylized in the voice of the brand, and creators can add options to donate a portion of ticket fees to charities or receive tips.

“If you go on Instagram today, or Twitch, and you have that awkward moment when you’re in this room with Diplo, and there are maybe 240 people of his four million followers ... we relieve stress from that moment.”

Discovery is easier than on destination apps, because the software’s interoperability allows celebrities to serve as their own marketing engines, leveraging their social channels for promotion. Users can opt in to receive notifications when their favorite talent goes live, with 24 hours to tune in after the event.

“We wanted talent to be able to activate the communities where they exist already,” Wayne said. “So when they create a link with a ‘key’ for their event, they can take that link and post it on their podcast page, their website and their social pages.”

Brands have wised up, Wayne told me. A social post on Instagram doesn’t get the play it once did, and rationalizing paid social to a CMO can be an uphill battle when the posts don’t bring in cash. At the center of Key’s business model is the notion that the company holds actionable consumer data that can serve as a bridge between talent and brand sponsors and, more importantly, validate the value of the relationship to all parties involved.

“It’s kind of nice on both ends: A brand can come to us and want to execute a campaign and figure out what talent it would like to go against. We can then use our data analysis, go to OneTeam Partners and say, ‘Of your 4,000 athletes, we’d like to leverage X, Y and Z, would they be open to it?’ And then we’ve kind of formed that relationship.”

“On the flip side,” he continued, “One Team Partners is out there pitching all the time to brands for opportunities for these 4,000 athletes, but they don’t have anywhere to execute that. So they come to us to execute it.”