Back in March, Vincent, a commercial real estate broker in his early forties, was dating a woman who grew up in France and had a passion for music. They met on a dating app, and had only been on a few dates when the coronavirus reached New York and Vincent (not his real name) decided to leave his Gramercy Park apartment to go to his family’s beach house in Delaware. He invited her, and she decided to come along.

It didn’t work out. After 10 days of arguments and near-constant rain pelting the rooftop, they reached a breaking point, and he rented her a car so she could drive back to the city.

Somewhat miraculously, they stayed in touch for a while, but eventually the relationship fizzled. Still, Vincent thinks dating apps are much better than the alternative: bars, friend referrals and ill-matched blind dates.

“I think that it makes being single, and choosing single-ness as a lifestyle, an easier choice to make,” he told me.

After talking to users like Vincent, and several product owners and designers at dating app companies, I have little doubt dating apps feel different in the age of social distancing. In-person dates have been replaced with in-app video chats and FaceTime calls. Chatting with others for entertainment or companionship, not the desire for sex or a long-term commitment, has become much more common. There are pop-up messages encouraging users to practice hand-washing and social distancing, and indicators you can check on your profile page to designate your comfort level with various levels of physical proximity.

When users do meet in person, their options for where to go and what to do are severely limited.

“I had a lot of friends go on six-foot distanced walks,” said Hilary Gardner, a New York-based tech worker who has used Bumble, Tinder and Hinge to chat with men and arrange dates during the pandemic. “But I didn’t do any of that. I met them for a drink once bars or restaurants actually reopened. Or I did FaceTime, or I just ended up having a lot of pen pals, where you’re texting forever with these guys, with the intention of meeting when COVID is over — when you thought it was going to be six weeks, not six months.”

Dating Apps Are Growing Amid the Pandemic

Like many tech products, dating apps have done remarkably well during the pandemic. Match Group, the parent company for 45 dating brands, including Tinder, Hinge, OkCupid and Match, reported an increase in downloads and subscribers from pre-COVID-19 levels in the second quarter of this year, according to an August report in Business Insider. The company saw a 15 percent increase in new subscribers for the quarter.

Meanwhile, London-based Feeld, an app for individuals and couples interested in exploring polyamorous relationships, saw a 50 percent year-over-year increase in registrations during the first half of 2020, and 120 percent growth in messages sent in March and April as compared to previous months, according to a company spokesperson.

“I’ve been on a couple FaceTime dates where we each had wine in our respective apartments and it felt safe, and you can still date. Because the one thing about COVID is that it makes you feel lonely.”

And even as dating apps present their share of frustrations — the mental load of crafting alluring profile pages, the time-consuming courting rituals of sending flirtatious texts and emoji, the psychic pain of being ghosted or rejected — many users will tell you dating apps have dramatically improved their dating lives and alleviated feelings of loneliness, especially during the pandemic.

“I’ve been on a couple FaceTime dates where we each had wine in our respective apartments and it felt safe, and you can still date,” Gardner said. “Because the one thing about COVID is that it makes you feel lonely.”

Yet, if the purpose of a dating app is for users to delete it once they once find companionship, as sites like Hinge claim, social distancing restrictions have frustrated that mission.

Allan Luchenitser, a front-end developer who lives in Columbus, Ohio, and formerly blogged about dating apps on the site Wanton Hearts, told me the time he typically waits between a match and a first in-person date — three to seven days — has been extended a week. With fewer alternatives, he and his dating partners have had to get more creative in their planning.

He invited one date on a socially distanced walk through a rose garden.

“We didn’t wear masks, but we had them on us in case we passed by people,” he told me on Facebook Messenger. “Though really, we never got within 10 feet of anyone, including each other. It was a windy day, so mega-ventilation.”

Another of his dates took place in a residential parking lot — at 12 feet apart. “We brought our own chairs (I brought a stepping stool and sat on that) and brought some food. It was kind of a picnic.”

“There were no smooches on my in-person dates,” he continued. “Maybe this will bring on an era of higher-quality dating. Maybe, for some, an era of frustration.”

Video Calls: The New First Date

To try to adapt to the new normal, many companies have launched video chat features — with mixed results — said Liz Williams, director of qualitative research at the branding and product innovation agency The Sound, who consulted on Facebook’s Like Meets Love branding campaign.

“[Video chats] are generally seen as more performative than helpful on the part of the app,” she told me. “People are burned out from video calls, generally. And there’s something interesting going on, where, in the context of dating apps, it’s an escape from work, it’s an escape from pandemic. But actually engaging with [video chats] brings you back to the negative mindset of the hard realities of the world.”

“Video chats are generally seen as more performative than helpful on the part of the app.”

The intimacy of a video call can also seem like a big leap for people who are just getting to know one another. “You’re inviting someone into your home almost immediately,” Gardner said. “You FaceTime with your friends and family; you don’t FaceTime on a date.”

And even if you do, dim or overexposed lighting, off-kilter camera angles and lag time can make the encounter seem awkward, and physical appearance — at least from the waist up — can feel painfully on display.

“The big difference is you can scrutinize the other person’s appearance a lot more closely,” Luchenister said. “When your eyes start wandering, face to face, in real life, that’d be weird. You need to maintain eye contact. Whereas, on a screen, it’s natural for your eyes to wander a bit more, so, I think, people get a more unfiltered view of the other person.”

Frequent notifications can also be off-putting, Gardner said. Speaking to me over Zoom, she held up her smart phone with the Tinder app open. A message that read “Check out the chemistry with a quick face-to-face” covered nearly the entire screen, hiding an existing chat she was having with a man she was dating.

“And it’s really annoying because you have to say you’re interested or not interested to get it to go away,” she said.

Health Precautions and Badging

But not all the new messaging is so product pushy. Many app companies have been proactive in providing coronavirus health and safety precautions through in-app messaging, and some like Grindr, a dating and social networking site for gay, bi, queer and trans communities, have embraced a new role as a forum for public education.

Monty Suwannukul, a lead product designer at Grindr, said the queer community has been confronting difficult questions related to sexual health for decades and, though COVID undoubtedly brings with it a new set of concerns, it has been taken in stride by many users on the platform who have adapted their conversations to include common questions to ask of potential partners.

“People have told us that they are sending screenshots of their negative coronavirus test results to one another, making plans to meet up outside, wearing masks — essentially echoing the same precautions [seen publicly] and applying them to their sexual health,” he wrote.

Early in the pandemic Grindr’s in-app public-health messaging was fairly low volume — “Don’t touch your face, wash your hands.” But as stay-at-home orders and shelter-in-place restrictions took hold in New York and elsewhere, messaging clarified “that staying home was still the safest way to interact,” he said.

Grindr also made some of its existing paid subscription features, such as Explore Chat and Video Chat, free to all users, and shared a COVID-related sexual health guide developed by the City of New York to help users better understand viral transmission risks.

“People have told us that they are sending screenshots of their negative coronavirus test results to one another, making plans to meet up outside, wearing masks.”

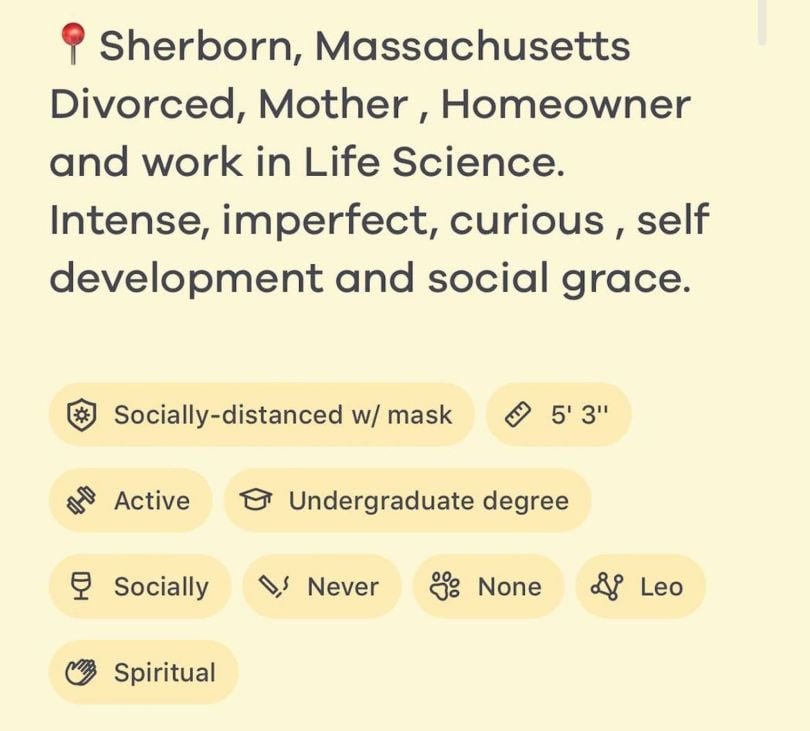

Other dating apps, such as Bumble and Hinge, feature badges that allow users to publicly share their COVID-related dating preferences. “Like, are you OK to meet up?” Gardner said. “Could we even propose that? Or, are you FaceTime only?”

Luchenitser estimated that 10 percent of users on his feeds add language at the bottom of their profiles as a kind of preemptive rejection of those who abide by different safety standards. This is similar to a development he has seen over the past four years with respect to political affiliations.

“Just straight up ‘no Trump.’ Or, like, ‘no Hillary.’ But my theory is those are the same people who are like, ‘no Covidians.’ Or, on the other side, ‘you need to believe in COVID, otherwise swipe left,’” Luchenitser said. “The international symbol for not going to go there.”

Are Sexting and Remote Threesomes Here to Stay?

While the coronavirus has changed the behaviors of dating app users throughout the world — and nearly everyone else, for that matter — it is likely that, one day, it will be a distant memory.

Selected groups have already started receiving the first Food and Drug Administration-approved COVID-19 vaccines, and the New York Times recently reported that “researchers are currently testing 58 vaccines in clinical trials on humans.”

Suwannukul said the uncertain time horizon for COVID-19 and the long-term behavioral changes it could induce in users present an interesting product development problem: “We need to be careful about over-indexing in our response. I think the question becomes: What parts of the sex and dating experience is COVID highlighting? Just like people are baking bread and regenerating little nubs of scallion, they are likely adopting new behaviors related to sex and dating that they’ll carry with them when the pandemic ends, and those are worth addressing.”

But what those behaviors look like is not so easy to track.

A spokesperson for Feeld reported that the desires users select in their profiles have changed significantly since the pandemic began. “For singles, ‘sexting’ has quickly become among the top global desires, and for couples ‘threesome’ has moved to the top of the list,” the spokesperson wrote.

But while some users are becoming more sexually adventurous online, others are returning to their exes because “there’s some level of established familiarity that feels comforting,” Williams said.

Users may also be adapting to new mechanisms for establishing trust before taking a relationship offline, or even just off the app.

“Now a woman doesn’t need to give you her number to have a video call,” Vincent said. “So that is kind of a nice thing for, maybe, a woman who’s a little uncomfortable with just diving into an in-person date.”

“For singles, ‘sexting’ has quickly become among the top global desires, and for couples ‘threesome’ has moved to the top of the list.”

And really, what draws people to dating apps may have less to do with their UX design approaches than the reputations of their user bases. That said, there are important design differences, to be sure. After a match on Bumble, women must initiate a conversation within 24 hours for the relationship to progress, Vincent said, whereas OkCupid and Tinder let users of any gender make the first move. Hinge goes one step further, allowing users to like or comment on photos before a match is made.

“So it’s kind of nice, because you could try to use your wit and personality to win somebody over, whereas the other apps, they’re just going on your photos, probably mostly,” Vincent said.

However, the more important differences, Luchenitser told me, are the real and perceived dating habits and cultural and political affiliations of the people who visit various apps.

“OkCupid is definitely like the hipster dating app. Not exclusively, but it tends to be,” he said. Tinder is “swipey.” Bumble sways toward “professional, put together” people. Match.com and Plenty of Fish lean conservative.

Market Segmentation May Be a Key Differentiator

Where app designers and developers may have the most significant influence, said Vinylly CEO Rachel Van Nortwick, is through market segmentation: creating interfaces that offer experiences and cultural meeting places that attract and engage niche audiences.

Many companies are already moving in that direction.

Feeld, which recognizes more than 20 gender identities and sexuality options in its app, has created cores where people can come together to share intimate experiences. Virtual settings with names like “Remote Trios,” “Fantasy Bunker” and “Staying at Home” let users send expiring photos, engage in group chats and designate their romantic desires.

The description on the website, as seen here, is illuminating:

Fantasy Bunker

Join If: you want to skip the small talk ?

Expect: more reasons to wash your hands. #SextandSaveLives.

Remote Trios

Join If: you feel that three’s company and staying in doesn’t mean playing house ?

Expect: a dedicated space for couples and singles looking to play together.

* * *

“We found that our virtual core users, on average, make 50 percent more connections than users ‘located’ in London — a real location core,” wrote a company spokesperson. “What we take away from this is that people will always seek meaningful connections with others, especially when we, as humans, are facing challenges on a global level.”

And there are plenty of ways to differentiate a dating app.

Grindr hosted two in-app digital festivals, for Pride Month and Halloween, that featured live music performances, exclusive content, free features, drag shows and celebrity speed dating. The festivals surfaced at the top of the display.

“For Pride we ran an event each day, sometimes this was a live performance, other times it was free features,” Suwannukul wrote. “As this also coincided with the Black Lives Matter protests, we had panels with activists from around the world. This filled a need as Pride celebrations around the world were canceled due to the pandemic; the isolation of social distance actually made our digital celebration more compelling and necessary.”

Vinylly, an iOS and Android app that pairs users based on their Spotify streaming data and other musical interests, has created new visual metaphors that speak to its target users.

The app replaces swipe matching with options to “play,” “skip” or “shuffle” potential connections. Users can discover new music and dating partners by browsing others’ playlists, and clicking a calendar icon triggers an option to search concert listings by location, venue or band. Performances can be recommended to matches as early date suggestions.

When live concerts went on hiatus, Vinylly turned to a live streaming option. Mobile users with the most recent iOS and Android updates have access to a split screen display, where they can chat on the open Vinylly app while watching a performance on Facebook Live, Twitch or another live streaming platform.

“Our long-term goal is to become a sort of destination for music and culture, because some of the other apps — and this is not a judgment at all because they work really well — but a lot of times there is a sort of stigma, with saying, ‘Oh, hey, I met on X app,’” Van Nortwick said.

For dating app generalists like Vincent, that is not a deterrent. In fact, the power of the apps, he told me — as with any technology — is in their ability to scale, to cast a wider net of options. Having more apps only increases the odds of a good match.

For Luchenitser, the appeal is entirely different. In the end, what dating apps share, he said, is the power to vet potential partners with limited risk for social repercussions. They make it easier for reserved people, among whom he counts himself, to connect with others they can relate to.

“If you’re not particularly aggressive in the regular world, like me, and even if you are, you get a little introduction to someone before you engage,” he said. “There are a few deal breakers that you might as well know upfront. If, on their profile, someone’s like, ‘I definitely want kids no matter what.’ That’s a nice signal, right ... if you don’t.”

“And it’s awful,” he continued. “I had a lot of relationships from going to bars. Fucking around. Being crazy. Those relationships were all garbage. Because, I don’t know, if you fool around with somebody at the bar, you kind of feel like you want to try to make it work. Even if when you get sober, it’s very clear the person has no business with you and vice versa.”