Last year, I was in a bad mood after a Sunday afternoon meeting with a colleague who needed help planning a workshop. Maybe it was because I disdain working on weekends. Maybe it was because commuting from the Eastside to the Westside in Los Angeles is always a horrible idea. Or maybe it was because the thought of leading a glorified brainstorming session for C-suite execs just never sits well with me. Whatever the reasons, my mood got even worse when the car behind me hit mine so hard that my half-eaten foil-wrapped burrito flew from my backseat and into my windshield.

The driver and I immediately got off the jammed freeway to safely deal with the incident on a residential street. My car was so smashed up that the gas tank had become unhinged. Fortunately, neither of us was hurt. The other driver was insured and even apologetic. Anyway, while I stood on the side of the road feeling all my feelings with this stranger, I knew that the next task was to figure out how to process my first claim with my high-tech car insurer Metromile.

Metromile is a San Francisco–based, mid-sized startup that aims to disrupt the auto insurance sector with their innovative business model and use of telematic technologies. Instead of charging customers a fixed premium for a yearly policy, they use a low monthly base rate plus a pay-per-mile pricing fee. Even though I live in Los Angeles, I actually don’t drive very much because I don’t have a daily commute to a full-time job. So, in 2018, I decided to see how much my monthly payments would go down if I switched from a traditional insurance provider to this tech disruptor. A few days after I signed up, I received a small, wireless Metromile Pulse device in the mail. Then I plugged it into my car’s onboard diagnostic port for tracking my logistical data. In the first month, my monthly premium dropped 40 percent! I was hooked.

But now it was really showtime. The model of insurance as a product is that you pay a company to safeguard you against certain risks: unexpected health crises, natural disasters or car accidents. Often, customers don’t really interact with their provider beyond their payments until a need occurs. But Metromile is different from traditional providers in that it has different touchpoints. For example, it has a well-designed mobile app that uses their telematics technology to give drivers information about their car’s health, location and driving patterns. And as a curious UX-er, I toyed with it from time to time. But generally, when customers in the United States need to interact with their insurers, they navigate a complex bureaucratic system that is not user-friendly. So, how would Metromile treat me and my smashed-up car? Perhaps the savings were great, but could the entire product turn into a major hassle?

Typically, the first thing a U.S. driver does after an accident is call the customer support line of their insurance company. A representative takes down details about the incident and the other driver to open a claim for you on your account. This begins the process through which the insurance investigates and then pays for or reimburses you for any costs.

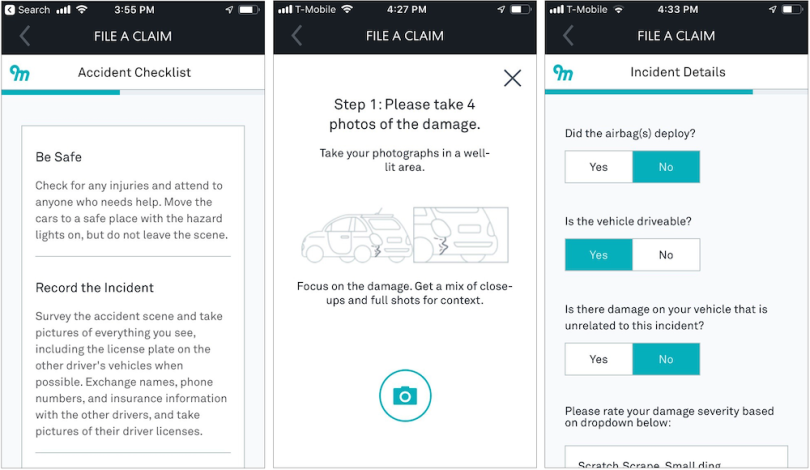

But Metromile has this process available on their app, and I was game to try it. (See Figure 1-1.) So, while I stood next to the other driver, I went through an intuitive flow that dropped me into their claims funnel. It even used geolocation for finding the exact location of the accident so I didn’t need to take note of street signs. In addition, like anybody after an accident, I was rattled. But the app’s checklist took care of everything. It made sure I collected the other driver’s name and address, took a photo of her license and car insurance, gathered any witness details, and took photos of my car and hers to document the damage. The guidance kept me calm and attentive to the matter at hand. It took less than 10 minutes.

The other driver and I hugged goodbye then parted ways. By the time I got home, there was an email from Metromile with a list of local repair shops. It also prompted me to choose a rental car provider so that they could meet me at the exact time I chose to drop my car off at the repair shop. While my car was in the shop, I drove around Los Angeles in a cool black Jeep while Metromile handled negotiations with the other driver’s insurer to help me avoid paying my own $500 deductible. Basically, somehow, this startup managed to take what is typically a very fraught customer experience for many Americans and turn it into something frictionless. And their success wasn’t just about user experience (UX) design. It was actually more about their UX strategy.

The Evolution of the Term ‘UX Strategy’

I first came across the term “UX strategy” in print in 2008 in Mental Models by Indi Young. At the time of the book’s writing, Young was attempting to help UX design ascend to a more strategic level. As such, she offered her readers a mini-manifesto along with an equation for experience strategy written by Jesse James Garrett, which you can see in Figure 1-2.

Experience strategy was a new discipline that Young and Garrett were shaping as some of the founders of Adaptive Path in San Francisco. They combined methods from disciplines including business strategy and user research. I really wanted to understand what UX strategy meant and why adding business strategy to it turned it into experience strategy.

Over the course of my career working with agencies, startups and enterprises, I’ve seen and heard many definitions of the term UX strategy. The problem with evolving technology terminology is that it causes confusion for clients, stakeholders, recruiters, HR departments, universities and, most of all, new designers. I saw the same kinds of semantic debates in the early 2000s with the conflicting interpretations of “user experience design” and “interaction design” and in the early ’90s with “new media” and “multimedia.”

What UX Strategy Was in the First Edition of This Book

In the first edition of this book, released in 2015, I said that UX strategy is the process that should be started first before the design or development of a digital product begins. It’s the vision of a solution that needs to be validated with real potential customers to prove that it’s desired in the marketplace. Although UX design encompasses numerous details such as visual design, content messaging and how easy it is for a user to accomplish a task, UX strategy is the “big picture.” It is the high-level plan to achieve one or more business goals under conditions of uncertainty.

The first edition also included an interview with another Adaptive Path founder, Peter Merholz. In it he said: “In an ideal world, you wouldn’t need UX strategy, because it would just be a component of your product or business strategy. We’re moving into this ideal world, I think. We’re seeing more and more often that UX is considered a part of a broader strategy. But, I think the separate and distinct concept of UX strategy was necessary for us — at least so we could focus on it — to shine a light on it and develop a toolkit to then wrap up in product strategy.”

Fast forward six years, and Merholz was mostly right. The UX strategy practice I described in my first edition is now synonymous with product strategy. Meanwhile, the term “UX strategy” is most frequently used to mean strategically executing UX at a particular organization or business unit: how the UX department should be run, how to assess and grow your team’s capabilities, how to broaden your UX team’s reach and influence and how to prioritize UX projects that can have the most return on investment (ROI).

So, Then What Is Product Strategy?

Traditional product strategy describes who your customers are, how your product fits into the current market and how it will achieve business goals. It starts with the product vision and ends with a roadmap on how to tactically get there. In an enterprise environment, a clear product strategy is crucial for aligning with stakeholders. It typically is led by a director of product, a product owner or product manager. The strategy process covers bringing a product to market and taking it through growth and maturity and eventually through decline.

But the discipline of product strategy has also evolved. It now places a stronger emphasis on satisfying the customer’s needs through user research and design practices. And the job titles are evolving along with it. UX designers now call themselves product designers. And I’ve watched many former UX strategists rebrand themselves as product strategists. Perhaps I will too.

Why Strategy for Digital Products Is Crucial

The purpose of any strategy is to create a game plan that looks at your current position and then helps you get to where you actually want to be. Your strategy should play to your strengths and be mindful of your weaknesses. It should rely on empirical, lightweight tactics that quickly move you and your team — because let’s face it, you’re probably not doing this alone — toward your desired destination. Strategy goes beyond the abstract nature of design and into the land of critical thinking. Critical thinking is disciplined thinking that is clear, rational, open-minded and informed by evidence. A valid strategy is the difference between success and failure. In the digital product world, chaos — time delays, increased costs and bad user experiences — get exacerbated when there is no shared product vision among team members.

A shared product vision means that your team and stakeholders have the same mental model for your future product. A mental model is the conceptual model in a person’s mind about how a thing works. For instance, when I was 10 years old, I believed the way my mom got cash was by going to a bank, signing a slip of paper and then receiving the funds from the teller. When I was 20, I believed I needed to take a bank card and key code to access an ATM to get cash. But if you were to ask my 16-year-old son how to get cash, he would tell you to go to the supermarket and ask for cash back when you pay for your groceries. The 2021 mental model for getting cash is very different from the 1976 mental model. That’s because new technologies and new business processes come together to offer a more efficient way for people to accomplish tasks.

Stale mental models are overturned. Life is disrupted for the better!

This is why I prefer to work with open-minded clients, whether they be startup founders or enterprise executives. Open-mindedness means that they are receptive to challenges and experimentation, and they understand that there is a chance their initial business idea might not be sustainable. If I see that a potential client is fixated on an idea and not open to the possibility of deviation, then they don’t need my help. My favorite clients are the ones who truly want to change a mental model and are open to experimenting their way to a successful outcome.

Even though envisioning innovative products is fun, it’s hard to get people to change their behavior. Customers have to see the value in the new way before they’ll consider abandoning the old. Devising new products to solve serious dilemmas is not for the faint of heart. You must be passionate and at least a little crazy to run headlong into all the obstacles that inevitably will get in the way.

Yet it’s the passion to solve a problem, change the world and make it an easier place to live in that makes for game-changing products. And this passion is not limited to entrepreneurs who quit their day jobs. It also emboldens people who have titles like product owner, UX/product designer or developer. These are people who are also passionate about using technology to conceive products that customers want. When you bring these types of people together, you have the necessary means to potentially make magic happen and destroy outdated mental models.

My goal in this book is to demystify the practice of UX strategy so that you can do just that. You’ll be able to immediately apply product strategy techniques to your projects in a variety of settings to keep you and your team from getting overwhelmed no matter what limitations you face. The techniques discussed in this book can be used for inventing a new product or revamping an existing product. An existing product is still susceptible to technological advances, new competitors and shifts in consumer expectations that could unexpectedly shorten its life cycle. As a product matures with a growing user base, it’s crucial to revisit your strategy. Thus, conducting validation experiments to discover new customer segments, marketing channels and revenue streams is a job that is never done.

I’ll show you how it can happen through a variety of case studies. I’ll even reach back into my family ancestry because I know I was inspired to be entrepreneurial from watching and learning from my family. You’ll see how the journey is the reward no matter if you’re a teacher, student or maker. You’ll also see that, no matter the project or the circumstances, producing inventive products is like being on a rollercoaster, and the only way to keep the product on the rails is to use an evidence-based approach for reducing uncertainties.

You can face uncertainty in one of two ways. You can take the safe route and avoid making any detours. Or you can choose a road less traveled and see where it goes. The first option might be more direct and is certainly easier. But for me, it’s far more alluring to blaze a new trail.

* * *

From the book UX Strategy, 2nd edition. Appears courtesy of O'Reilly Media, Inc. and will be published in March of 2021. Copyright 2021 Jaime Levy, all rights reserved. No portion of this text may be reproduced without written permission of the publisher and author.