Ten years after Napster launched, the music industry was in despair, with estimates suggesting there were forty illegal downloads for every legal download. Efforts to deter piracy were evidently doing more harm than good. The industry had spent a decade thinking it could force this problem to go away, but instead it just got bigger. Something had to give. At some point, the industry needed to let go of its old business model and grab hold of a new one, or, as The Economist suggested a decade earlier, “embrace the internet wholeheartedly.”

This is where the wider applicability of Tarzan Economics really comes into play as a framework for navigating us from moments of staring into the abyss to movements where you force disruption as opposed to having it forced upon you. As industry technologist Jim Griffin put it in 2009: “We cling to this vine that keeps us off the jungle floor. The trick is figuring out when to let go of that old vine and when to embrace that new vine.” The industry was desperate to hold on to its old vine yet not willing to swing to the new vine. It wasn’t yet ready to monetize the activity it was trying to criminalize.

Types of Goods and Digital Music

At the root of this was a lack of understanding of where the value lay in those pallets of music. There are countless examples of how we often struggle to define the nature of what we’re buying and selling. I proposed a surprisingly simple framework to help us do that, a framework that reveals the true nature of the goods being traded.

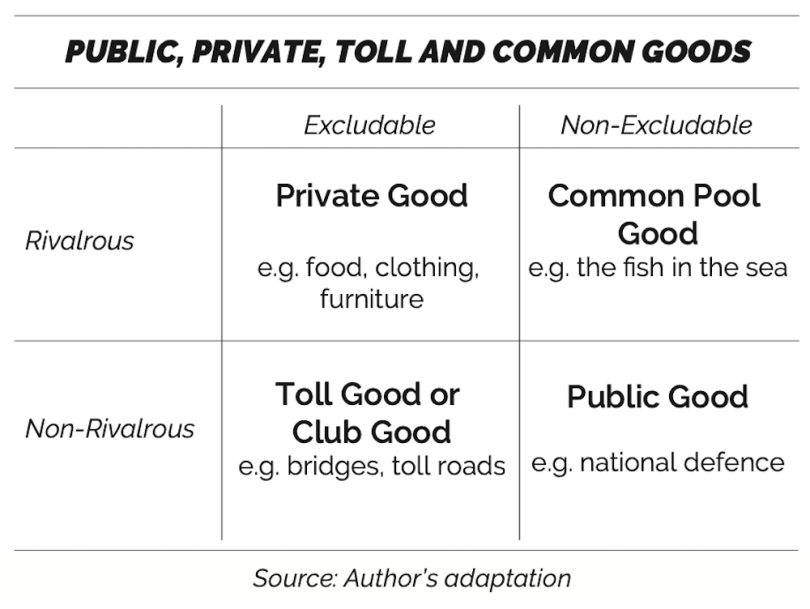

The framework focused on four different categories of goods — public, private, common and toll. A “private good” is one for which two conditions hold. First, the good is excludable. This means the owner of the good can deny others access (build a fence) or the law can build a legal fence by creating enforceable property rights in the good (criminalizing theft). Second, consumption of the good is what’s termed rivalrous (or scarce). That is, if I consume the good, you can’t, and vice versa. A meal in a restaurant is a private good — you can only access it in terms defined by the restaurant (so it’s excludable), and if I order the meal you can’t have it (so, it’s rivalrous).

A “public good,” by contrast, is non-excludable and nonrivalrous — national defense is a good example. If the nation is protected against foreign invaders, it is very difficult to exclude particular persons from the protection. And if I get the benefits of a strong national defense, it doesn’t interfere with you getting the same benefits. Government intervention is often justified in the name of providing a public good, as free markets often don’t work with these types of goods — if a good is non-excludable and non-scarce, then nobody will pay for it.

Although anti-piracy campaigns from the music and film industries have tried to link piracy with theft, intellectual property is not a pure private good. The law can create excludability for information goods, but information goods are not rivalrous. If I download an MP3 file it doesn’t affect your ability to do so and vice versa. How do we categorise goods like recorded music that satisfy enforceability but are not scarce?

Toll goods can extract value from consumers because the good creates value that can be captured by restricting access. A highway toll is a good example: it is both non-rivalrous (anyone can use it without diminishing others’ usage providing traffic is manageable) but excludable (access can be restricted).

You will have noticed we’re missing a corner of the matrix here — goods that are non-excludable, but still rivalrous. Those are “common pool goods.” The stock of fish in the ocean may be a common pool good, assuming it is either impossible or too costly to enforce fishing limits. Common pool goods are often referred to as the “tragedy of the commons” because unrestricted access to a resource such as fish stocks ultimately dooms the resource because of over-exploitation. This occurs because the benefits of exploitation accrue to individuals, while the costs of exploitation are distributed across all those exploiting the resource. Our current climate crisis is a very good example of this.*

*There is one footnote to the matrix – the “club good.” This is a good that has an optimal number of consumers. If too many consume the good, the joint value of the group will be reduced because of crowding effects. The term “club good” is used because the nature of most clubs is that members can share the benefits, but non-members can be excluded.

3 Inconvenient Truths

The matrix underlines the first of our three inconvenient truths that continue to challenge the media industries: Digital content is not rivalrous, and never will be, no matter how cheap an MP3 file may become. Copyright law gives me the authority to try to exclude you from making copies of my writings, but it does not make your use of the information — reading the words in this book — rivalrous.

The second inconvenient truth is just how “non-excludable” recorded music has become. As an illustration, it took three years to sell 1 billion tracks on iTunes, whereas BigChampagne estimated that during the same period around 1 billion tracks were being traded on P2P networks every month.

The third inconvenient truth was that the industry had unbundled itself by licensing the Apple iTunes model and allowing consumers to cherry-pick one or two tracks for 79 pence (or 99 cents) each as opposed to paying a whopping £7.99 ($9.99) for the album. The impact of this is well known, but what isn’t is that it was never supposed to happen. The original iTunes licensing agreement was supposed to be a controlled experiment within the niche Apple user base. When Steve Jobs stunned the market by putting iTunes on the mass-market Windows personal computers in October 2003, later describing it as “like giving a glass of ice water to somebody in hell,” labels realized unbundling had gone mainstream.

In adapting to digital distribution, the music industry faced this exact challenge: How do we extract revenue from rampant piracy on P2P networks when the files being traded are neither excludable nor rivalrous in consumption? As we’ve already discussed, the first decade of digital disruption saw the recording industry try to solve this problem by tightly gripping onto the old vine of their traditional business model, under the belief that they could create some form of excludability and scarcity in these new digital markets.

Let’s put the matrix to work to see how digital distribution changed the nature of music as a good in the market. Before digital platforms, the only two options for consumers were either paying for physical CDs or concert tickets, or attending free open performances that were limited by the venue’s attendance limits. Digital distribution opened up two nonrivalrous options – rights-managed legal downloads or MP3 files traded on P2P platforms.

This posed a problem for the music industry. For consumers, illegal P2P offered everything for free, as a non-excludable, non-rivalrous asset. Meanwhile, the legal route required paying for limited access to files with limited transferable value – a tough sales pitch for any marketing department!

Copyright and the Digital World

Let’s revisit the framework to show what happened to copyright when it lost the right to control copying:

The industry needed to somehow rescue music from public good status (where markets typically fail as no one needs to pay) and give up on the notion that it could ever return to a private good status (as scarcity had been lost forever). Rather than selling a physical product that qualified as a pure private good, they had to accept the need to reinvent the market and impose a toll on accessing content that would never again be scarce.

Spotify did just that and got the £7.99 ($9.99) bundle back by introducing an “option value” of what you could listen to, not what you did actually purchase. This moved the recording industry away from actual CD sales and towards a more actuarial model of option and risk where the bundle’s value was less about what you did with it and more about what you could do with it. The beauty of this simple framework remains as powerful today as it did back then; it showed not only an industry in which something had to give, but also that the market for its goods had changed irrevocably, and how it could reposition itself to deal with this disruption.

This is the biggest swing in the history of recorded music, and there’s much to learn from why — and particularly when — it happened. But in order to understand what Spotify and streaming accomplished, we need to understand a concept central to how the music business (and many other businesses) sees the world, a deeply flawed and rather silly-sounding acronym: ARPU.

Understanding ARPU and Its Shortcomings

ARPU stands for Average Revenue Per User. It is a simple valuation of how much income is generated by a company’s customers. In the case of the music industry, this would capture how much the average music-buyer spends each period on owning recorded music. It sounds simple but ARPU metrics can cause as many problems as they solve. For the music industry, one of the reasons why the first decade of digital disruption was so damaging was because of its failure to properly understand its own ARPU, and countless businesses and institutions have made the same mistake since.

At the core of the record industry’s fear of pivoting to digital music was the fear that digital distribution would cannibalize existing revenues from CD and download sales: the old vine of ownership may have been dying, but it still produced an ARPU that was preferable to what you could expect from the new vine of access. Why would you even contemplate letting go of what you had, when what you would need to cling on to instead would make you worse off?

The fear kicked in as initial attempts to launch legal alternatives to Napster failed — sites like Pressplay and Sony Connect (backed by a consortia of the major record labels) are still fondly remembered as the worst websites of all time. That fear was compounded by every subsequent failed attempt from the music labels to compete with the P2P sites. Measuring traditional ARPU wasn’t giving them the confidence they needed to make the leap.

A protective mindset had developed: retaining those remaining lucrative music buyers (who were sometimes referred to as “£50-a-month man”) was clearly more valuable than gambling on them being willing to spend £120 ($120) a year on an “all-you-can-eat” Spotify subscription instead. Critics of the “toll good” model of music streaming argued vehemently that letting go of their “private good” status meant turning music buyers into streamers was forcing record labels to swap analogue dollars for digital dimes.

At the heart of this fear was the definition of the consumer, or music buyer. The average spend of “£50-a-month man” may have looked higher than with a subscription model, but that was hiding an important fact: Although ARPU was high for those who were still purchasing music, the total number of people doing so was falling fast.

Access, Not Ownership

MusicWatch, a respected consultancy, has tracked developments in these key metrics for the United States across the two disruptive decades. (Note: A remarkably similar story exists for the U.K.) Their ARPU data over time illuminates just how stubbornly the music industry clung to its “old vine” of ownership.

Back in 1999, when Napster launched, over 170 million Americans bought CDs and the average spend per buyer was $63 per annum. Though individuals surely varied in how much they spent, what is striking is that the vast majority of those over-thirteen-year-olds bought something as opposed to nothing — they were ones, not zeros. In the ten years that followed, music moved from a private to a public good thanks to Napster and other P2P sites. When the labels started suing customers, inadvertently raising awareness of illegal P2P platforms, both reach and revenue collapsed. The share of Americans who bought music fell by over 40 percent to less than 100 million. Their average spend dropped to $52, 20 percent off its peak in 2000, and less than half that of the ARPU generated by a subscription model with an agreed price of $120 per year. The majority of the U.S. adult population was now giving record companies zero. Fears about cannibalization were increasingly misplaced; you cannot cannibalize zero.

(This fearing of cannibalization has an important precedent. In 1994, the Blockbuster chain began making SEGA games available for rental, much to the annoyance of the gaming giant’s sales teams. However, these fears were misplaced as sales went up soon afterward.)

When the majority of the population isn’t buying, you should optimize for reach rather than revenue. Growing your audience in a new market — converting the zeros to ones — is a better long-term strategy for scaling ARPU than trying to squeeze more revenue from a dwindling market of existing buyers. Now let go of those old bar charts and grab on to the new.

Paying for access rather than ownership really took off in July 2011 when Spotify launched in the United States. By the end of that year, MIDiA, another respected consultancy, estimated there were 4.5 million people paying an average of $75 per year to access all the world’s music instead of buying it. By 2019, that had ballooned to 93 million Americans paying an average annual retail price of $81 — 55 percent more than the same number of buyers were spending back in 2009.

The rising bars in the chart below illustrates how the industry reaped the reward from reaching out to the new vine.

The subscribers captured in this chart don’t show the whole picture, however. Accounting for what’s termed sub-account holders — members of a family plan — today there are over 110 million Americans enjoying the benefits of account holders paying for something that always has been and always will be voluntary to pay. In addition, there’s an array of advertising services such as YouTube that are free to the consumer and compensate the rights holder. Put these two formats together and you have an American music industry that’s grown at double-digit rates for the past four years — a feat many other media sectors can view only with envy.

***

Excerpted from Tarzan Economics: Eight Principles for Pivoting Through Disruption by Will Page. Copyright © 2021. Available from Little, Brown and Company, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.