When you actually launch new products to customers (which many teams don’t do), product managers and designers who’ve focused on scaling issues and optimization have to flex a new type of cross-functional muscle: how to work with product marketing. The default mode of this partnership across the industry is beyond terrible.

Product management works in isolation on product, then at the last minute hands things off to product marketing to name it and launch it. Product marketing then does their best to come up with a brand-forward approach to make the product or feature sexy to their customers, but more so for their portfolios or their friends. Marketing doesn’t match the product, dev teams are pissed that marketing doesn’t understand the feature, marketing is pissed they got brought in last minute, customers don’t know what the hell the thing the company released is and don’t use it. Rinse and repeat.

I have a real appreciation for great brand marketing, because I personally suck at it.

If you don’t want to do that at your company, you actually have to put in work to make sure the default mentioned above doesn’t happen, and for a company that isn’t in a rhythm of shipping new products and features over time, muscles can be poorly toned for that. Consider a workout training video that helps you understand how to tone those muscles and learn how to position products well so customers adopt and understand them.

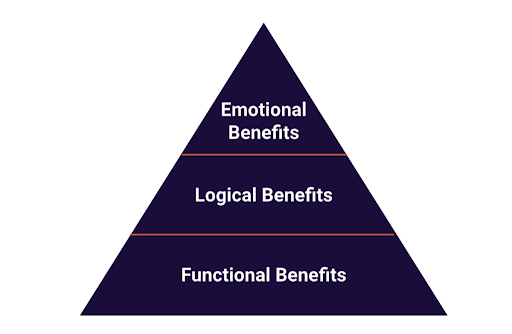

The Brand Marketing Pyramid

If you’ve ever had the pleasure/misfortune of getting an MBA, you’ve likely suffered through a few mostly worthless marketing classes. But they’re not all bad. Perhaps the most important concept you can learn from these classes is how positioning works. If you’re positioning any product or feature or service, there are three different layers of branding that need to occur, and they get harder to execute the closer you get to the top.

Branding for a Successful Product Launch

- Functional benefits: what the features deliver.

- Logical benefits: what the product enables you to do.

- Emotional benefits: how it makes you feel.

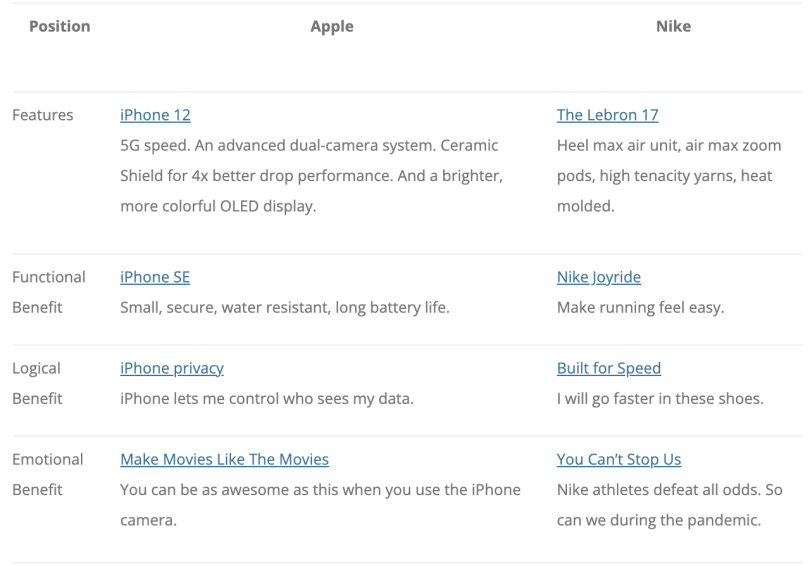

Most brands work their way up the pyramid over time. At first, they try to clearly describe what their product or service does, taking a list of features and translating them into benefits. As the brand learns more about what customers actually care about, they usually determine that focus isn’t as optimal as describing what the features actually enable — sometimes called “the job to be done.” Describing a phone as having “10 megapixels” (feature) means very little to most people, and even saying “higher resolution” (functional benefit) is often not as impactful as saying “it takes great pictures” (logical benefit), but it depends on the audience.

If a brand gets really good at describing the functional and logical benefits, over time it tries to reach the customer with more emotional resonance: “Feel like a professional photographer” (which was basically the “Shot on iPhone” campaign). But Apple is able to do this because it’s built up high awareness of its features and functional benefits over time.

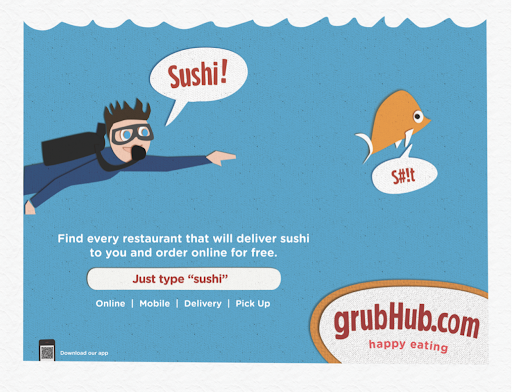

Let’s take a look at how this evolved at Grubhub while I was there. When I joined the company, our tagline was “discover who delivers” — clearly what the company did. When we hired our head of marketing, we overhauled the brand and changed the tagline to “eating made easy” — more of the logical benefit. Eventually, we moved up the pyramid again to “happy eating,” an emotional benefit.

Once it all came together, Grubhub had a playful, visual style that resonated with young professionals, advertising that focused around the irrationality of hunger, and a nice mixture of emotional resonance, features, logical and functional benefits in its advertising.

While Grubhub got better at this type of work over time (and has gotten so much worse since that head of marketing left), Nike and Apple are fantastic at this balance. While they receive accolades for their work at the top of the pyramid, they still do all the forms of positioning in different contexts.

Positioning Features Is Harder Than Positioning Products

I have a real appreciation for great brand marketing, because I personally suck at it. Ultimately, what great positioning does is provide potential customers a promise of the product experience. If branding obfuscates that, it’s not doing its job. This is why when many brands go for the emotional benefit without pairing it with the other elements of the pyramid, it doesn’t work. But the reason brands try to do this in the first place is there is a lot of value to be gained by pushing what the product can be considered for over time, and creating loyalty through emotional connection in the process. That’s hard though!

Product people tend to suck at positioning themselves. We’re often too wrapped in our jargon to speak in ways the customer understands.

Positioning part of a product is even harder than normal positioning because the promise of the feature has to sit inside the broader context of the positioning for the overall product. Comprehension of how products work and what they can do is already incredibly difficult, so adding new elements to products compounds problems most products are already not good at.

Product people tend to suck at positioning themselves. We’re often too wrapped in our jargon to speak in ways the customer understands. So we’re happy to have marketing take the lead. But the default mode of positioning features from marketing teams is to try to infuse the brand into them without understanding how that practice can create even more comprehension issues.

Scott Belsky, the chief product officer at Adobe, talks about how his startup initially got this wrong, and how it hurt comprehension (the whole post is great, but the example is in the “be more accommodating” section).

We faced this same issue when I was at Pinterest. When we launched the product internationally, retention was a lot lower than in the U.S. As we watched international users try the product, we realized that many were struggling with the key call to action saying “Pin it!,” which didn’t mean anything in their language. The product team wanted to change it to the local word for “Save,” but the brand marketing team was absolutely against it. We tried it anyway, and saw a 15 percent increase in activation rate, even in the U.S.! Our own brand was confusing users, the exact opposite of what it is supposed to do. We faced a similar issue from an SEO perspective.

Our images were called “Pins.” By changing our title tags to say “images” instead of “Pins,” we received 5 percent more traffic from Google. There is plenty of time to get activated users to build an emotional connection with our brand, but if our brand makes the product not enticing to try or too confusing, it needs to back away until a later time when it can help, not hurt, company goals.

Many times product and marketing teams will try to “go their own way” to solve the problem. Product creates a page for SEO. Marketing creates a page for the launch that is more branded. Not a good idea. The buzz the marketing team can create with that landing page will help with SEO goals because it can drive links that help Google trust the page more to rank it higher.

Instead, product and marketing must work together to carefully balance positioning to maximize what helps the page rank, what gets potential customers interested and what drives loyalty over time. This is what the best brands like Apple and Nike do.

Product Positioning Is a Delicate Dance

Many times when we talk about product marketing, we talk about the launch. But positioning is where the real long-term value is for features and new products. Dev and marketing teams have a lot of different variables to balance in launching new products and features, and positioning is at the heart of many of them and the hardest to get right. In almost all cases, we will need to iterate to optimize comprehension, adoption, retention, satisfaction and that emotional connection that leads to word of mouth and improved adoption of things teams will launch in the future.

* * *

This was adapted from an internal blog post in collaboration with Tamara Mendelsohn, Eventbrite’s CMO. It’s been slightly edited to make more sense for people outside of Eventbrite and republished on my blog, Casey Accidental. Thanks to Tamara Mendelsohn for contributing to this essay.