The pigeonhole principle is a simple, yet beautiful and useful mathematical theory. Given a set A of pigeons and a set B of pigeonholes, if all the pigeons fly into a pigeonhole and there are more pigeons than holes, then one of the pigeonholes has to contain more than one pigeon.

Pigeonhole Principle Definition

The pigeonhole principle states that if n items are put into m containers, with n > m, then at least one container must contain more than one item.

What Is the Pigeonhole Principle?

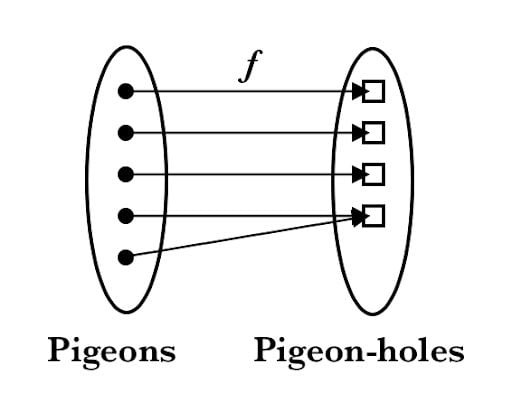

Think of the pigeonhole principle as the statement about a function f from domain P → PH, where pigeon n flies into pigeonhole f(n), as is shown below:

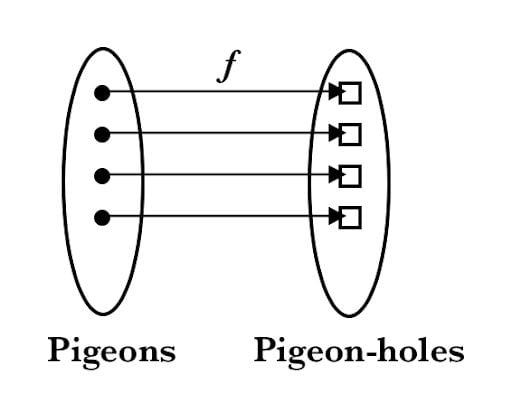

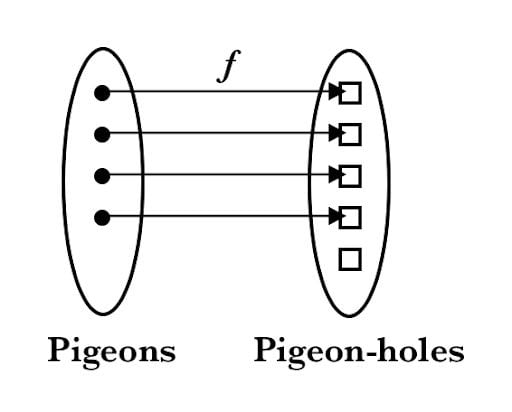

The three cases illustrate three types of functions from a domain (“pigeons”) to a co-domain “pigeonholes,” which can be mapped to one another:

- Case A: If

|n| > |f(n)|, then the function is a non-injective surjective function, not a bijection. - Case B: If

|n|= |f(n)|, then the function is a injective surjective function, bijection. - Case C: If

|n| < |f(n)|, then the function is an injective non-surjective function, not a bijection.

Case A is the case illustrating the essence of the pigeonhole principle, namely that if you put n items into m containers and n > m, then at least one container must contain more than one item. The function f that maps pigeons into pigeonholes is hence called in mathematical terms a surjective function. We may prove the principle easily by contradiction.

Pigeonhole Principle Proof

Suppose that the total number of pigeons n are to be put in m number of pigeonholes and n > m. Assume that there are no pigeonholes with at least n/m pigeons, i.e. that each pigeonhole has less than n/m pigeons:

- Number of pigeons in each pigeonhole

< n/m - Number of pigeons

< m × n/m - Number of pigeons

< n

But given that the number of pigeons is strictly equal to n, we have obtained a contradiction to our assumption that each pigeonhole has less than n/m pigeons.

Who Invented the Pigeonhole Principle?

The first formalization of the pigeonhole concept is believed to have been made by Dirichlet in the 1800s as what he called Schubfachprinzip or the “drawer/shelf principle.” The first appearance of the term “pigeonhole principle” was used by mathematician Raphael M. Robinson in 1940.

Pigeonhole Principle Examples

While the pigeonhole principle is a simple and easily graspable statistical concept, it’s also powerful enough to prove truths that are far from obvious. In a sense, one of the quintessential counting arguments, the pigeonhole principle for instance allows us to prove statements such as:

- At any given time, there live at least two people in California with the same number of hairs on their heads.

- You cannot cover a 8 x 8 square chess board with two diagonally opposite corners removed, with domino pieces of size 1 x 2.

- In a room full of 367 people there are at least two people with the same birthday.

- Any lossless compression algorithm that makes some inputs smaller will also make some outputs larger.

Let’s look at how it can help us prove statements that sometimes seem unknowable.

Common Properties in Large Groups

At any given time there live at least two people in California with the same number of hairs on their heads.

To prove this, we need to establish two facts:

- That the population of California is larger than 20 million, it’s actually more like 40 million.

- That it’s a biological fact that every human head has fewer than one million hairs. Typically, the number ranges between 90,000–150,000.

We can find the proof for this example in the Book of Proof, by mathematician Richard Hammack.

Proof of Example A (Hammack, 2013 pp. 207)

Let A be the set of all Californian heads and B = {0,1,2,3,4, ..., 1000000} be the number of hairs one can have on ones' head. Let f be a function that maps A → B, for which f(x) equals the number of hairs on the head of x. Since |A|>|B|, the pigeonhole principle asserts that f is not injective. Thus there are two Californians x and y for whom f(x) = f(y), meaning they have the same number of hairs on their heads.

Subset Cardinalities

If A is any set of 10 integers between 1 and 100, then there must exist two different subsets X and Y for which the sum of elements in X equals the sum of the elements in Y.

Consider for instance the random set A = {6, 7, 11, 12, 17, 50, 51, 80, 90, 100}, which has subsets X = {7, 12, 17, 50} and Y = {6, 80} for which the sum of the elements in X equals the sum of those in Y, namely 86. If we try to mess this up by changing a value in A, like changing the seven to a five, we would instead get A’ = {5, 6, 11, 12, 17, 50, 51, 80, 90, 100}, and yet still find subsets W = {6, 12, 17, 50} and Z = {5, 80} whose cardinalities are both equal to 85.

We can also find this proven in the Book of Proof.

Proof of Example A (Hammack, 2013 pp. 206)

Suppose A ⊆ {1, 2, 3, 4, ..., 99, 100} and |A| = 10. Notice that if X ⊆ A, the X has no more than 10 elements, each between 1 and 100. Therefore, the sum of all the elements of X is less than 100 × 10 = 1000. Consider the function f: 𝓟(A) → {0,1,2,3,4,...,1000} where f(X) is the sum of the elements in X.

As the cardinality of |𝓟(A)| = 2¹⁰ = 1024 > 1001 = |{0,1,2,3,...,1000}| it follows from the pigeonhole principle that f is not injective, i.e. that it is a "many-to-one" function.

Therefore, there are two unequal sets X, Y ∈ 𝓟(A) for which f(X) = f(Y). Stated differently, there are subsets X ⊆ A and Y ⊆ A for which the sum of elements in X equals the sum of elements in Y.

The Chinese Remainder Theorem

The well-known Chinese remainder theorem gives the necessary conditions for multiple equations to have a simultaneous integer solution. It may be stated as:

Let m and n be relatively prime positive integers. Then the system x = a (mod m), x = b (mod n) has a solution.

The Chinese remainder theorem is useful because it establishes that if we know the remainders of the division of an integer n by several integers, then we can uniquely determine the remainder of the division of n by the product of these integers. The theorem was famously first stated as early as the third century by Chinese mathematician Sunzi Suanjing:

“There are certain things whose number is unknown. If we count them by threes, we have two left over; by fives, we have three left over; and by sevens, two are left over. How many things are there?”

To illustrate this practically, think of a box of gold coins. We know that if the coins are equally divided among six friends, four coins are left over. If the coins are equally divided among five friends, three coins are left over. If the box holds the smallest number of coins that meets these conditions, how many coins are left when equally divided among seven friends? The answer is zero.

Proof of Example C

First consider the sequence

(1) b, b + m, b + 2m, ..., b + (n - 1)m

The sequence forms a complete residue class, modulo n. To see this, consider the sequence:

(2) 0, m, 2m, 3m, ..., (n - 1)m

Since the greatest common divisor of (m,n) = 1, we have xm ≡ ym (mod n) <=> x ≡ y (mod n). Hence, each element in the sequence (2) is unique. Adding b to the sequence (1) only cyclically permutes the residue class.

By the pigeonhole principle, for any 0 ≤ a < n, we must have b + km ≡ a (mod n) for any k ∈ {0,...,n − 1}.

Constructive vs. Non-Constructive Proofs for the Pigeonhole Principle

Finally, a note about the type of proofs pigeonhole proofs belong to. Although useful, a defining characteristic of pigeonhole proofs is that they are non-constructive. This means that although they prove the existence of something, they fail to provide an explicit example that proves the theorem. To illustrate the difference, consider two proofs of the same statement, namely that:

There exist irrational numbers x, y for which xʸ is rationalLet’s consider a non-constructive proof, as found in Hammack’s Book of Proof on page 128, which shows that there exist irrational numbers x and y for which xʸ is rational without actually producing an example.

Non-Constructive Proof

Let x = √2^(√2) and y = √2. We know y is irrational, but we do not know whether x is rational or irrational. If x is irrational, then we have an irrational number to an irrational power that is rational:

xʸ = (√2^(√2))^(√2) = (√2)^(√2 × √2) = (√2)² = 2

If x is rational, then

yʸ = √2^(√2) = x is rational.

Either way, we have an irrational number to an irrational power that is rational.Next, consider an alternative, constructive proof.

Constructive Proof

Let x = √2 and y = log(9). Then

xʸ = √2^(log(9)) = √2^(log(3²)) = √2^(2log(3)) = (√2^2)^(log(3))^= 2^(log3) = 3

As 3 is rational, we have shown that xʸ = 3 is rational.

We know that x = √2 is irrational. We do not know whether y = log(9) is irrational. Suppose log(9) is rational, so that there are two integers a, b for which a/b = log(9). Then 2^(a/b) = 9, so 2^(a/b)ᵇ = 9ᵇ, which reduces to 2ᵃ = 9ᵇ. However, we know that 2ᵃ is even and 9ᵇ must be odd, so they cannot equal one another. We have obtained a contradiction and must assume that log(9) is irrational.In the process of constructing the proof, we also provide an example of a case where the statement is true, namely for x = √2 and y = log(9). This, one never obtains from pigeonhole, and other non-constructive proofs alone.