In the early 2000s, it was pretty much impossible to coordinate an online game with your friends and chat together while playing. Most people still didn’t own a cell phone, and home phone lines were often tied up with modems. Trying to run an instant messaging program alongside a game didn’t work well either.

Chris Kirmse, an engineer in Yahoo’s games division in the late ’90s and early 2000s, was annoyed by this. He wanted an easy way to see when his brother was online so that he could join his game and talk with him.

So he built one. First for Yahoo, and then later, as a standalone product at a company called Xfire.

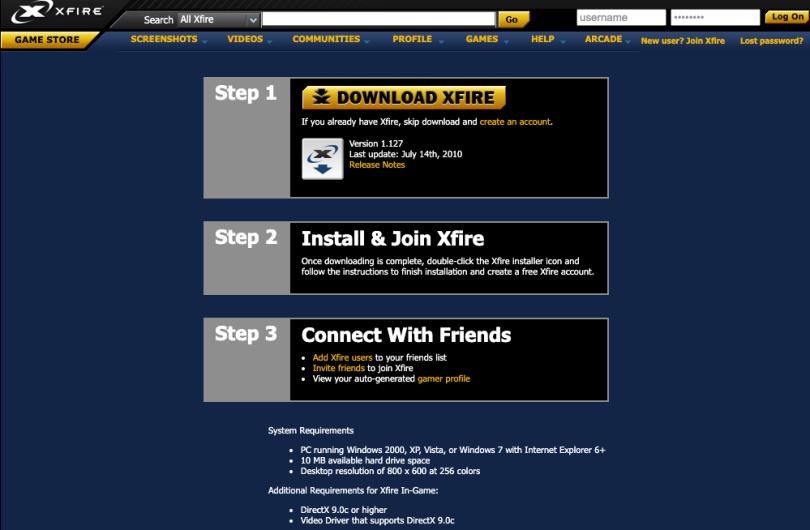

Xfire kept track of where and when gamers played online, and allowed them to instant message each other in game. It also pioneered and popularized many features that are ubiquitous in gaming platforms today, like stat tracking, screenshot capture, in-game voice chat, peer-to-peer file sharing and live streaming. Xfire grew a hardcore fan base of tens of millions of users, and eventually got acquired in a nine-figure deal. It was a genuine Silicon Valley success story.

Until it wasn’t.

In 2015, Xfire shut its messaging services down for good. Here’s what happened.

Responses have been edited for length and clarity.

Part I: ‘So We Just Did It’

While at Yahoo, Kirmse and Brian Gottlieb developed a computer system where someone could see what game server their friend was playing on and then use Yahoo Messenger to join. Eventually, Kirmse left Yahoo, and in 2003 joined the company Ultimate Arena, which facilitated a tournament-style gaming site where players could bet money against each other.

Chris Kirmse (VP of engineering): A month after I started at Ultimate Arena, we were in a meeting, looking at the numbers. It was not going to work. We needed something new.

Mike Cassidy (Ultimate Arena/Xfire CEO, 2003-2007): We got some useful feedback in exit interviews with customers. A lot of times they’d say, “I didn’t really like losing money, but I really liked your product, because it made it easy to play on the same game server as my friend.”

Kirmse: Lots of people wanted to play online games, and they wanted to keep talking to their friends while in game. There were just no good solutions for that need.

Cassidy: Chris also had been thinking about this.

Kirmse: I thought back to that idea I had at Yahoo. What if, instead of requiring an SDK, we did some sort of hack around the problems of the Yahoo Messenger system that we had made a few years earlier? At two in the morning, I sent an email to one of the developers. The next day, he was like, “Yeah, we can do that with an LSP.” Within about a week, we convinced the rest of the company that this was a good idea. (Garrett Blythe and I ended up getting a patent on that concept. He, Michael Judge and I built the prototype.)

Cassidy: For the most part, the team members of Ultimate Arena were happy to make the transition and go in a new direction.

Kirmse: So we just did it. We launched Xfire in the middle of January of 2004.

Dennis Fong (co-founder, speaking to Wired): We actually launched as a beta product to 100 gamers. We just said, “Hey, check this out, let us know what you think” and literally it just kind of blew up.

Dennis “Thresh” Fong was a retired professional gamer, well known for playing Doom and Quake. In 2007, he launched an Xfire competitor called Raptr.

Cassidy: Dennis was a great addition for the team when we were raising money. In the very early days, once you got to a thousand users, you just turned the clock and in a few months you’d have a million. But how do you get to one thousand? Dennis was very helpful there. He knew half of the top-100 gamers in the world. It was kind of a trickle-down effect, like many consumer products.

“It was not pretty. But it was functional.”

Kirmse: We had gone super fast to get something out there. It was really buggy. You had to reboot after you installed it. The servers were crashing sometimes.

Cassidy: I’m sure you’ve heard Reid Hoffman’s famous saying about how, if you’re not embarrassed by your product when you launch it, you waited too long. I don’t know if you’ve seen some of the screenshots from the early version of Xfire. It was not pretty. But it was functional.

Kirmse: Despite the problems, it was growing like crazy, immediately. By August of 2004, I think we had about 10,000 simultaneous users and a million registered users. We were off to the races.

Part II: ‘They Just Wanted to Slow Us Down’

In 2005, Yahoo filed suit against Xfire, saying the company had infringed its patent for a game server that talked to an instant messenger server. The matter was eventually settled out of court.

Kirmse: Yahoo bought a company called The All-Seeing Eye, which had a game server browser. They saw that Xfire was growing super fast, and that The All-Seeing Eye wasn’t. They just wanted to slow us down, so they sued us, saying we infringed their patent. Their patent being my patent. I knew we weren’t infringing the patent because I worked with a lawyer to write it.

Cassidy: Sophisticated investors are familiar with lawsuits as a business tactic used by one organization against another. And they’ll do some due diligence and look into the merits. Some investors will say, “We think, in the end, the case will get dismissed or they’ll settle for some modest amount, or you’ll win.” Which is what happened. We found investors who said, “Yeah, we think the case against you is not valid.”

Kirmse: It was a case of a big company trying to squash a little company. We ended up having to settle with Yahoo for not very much, just to make it go away at the end.

Yahoo declined to comment for this story.

Part III: ‘The Next Myspace’

By 2006, Xfire had more than four million users. An article in Fortune magazine from February of that year declared, “this tiny San Francisco company could be the next MySpace, or more relevantly, IGN.”

Kirmse: We kept innovating on the product, adding great features that people loved. We had one of the first in-game overlays. We added screenshot capturing, voice chat, video capturing and live streaming. We tracked game hours from the beginning; that was an incredibly popular feature (now all the consoles and Steam do it, but I think we were the first, and it was essentially an afterthought).

Cassidy: We read the forums. We did surveys where we’d ask what features people are most interested in. We also got direct emails from people who had feature requests. We would have a weekly product feature prioritization meeting. It was kind of a fun, contentious meeting. We’d sit down and arm wrestle over what the new feature would be.

“Even though there were a lot of clones and copycats, no one else was able to come close to us.”

Kirmse: We were one of the first Windows apps that had mandatory updates. It’s super common now, but the concept of forcing new native code onto people’s machines every two weeks was brand new. It put a lot of pressure on us and the QA team. We did 127 releases between January of 2004 and August of 2010. That in-game technology was incredibly difficult and challenging.

Cassidy: The biggest input — and a lot of this was Chris Kirmse — was to just listen to what people requested, and add that feature. It’s almost a tautology, but when you do that, people really like your product. Over time, the product kept getting better and better.

Kirmse: Even though there were a lot of clones and copycats, no one else was able to come close to us during that time.

Part IV: ‘It Was Very Exciting’

In 2006, Xfire was acquired by Viacom’s MTV Networks for $102 million. Most of the original Xfire team left shortly after the acquisition. Xfire remained a Viacom asset from 2006 to 2010.

Kirmse: We had been working so hard for a couple of years. When you’re doing mandatory updates every two or three weeks of native code, there are a lot of late nights. So when the acquisition came through, it was very exciting.

Cassidy: The goal had been to leverage each other’s properties. MTV had tons of users — could they expose them to Xfire?

Kirmse: We were bought as part of a strategy of rolling up a bunch of game community companies. We didn’t really know what was going to happen next. What ended up happening next was basically nothing all that great.

Scott Wilson (network operations engineer, via email): For many years after Viacom purchased Xfire, they seemed to have issues finding where to fit us within their company culture and figure out how to use Xfire for branding.

Cassidy: Inside Viacom, there were different groups. There was MTV, VH1, Comedy Central, Spike TV, a couple other ones. We needed to be in one of those groups, and it wasn’t clear which group. The monetization part was not smooth sailing, either.

“What ended up happening next was basically nothing all that great.”

Kirmse: Viacom didn’t give us much in the way of resources, because, within a few months, the person who had driven that gaming community company acquisition strategy was fired. All of those game companies were essentially abandoned inside Viacom. Within a year or two, pretty much everyone left Xfire, except for the product development team.

Cassidy: In the end, I missed the startup environment. I stayed for a year and then said, “OK, I’m gonna do my next adventure.” But it was fun.

Wilson: After a year or two, things began to change.

Kirmse: All of us ended up getting squeezed for resources.

Wilson: Viacom imposed huge goals of revenue generation on us, which we could not meet, no matter what we did.

Kirmse: We were just trying to build a great product for gamers. Because we were all gamers, and we knew what we wanted.

Wilson: One day, we were all told that Xfire was going to be offered up for sale. Within a week, someone from a huge gaming company showed up and began interviewing us. That process was a little nerve-racking, but there was one thing that was certain — they had a plan, and that excited us. But the deal fell through. A few weeks later, I went to lunch and came back to the office. Everyone was packing up their desks, taking their boxes to their cars. I was told that HR was looking for me. I rushed in and met with HR, and I learned that everyone was being let go, with the exception of four people. I was one of those four people. We were to go to a hotel and meet the new owners of Xfire, Titan Gaming.

Kirmse: The day that deal closed, I had to lay off almost everyone, including myself.

Part V: ‘We Needed to Rebuild From Scratch’

In 2010, Xfire was purchased by Titan Gaming. Growth had slowed and competition with Steam heated up, so the company tried to pivot to a tournament platform for casual-competitive gamers.

Mark Donovan (co-founder, Titan Gaming; Xfire CEO, 2013-2015): Xfire’s challenge was its growth had started to plateau and then decline slightly, and there were a lot of competitors in the market. Steam basically just started to swallow the universe of gaming. Over time, it became less and less relevant for users to have this other chat application when Steam did a lot of those things and also was where people bought games. It became a product challenge to keep Xfire relevant. And so we tried to figure out different ways we could do that.

Wilson: The direction of the company changed drastically. They wanted to revamp the website, stop supporting new games and change the client to be more of a tool to set up tournaments among players. Titan Gaming wanted to go back to something like what Ultimate Arena had been.

“We could take this tech and turn it into an early e-sports platform.”

Nile Plante (director of product management, joined in 2011): We needed to figure out a way to retool the business and the product and, at the same time, figure out what we could salvage from this technology. (It was really hard to work with the codebase; making simple changes seemed to take weeks or months. So it was really about trying to figure out what we could keep from the codebase and what we needed to rebuild from scratch.) We realized there was a budding e-sports thing, and so we decided we could take this tech and turn that into an early e-sports platform.

In 2011, Xfire raised an additional $4 million and began operating independently from Titan Gaming. Soon, new management was brought in. Strategy shifted.

Plante: We took on a lot of investment. And some investors wanted to move to China, so they switched out leadership and hired a CEO who moved us into China.

Donovan: We had an opportunity to grow the company in Asia. That was an opportunity that the board brought, and they wanted Malcolm to come in because he had experience in Asia.

Malcolm CasSelle (Xfire CEO, 2012-2013): PC gaming in China was going crazy, and I had a lot of China experience. I struck a deal that would get us into the internet cafes, which is where all the gaming happens there. And then we were trying to figure out how to localize this thing to China. And I raised the money for us to do that, and we started to pursue it.

Plante: That turned out to be a big distraction for about two years.

CasSelle: We probably needed another six to nine months of runway to really prove it out. We had a group of investors who clashed with the existing management and shareholders, which prevented the company from moving forward.

Plante: We had a lot of management changes. How we were reacting and how we positioned ourselves depended on the CEO and what their vision was. It ranged everywhere from, “We’re going to go to China” to the tournament platform idea.

Donovan: My focus moved to the tournament product. What we tried to do was basically build out an infrastructure to allow game publishers to integrate casual-competitive tournaments and leagues directly piped into the back-end of their games.

Plante: We went on to build the tournament platform, which we launched in a beta in 2014.

Part VII: ‘We Would Have Ended up a Blend of Twitch and Discord’

The Xfire client and social site were sunset in 2015. That same year, Discord, a free instant messaging service popular with gamers, made its first release. Today, Discord has over 100 million active users. Steam has over 90 million. Twitch averages over 17 million daily visitors.

Plante: I think the legacy of Xfire is the combination of Steam, Discord, Twitch — all these things that were once under one umbrella, expanding out into their own spaces. A lot of the things that were pioneered at Xfire exist in a lot of places, and in many respects they’ve been commoditized.

Donovan: It could have been Steam. It could have been a distribution platform. It could have been the center of the universe for PC gaming. I think they sold too quickly, and to a media company that didn’t understand technology.

Kirmse: I don’t know what would have happened. I suspect we would have moved more in the direction of content, and would have ended up being like a blend of Twitch and Discord. I remember saying to someone a few years ago when I first saw Discord, this is the kind of thing we would have at Xfire if we were still around now. They approach users and product development just like we did. They were gamers creating products for gamers, with innovative technology and great product marketing around it.

Cassidy: Sure, if we had more patience, and dug in and said, “We’re going to make this into a 10-year, 20-year company,” yeah, I mean, we could have easily been a game distribution platform, we could have had the kind of depth and breadth that Discord has.

In June of 2020, Discord rebranded, positioning itself not as a tool specifically for gamers but as an all-in-one communication platform for “anyone who likes to talk.”

Built In asked Kirmse if he thinks Xfire would have eventually pivoted to appeal to a general audience.

Kirmse: We were always going to stay focused on gamers, because everyone in the company was a gamer. We didn’t know how to do anything else. That doesn’t mean we would have been successful at it. I’m just saying it’s what we would have done.

Today, Xfire.com is a directory for online casinos.