On New Year’s Eve, my siblings and I wanted to do something fun with our parents. We couldn’t agree on what movie to watch, and a card game for that many people didn’t seem feasible. So I proposed we play The Jackbox Party Pack.

My suggestion was met with blank stares.

For the uninitiated: The Jackbox Party Pack is a bundle of virtual parlor games. Each player’s phone acts as a controller, with shared information displayed on a screen everyone can see. Cheeky voiceover narration and zany animations guide players through games, which involve trivia questions, word guessing and picture drawing. When you play a Jackbox game, winning is secondary; the true objective is to get the group to laugh.

Eventually, my family agreed to give the game a shot. Within a half hour, we were all smiling and laughing. Even my parents.

In the wake of pandemic lockdown, the popularity of Jackbox Games has reached new heights.

The Jackbox Party Pack series has been enjoying a steady six-year run. But in the wake of pandemic lockdown — and the resulting uptick of social gaming — its popularity has reached new heights. Traffic to the games’ servers is surging. Celebrities are streaming themselves playing.

The mass-market accessibility of Jackbox is there by design. The Jackbox Games studio crafted a tried-and-true game-design formula — it relies on a playbook, called “The Jack Principles,” outlining its design philosophy — and stripped down its games to have as little friction as possible, lowering the barrier to entry so that even my septuagenarian parents can enjoy them.

The Phone as Controller

The immediate differentiator between Jackbox and other games is the form factor: Players gather around a main screen, and each uses their personal smartphone as a controller. They punch in a shared room code on a web page and are immediately connected. There’s no additional app for each player to download, no gaming peripherals required.

The phone-as-controller set-up limits what Jackbox can do in some respects (you can’t feasibly cram a dozen buttons and replicate a joystick on an iPhone). But there are some creative mechanisms that the constrictions help to unlock. For example: The game can send each player’s phone unique information that only they can see.

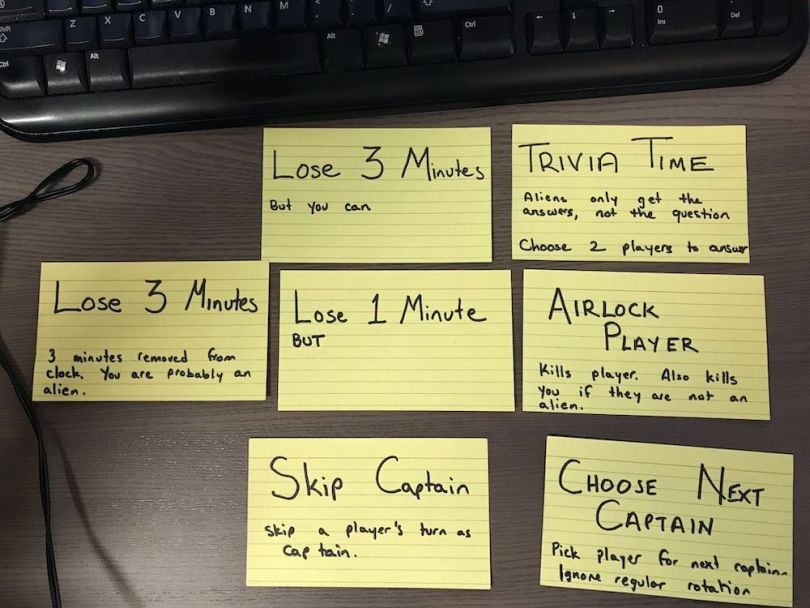

In the game Push the Button, two random players are assigned to be aliens disguised as astronauts. Their job is to sabotage the crew and survive. The remaining players are astronauts, and they’re tasked with exposing the identities of the moles before time runs out.

The game asks players inhabiting the two roles to answer a slightly different set of personal questions via phone. Then, everyone’s answers are broadcast on the shared screen, and based on the apparent strangeness of answers, people try to figure out who’s an alien. This inevitably leads to finger pointing and social deduction. And it only works because specific instructions can be sent privately to different players’ devices.

“You can’t do that on the PlayStation controller, because you can’t assign player roles like that,” Chase McClure, senior software engineer at Jackbox Games, told me. “That’s just the kind of game that only works on a phone.”

McClure, whose background is in UX, was hired by Jackbox Games in 2019 to be an “advocate” for the phone. He said the studio has found a go-to formula for everything the phone-as-controller can accomplish without overwhelming the user.

First, the Jackbox phone controller has a limited pool of components — the user can draw, choose between a collection of buttons, or input text.

“We try to keep it pretty simple,” McClure said.

“We try to keep it pretty simple.”

Limiting the number of ways in which players can interact helps them get the hang of the games pretty quickly. Once the user plays a few, they have essentially learned how to play all of them — even if the plot, animation and tone of each new game feels different.

McClure added that the studio still likes to consider new ways in which it might be able to advance the controller’s capabilities even further.

“We have a ton of ideas on if we could use motion controls, like if we could use the [phone’s] gyroscope, or if we could use the camera,” he said.

Ultimately, he said, Jackbox Games doesn’t want to alienate players who don’t have the latest and greatest smartphones. Their aim is to create games that just about anyone with a phone and an internet connection can experience.

How to Make a Game Fun and Easy

Since its early days, the Jackbox Games studio wanted its games to have the broad appeal of Seinfeld.

“That means keeping the interface really simplified,” Allard Laban, Jackbox’s chief creative officer, told me. “If I find it difficult, then, you know, my aunt’s going to find it very difficult, so let’s get it at least dumb enough for me to understand so I can actually interact with it.”

To keep things streamlined, the team’s designers take guidance from “The Jack Principles”: a document written by Harry Gottlieb, the company’s founder. The secret sauce, according to the document, is the creation of an “Interactive Conversation Interface” — meaning, basically, that designers should generate the feeling that there’s a real-life host talking to the players, pulling them along. This is what Jackbox Games aim for.

They achieve that vision by heeding three overarching principles:

- Maintain pacing — limit the user’s choices, give them one task at a time, make sure they always know what to do next, make them aware that the program is waiting for them, make their inputs as efficient as possible.

- Create the illusion of awareness — respond to the user’s specific choices with human intelligence and emotion.

- Maintain the illusion of awareness — use dialogue to convey intimacy, and have the game act appropriately based on what users are doing.

“We’re pretty well steeped in these principles,” Laban said.

He said the key to designing intuitive games is simple interactivity: The games never ask players to make multiple choices in a given moment; it’s always either pick an answer, draw a picture, or enter a word or phrase.

“We pace that out as part of the gameplay,” Laban said. “The games are kind of constructed in a way where we pull you along, and you’ve got something to do, and we will react to it, but it’s not [a stressful experience] where you’re juggling a lot of different things at the same time.”

The game Quiplash, for example, begins by giving each player two prompts on their phone to which they’re supposed to provide a funny answer. Then, players who received the same prompts are pitted against each other, with the remaining players voting for their favorites. In the final round, every player is given the same prompt, and everybody votes for their top three. The player who ends with the most points wins.

The game sounds awfully plain when explained in clinical terms like this, but in practice, it’s a ton of fun.

“We’ve developed this as one product, and we’re constantly burnishing new facets on it.”

There’s another component to the party pack’s design: While the game experience is immersive, it isn’t actually all that interactive (compared to the average video game, at least). That’s why a person who’s never played a video game, but grew up watching television, can still pick up Jackbox pretty quickly. The games draw on the language of TV — elements like narrative timing, transitions and dialogue.

Laban explained this to me: “When you’re playing a game with your 70-year-old parents, they’re tuned in because we’re speaking media language to that. We’re kind of doing timing and pacing that they might expect from a TV show. But they have a small amount of interaction, and they’re like, ‘Oh, I have to do something now because the man on the TV wants me to do something,’” he said. “It’s kind of this weird hybrid of passive and active media.”

Early successful Jackbox games gave the studio a blueprint for what structures resonate with users. For the most part, new Jackbox games are extensions, remixes or inversions of the studio’s earlier games. Drawful is Fibbage but with drawing. Joke Boat is an evolved Quiplash. Push the Button is Fakin’ It with a few added twists. The thing is, though, these similarities don’t really register at a conscious level.

“It all comes down to: It’s a Jackbox-type game,” Laban said. “I always think of the technology that we’ve developed for this [as] one product, and we’re constantly burnishing new facets on it.”

Testing, Playing, Iterating

At any given point in time, Jackbox Games has a backlog of about 50 game concepts to choose from. The team talks and argues and tests and eventually picks the five it wants to build into a pack.

Most of the time, a game starts as somebody’s silly concept, or a unique spin on a traditional party game. Then they’ll sketch it out on paper and distribute it to other team members.

“It’s a big part of the daily culture at Jackbox, which is, ‘I’ve got a dumb idea,’” Laban said. “We paper-test everything initially.”

It’s often as simple as a slip of paper with fill-in-the-blank prompts. (“We have a cutting board that gets a lot of use at the office,” Laban said.) Others quickly prototype crude versions of their game on the Jackbox engine.

Then they play, play, play. Team members are often lured in with pizza to play-test games during lunch. Sometimes it’s three players. Other times it’s eight. (They need to make sure the game is fun for various group sizes.) After playing, they’ll discuss what works and what doesn’t, and walk through the emotions they felt while playing. Then, they’ll iterate on the game, and try it out again the next week. This process can last for months.

Jackbox also relies on external testers. The company has a list of people it brings in to play in-development games, whom they’ll survey. The studio’s designers also keenly watch Twitch streamers. They listen for laughter — and frustrations.

“The directors and designers try not to take prescriptive notes from the players and the testers, because everyone’s got opinions about how things should be done,” Laban said. “It’s mostly trying to solve frustrations or general bigger ideas, [such as] ‘I wish there was a feature that would do this.’ Those types of prescriptive notes are interesting, but they usually point to a bigger problem. Like, why are people asking for that feature? It’s a matter of observing and playing.”

“We’re always coming up with a different take, but still try to hit similar emotions.”

These days, Laban and the rest of Jackbox Games’ designers are rarely surprised by user feedback about their games. They have a pretty good idea of what pacing and rhythm works. They have a firm handle on how much time to allot players to input their answers. Their job is to see how far they can push the boundaries of the form, and what new directions they can take game concepts in without deviating too far from the principles they know work.

“We’re always coming up with a different take, but it’s still trying to hit similar emotions. And most of those emotions have to do with laughing, having a good time, making stupid jokes and making your friends laugh,” Laban said. “There’s nothing more gratifying.”