It’s impossible to know how far away your destination is if you don’t know how far you’ve already come.

This is the true purpose of the product roadmap. It’s not about impressing investors. It’s not about delighting customers. It’s not about motivating employees. Sure, it can be all of those things, but if you’re building your product toward any one of those purposes, you’ll probably fail at all of them.

4 Must-Haves for a Product Roadmap

- Model company goals (initiatives, projects and programs) into actions.

- Build the goals into the roadmap.

- Include concision, flexibility and adherence to company goals.

- Measure progress by finding balance, not showcasing overachievement.

I know. I’ve done it.

In more than 20 years of building high-growth startups, across various industries and at all levels of technical complexity, I’ve learned that one of the more difficult parts of the growth phase is pulling the signal out of the noise, confidence out of chaos and real progress out of perceived progress.

A common tool used across those challenges is a product roadmap, which is a list of features documented out from now to near to far. It’s often a misunderstood document, treated like a homework assignment that has to be tackled before the real work gets done.

I totally get that. I’m a maker and a doer at heart, but I’ve learned the hard way that making and doing without direction is essentially play time. Nothing wrong with play time, of course. But ask any professional athlete and they’ll tell you they don’t get paid to play the game. They get paid for everything else around those couple of hours of play time.

A roadmap will always show you true north. Just like any navigation system, the turn-by-turn directions wouldn’t work without the GPS telling you where you are, and more importantly, how far you’ve come. Once you know that, you can calculate, with pretty decent accuracy, how far there is to go and the arrival time.

You are your startup’s GPS. Let’s talk about how to track your startup’s progress against your roadmap.

A Trackable Roadmap Starts With Goals

This post is the fourth and probably final installment in a loose series on developing a product roadmap at startup speed; it’s about planning for the future while maintaining velocity and flexibility in the present. You don’t have to dive into every post unless you want to go down the product roadmap rabbit hole, but for context, here’s the TL;DR:

- The foundation of any product roadmap should be company goals modeled into actions.

- Once the goals are documented, the initiatives, projects, and programs that make up those goals become your product roadmap.

- To survive a startup’s breakneck velocity, the product roadmap must be concise and flexible, while unwavering in its adherence to the company goals.

When you build a product roadmap with a foundation in company goals, you are getting closer to getting buy-in from all sides of your company and getting closer to ensuring that the progress you’re tracking is real progress.

Now, how do you track real progress?

Did You Do What You Said You Would Do?

Another mistake in the roadmap process is tracking the wrong kind of progress. Just like any road trip, you use your map to break down the path to your ultimate destination into manageable, time-constrained chunks. At the end of the day, when you’re measuring progress, what you’re asking is: “Did we get where we said we were going to go today?”

Not: “Did the car look really cool?”

Not: “Did we stop for a really great lunch?”

Not: “How fast did we get there?”

Those things might be important for the overall journey, but not in the context of the roadmap. When you’re measuring progress against the roadmap, what you’re asking is: “Did we do what we said we would do?”

Not: “Did we profit?”

Not: “Did we win?”

Not: “Did we grow?”

Roadmap progress is much more basic and should inform all those other questions. Here’s how it works. And there’s a twist at the end.

A Simple Metric For a Simple Question

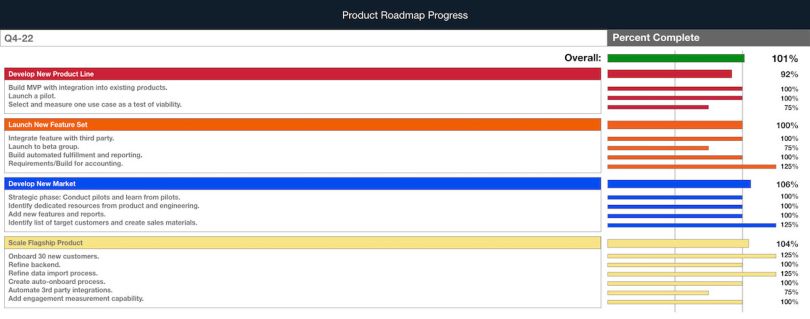

Here’s a dummied-up sample of what I use to track progress. Note that in the real world, there’s a lot more going on and it’s not as generic as I’ve made it here. But the right side, the measurement side, looks almost exactly the same.

For each summary entry on the roadmap (i.e. Develop New Product Line), I’ve broken out all the initiatives, projects and programs we said we were going to tackle that quarter, including how far we said we were going to get (full build vs. design vs. planning).

The measurement is simple and has just a few rules. You can do it your own way, of course, but what I like to do is measure on a scale from zero percent to 125 percent, broken down into 25 percent chunks. For example:

125 = We did more than we said we were going to do.

100 = We did what we said we would do.

75 = We almost did what we said we would do and it’s close enough not to worry about it next quarter.

50 = We got tangled and this is going to bleed into the next quarter.

25 = We got waylaid and this will need rethinking.

I rarely use zero, because sometimes we reprioritize mid-stream. What startup doesn’t? When that happens, the progress becomes NA and I don’t count that initiative when I’m adding the scores because it basically means we changed what we said we were going to do and we need to reserve that right.

Roadmap Progress Is About Balance, Not Achievement

Here’s that twist I promised. The final mistake made in the roadmap process is trying to achieve 125 percent on as many initiatives as possible or to achieve the highest overall score.

This is not how we want to score a roadmap.

Again, just like a road trip, if you’re able to hit 125 percent of what you said you were going to do across the board, you’re doing one of of two things:

- You’re borrowing fuel, resources and energy from tomorrow to pay for today.

- You’re underestimating your capacity. Some would call it sandbagging. Investors and boards don’t like that.

We want to get as close to 100 percent as possible. It would be naive to think that can be done on each and every single initiative. That would mean that priorities and external factors don’t change. With a startup, we know those things change almost daily.

So for each grouping of initiatives, we want to get close to 100 percent. And the overall score should especially target 100 percent on the nose.

What that balance shows is a machine that knows what it can do, achieves what it says it can do, and can use that confidence to outperform in the areas that matter — growth, revenue, innovation and operations. The product is the machine that makes success happen in all those areas. It should be well-oiled, balanced and humming, not overheating.