There’s an often misunderstood metaphor in the startup universe about how building a high-growth startup is like building a car while it’s speeding down the highway.

How do you plan for that without losing hard-won progress? Or more importantly, without losing buy-in from your team, let alone your board and investors?

4 Rules of the Road for Product Roadmap Development

- Set goals, then communicate and document them.

- Be flexible.

- Be direct for execution and vague for growth.

- Don’t try to predict the future, but prepare for it.

I just delivered our company’s product roadmap for the last quarter of this year and all of next year. Complete. Thorough. On one page. I feel pretty good about its chances of survival as everything changes around us, from our ever-shifting internal priorities to the unprecedented magnitude and pace of upheaval in the global economy.

It’s a lot to juggle. But this isn’t the first time I’ve developed a unique roadmap for a high-tech, high-growth startup. I didn’t just create a document out of thin air. It took time to deliver a document that will remain relevant for more than just a couple of weeks.

It all starts with goals.

Goals Don’t Change. They’re Rarely Understood.

This post is the third in a loose series on the unique needs of a startup when it comes to developing a roadmap. The key factor that makes those needs so unique is known as velocity, which, for our purposes, can be defined as the intensity at which a startup has to produce in order to survive.

A high-growth startup is always at breakneck velocity, which I alluded to when I talked about how everything from priorities to economic factors changes, potentially drastically, from one day or one week to the next.

At that kind of velocity, a startup’s roadmap has to be flexible, has to bend and not break, has precious little room for error, and has to be brief and to the point. I can’t tell you how many companies, startups and large corporations alike, develop a product roadmap every quarter and then essentially tuck it into a drawer, never to be seen again.

Big, deep-pocketed corporations can get away with this. When a startup does it, it’s a death sentence.

The drawer thing usually happens because the product roadmap developed at startup speed is often valid for only a very limited period of time. That happens because the roadmap is just a random list of features, prioritized differently by different factions of the company, and unrelated to the company’s overall goals.

When you look back at why a roadmap gets shelved or ignored, it’s not because the goals changed. It’s because the goals were never communicated or even documented in a way that makes sense in the context of what the company is producing: the product.

In the prior post in this series, I reviewed how to get from company goals to product context to a goals-based product roadmap. In this post, I’ll walk you through how to get that roadmap into a one-page document that can survive startup speed.

In a future post, I’ll show you how to track your progress against this roadmap. For now, understand that this roadmap gets you from company goals all the way to tracking progress against those goals, something a roadmap absolutely must do.

Be Direct For Execution and Vague For Growth

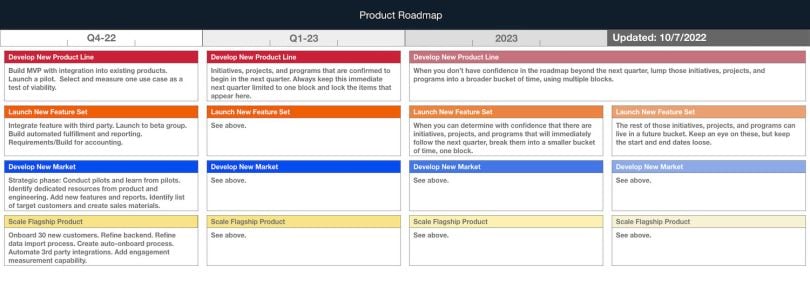

Here’s a sample of the roadmap I put together. Note that the real one has more entries down the page and much more content in each entry.

Let’s talk about why some boxes are smaller than others.

I don’t have to tell any product developer or engineer that the further out you want to predict, the more wrong you’re going to be. But for some reason, this rule gets tossed out the window when developing the product roadmap. Then it always bites us three or six or nine months down the road when everything we said we were going to do didn’t even get started.

So why do we still lump everything into a product roadmap like we would into a project plan?

I actually know the answer to that one. Because it’s the first crutch we have to grab when the product roadmap isn’t goal-based.

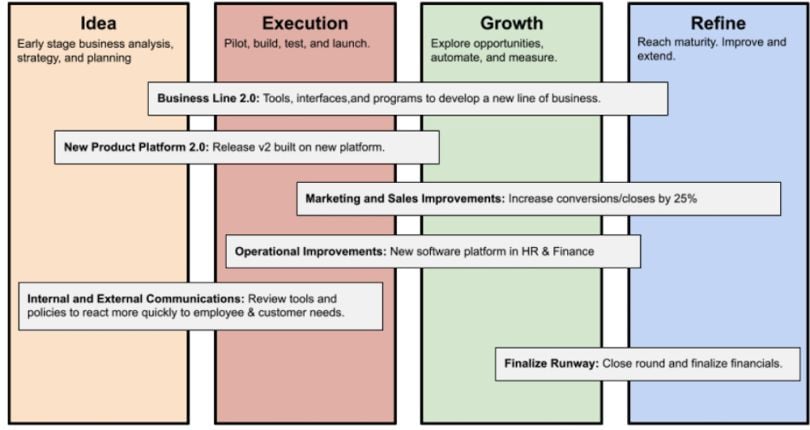

A goal-based roadmap starts with a document that maps each goal from idea to execution to growth to refinement.

Once the goals themselves are broken down into epics, initiatives, projects and programs, only those items that fall into the idea and execution phase of the overall goal should be modeled within a tight time frame. Any item to do with goal growth or refinement should be kept vague and loosely mapped.

Here’s why. First, any goal in the idea or execution phase will result in growth initiatives drastically different than those that can be visualized today. Second, as internal priorities and external factors change, those goals won’t change, but the focus on them will. Locking those items into specific calendar slots now reduces flexibility and, to be honest, forces deviation from the single source of truth.

We’re not fortune tellers. There’s no sense in trying to predict the future, just prepare for it.

A Map Is Meaningless Unless You Know the Destination

Back to our speeding car metaphor: Not only is that car necessarily going to change as we dangerously careen down the road, the road is going to change too. The destination will not, and that destination is defined by the goals.

The roadmap should be locked in for this quarter and, to the best of your ability, next quarter. After that you should be tracking against goal milestones you want to hit — the destination, not how to get there.

When you do that, even the most critical eyes, and that’s usually your investors, will understand the roadmap and buy into it. And when you reach the end of the quarter and track progress and revise, your new roadmap won’t look entirely different, because the destination will still be the same.