Inversion of control may seem like a complex technical topic, but chances are you’re using it in your code already. The main principle of IoC is that, instead of determining when and how to call our code, we let something else do it for us. This could be an HTTP framework like FastAPI in Python or event handlers in JavaScript. For complex applications, we can use dependency injection, which is a form of IoC. Using dependency injection makes our code simpler and more testable.

Here, we’ll explore advanced use cases of IoC and DI, including the “Hollywood principle.” I’ll be using Python to demonstrate the examples, but the same principles apply in other languages.

What Is Inversion of Control?

Inversion of Control (IoC) is a principle where the framework, instead of the developer’s code, determines when and how a piece of code is called. It adheres to the maxim, “Don't call us, we'll call you,” i.e., the “Hollywood principle.”

Inversion of Control Introduction

Let’s start thinking about inversion of control in its simplest form. The definition states that we don’t control when our code is called. Imagine we have a function calling framework that’s given a function that it calls. We don’t control when our function is called. Instead, the framework does, even if it does so immediately.

def greet():

print("Hello")

def framework(func):

# framework decides when to call our function

func()

framework(greet)

framework(lambda: print("Another implementation"))This may seem like a trivial example, but it’s IoC in its purest form. In this case, framework is a simple method that just calls the given function. Framework could decide to do introspection, logging, error handling, sleeping or anything else it needs to do around our func. By calling framework(greet), we don’t know when greet will be called, if ever.

It’s important to note that IoC is an umbrella principle with concrete patterns such as dependency injection. Many frameworks use IoC as a principle to enable reactive applications (i.e., React, Asyncio, FastAPI, Django, etc.).

const onBtnClick = () => console.log("clicked");

const MyApp = () => {

return (

<button onClick={onBtnClick}>Click me</button>

);

};In React we specify an onClick method for a button. We don’t control when onBtnClick will be called; that’s left up to the framework (React).

async def main():

print("Running main...")

asyncio.run(main())Similarly, in Python, using asyncio.run will create an event loop, and our main function call will be added to the event loop. We aren’t controlling when it will run.

app = FastAPI()

@app.get("/users/{user_id}")

def get_user(user_id: int):

user = ... # lookup user by id

return {"user": user}If you’ve ever used a web framework, you’ve likely used IoC without knowing it! In the above example, FastAPI is our framework, and it decides when to call our get_user method. Even though we declare the route, we don’t determine when the method will be called.

This brings us to the “Hollywood principle.” Put simply, this is “Don’t call us, we’ll call you.” This maxim applies to Hollywood stars but also to inversion of control. Imagine a framework that provides a base class called AppBase with a run method. The framework also allows definition of an on_start method. The framework AppBase decides when to call on_start even though we’ve defined the method.

class AppBase:

def run(self):

print("Starting app")

self.on_start() # calls our hook method

print("App finished")

def on_start(self):

# default behavior (can be overridden)

pass

class MyApp(AppBase):

def on_start(self):

print("MyApp is starting!")

app = MyApp()

app.run()

Dependency Injection

A common implementation pattern of IoC is dependency injection. This approach focuses on how services (or classes) are constructed in your application. The same IoC terminology still applies but in a slightly different way.

Imagine a web endpoint that registers a new user. What services does it need to interact with? We need a database to persist the user’s information, an email client to notify the user, S3 for uploading their avatar and a webhook client to notify subscribers. Without DI, our code would look like this:

@app.post("/users")

def create_user(request_data: dict):

db = DbClient(dsn="postgres://...")

email_service = EmailService(smtp_server="smtp.example.com")

storage = S3Storage(bucket="user-avatars")

webhook_service = WebhookService(api_key="secret-key")

# Business logic

user = {

"name": request_data["name"],

"email": request_data["email"],

}

db.insert_user(user)

storage.upload_avatar(user_id=user["id"], file=request["avatar_file"])

webhook_service.notify_user_created(user)

email_service.send(

to=user["email"],

subject="Welcome!",

body="Thanks for signing up."

)

return {"status": "ok"}Every other endpoint that wants to use these same services needs to construct them the same way, and we end up with copypasta everywhere. Even if we move their creation to separate functions like get_db or get_email_service, is it any better? It might be in the short term, but long term, it will be a pain to test and continue to manage.

def setup_test_client():

test_client = TestClient(app)

mock.patch("myapp.db.get_db")

mock.patch("myapp.email.get_email_service")

mock.patch("myapp.s3.get_s3")

...

return test_clientOur test code requires mocking the methods at every call site. When we forget, our tests will break or call a real service. But let’s invert the control of how our services are constructed and see how this is better for tests and endpoint code readability.

@app.post("/users")

def create_user(

user_in: UserCreate,

db: DbClient = Depends(get_db),

email_service: EmailService = Depends(get_email_service),

storage: S3Storage = Depends(get_storage),

webhook_service: WebhookService = Depends(get_webhook_service),

):

# Business logic only

user = db.insert_user(user_in.dict())

storage.store_avatar(user_id=user["id"], avatar_url=user_in.avatar_url)

webhook_service.notify_user_created(user)

email_service.send_welcome_email(to=user["email"])

return {"status": "ok", "user": user}By writing our endpoint code this way, the endpoint itself is only business logic. The endpoint doesn’t care about how the services are created; it just wants to consume them. FastAPI uses the Depends marker to tell the framework how to construct our services. By default, the service will be created on each HTTP request, but we’ll discuss alternatives later on. Let’s see how we could override our dependencies for tests.

def setup_test_client():

fake_db = FakeDbClient()

fake_email = FakeEmailService()

fake_storage = FakeStorage()

fake_webhooks = FakeWebhookService()

app.dependency_overrides[get_db] = lambda: fake_db

app.dependency_overrides[get_email_service] = lambda: fake_email

app.dependency_overrides[get_storage] = lambda: fake_storage

app.dependency_overrides[get_webhook_service] = lambda: fake_webhooks

return TestClient(app)We do this once when setting up our TestClient, and all routes using the dependencies will be properly overridden. There’s no mocking needed!

Types of Dependency Injection

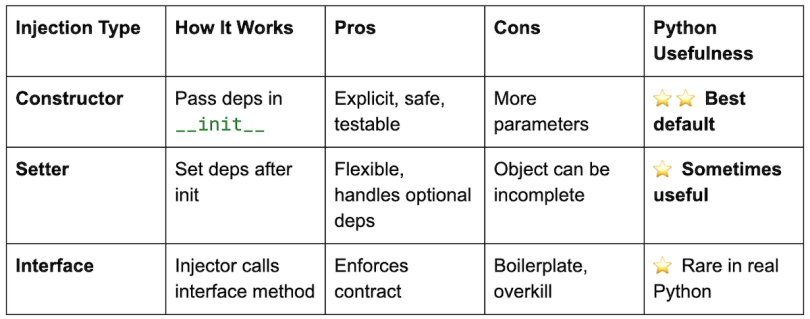

Dependency injection becomes more powerful when we have many services and some rely on one another. DI allows a single way to define and request dependencies. Thus far, we’ve focused on constructor injection by creating our services and passing required dependents into the construction of the class. We’ll briefly touch on two other ways we can use DI, although they’re less common.

The first alternative is called setter injection, which allows injecting dependencies with a setter method like set_email_service. This can be useful if some dependencies are optional, circular or require lazy setup.

class UserService:

def __init__(self):

self.email_service = None

def set_email_service(self, svc: EmailService):

self.email_service = svcIn this case, maybe EmailService isn’t a hard dependency of UserService, and it can function without it. This approach introduces more complexity to our services since we must check if email_service is set before using it.

Another alternative is called interface injection, which was historically a common way to inject dependencies. This approach is rare in Python, but we can still visualize it when thinking about a plugin system.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class Plugin(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def inject_logger(self, logger):

pass

def load_plugin(plugin: Plugin, logger):

plugin.inject_logger(logger)With this approach, plugins are defined based on a common interface, then dependencies can be injected based on the interface. This is similar to the setter approach since we define a method to set the dependency but is unique since the methods are defined with an interface (or ABC in Python).

Let’s wrap up this section by covering the differences between DI pushing dependencies versus service locator, which pulls dependencies. The service locator pattern requires having a central registry for dependencies and also requires looking them up. This pattern can hide which dependencies a class uses, which makes testing more difficult as well as looking quickly at a service to see what dependencies it uses.

# With Service locator

class UserService:

def register_user(self, email):

# Hidden dependency

email_service = ServiceLocator.get("email_service")

email_service.send(email, "Welcome")Testing this service requires calling ServiceLocator.override("email_service", FakeEmailService()) which ends up looking strikingly similar to our original mocking approach. We prefer constructor DI for its clarity.

class UserService:

def __init__(self, email_service):

self.email_service = email_service

def register_user(self, email):

self.email_service.send(email, "Welcome")

Advanced Dependency Injection

Eventually, after using DI for some time, you’ll start to realize your services need to be set up when the app starts. Also, some services you only want to create once, while you should create others per request. We’ll focus on two ways to accomplish these advanced forms of DI. The first will use FastAPI’s builtin DI, and the second will use the dependency_injector package.

Lifecycle

When using dependency injection, it’s important to think about how we’re interacting with our services since we’re no longer in control of when they’re used. When using a database it’s important to think about when to connect to it, especially for connection pooling. Similarly, we may want to keep an HTTP session around for re-use.

FastAPI provides a lifespan parameter where we can set up and tear down services that require it. Anything before the yield is setup code, and anything after is teardown code.

from fastapi import FastAPI

from contextlib import asynccontextmanager

@asynccontextmanager

async def lifespan(app: FastAPI):

await db.connect()

await s3.init()

yield

await s3.close()

await db.disconnect()

app = FastAPI(lifespan=lifespan)The problem with this approach is that, as our number of services grow, so does our lifespan method. This is where the dependency_injector package shines.

class Container(containers.DeclarativeContainer):

config = providers.Configuration()

db = providers.Resource(

DB,

dsn=config.db.dsn,

init=DB.init,

shutdown=DB.shutdown,

)

s3 = providers.Resource(

S3Client,

endpoint=config.s3.endpoint,

bucket=config.s3.bucket,

init=S3Client.initialize,

shutdown=S3Client.close,

)

@asynccontextmanager

async def lifespan(app: FastAPI):

await app.container.init_resources()

yield

await app.container.shutdown_resources()As we add more services, we don’t have to worry about updating the lifespan function. The Container will handle it for us.

Scope

How can we scope the user service to be created per request rather than just once? In FastAPI, this is the default behavior when using Depends, but dependency_injector requires providers.Factory.

class Container(containers.DeclarativeContainer):

# <snip>

# short-lived factory for request-scoped business logic

user_service = providers.Factory(

UserService,

db=db,

s3=s3,

)For single set up and tear down, we can use providers.Resource like the previous example and if we don’t need setup and teardown, we can use providers.Singleton.

If everything so far feels a little vague or magical, don’t worry. In the next section, we’ll dive into how this all gets wired up.

Wiring

Let’s imagine again that we’re building our own Container that has the ability to auto-resolve and build services for us. We can use the inspect library to look at parameter names, and if one matches a registered provider, we can build it.

import inspect

class Container:

def __init__(self):

self._providers = {}

self._singletons = {}

def register(self, name, provider):

self._providers[name] = provider

def resolve(self, name):

# return existing singleton if present

if name in self._singletons:

return self._singletons[name]

provider = self._providers[name]

# If provider is a class, autowire its constructor

if inspect.isclass(provider):

instance = self._build_instance(provider)

self._singletons[name] = instance

return instance

# If provider is a factory function

instance = provider()

self._singletons[name] = instance

return instance

def _build_instance(self, cls):

sig = inspect.signature(cls.__init__)

params = list(sig.parameters.values())[1:] # skip 'self'

# automatically resolve constructor arguments

kwargs = {

p.name: self.resolve(p.name)

for p in params

}

return cls(**kwargs)

class UserService:

def __init__(self, db_client: DbClient, email_service: EmailService):

self.db = db_client

self.email = email_service

def create_user(self, email):

self.db.query("INSERT INTO users ...")

self.email.send(email, "Welcome!")

return {"status": "ok"}And then use it:

container = Container()

container.register("db_client", DbClient)

container.register("email_service", EmailService)

container.register("user_service", UserService)

# autowiring kicks in here

user_service = container.resolve("user_service")

response = user_service.create_user("[email protected]")

print(response)When calling container.resolve(``"``user_service``"``), our DI container will look up db_client and email_service based on their names. This is the convention over configuration approach. We use conventional names to reference our services. If we used email_svc as the parameter name, we’d get a key error looking up the provider.

The alternative, which is more robust, is the configuration approach, where we specify where the dependencies come from but still use autowiring to inject the dependencies into our code.

# container.py

class Container:

...

user_service = providers.Factory(

UserService,

db=db,

s3=s3,

)

# app.py

from fastapi import FastAPI, Depends

from dependency_injector.wiring import inject, Provide

app = FastAPI()

container = Container()

container.wire(modules=[__name__])

@app.post("/users")

@inject

def create_user(

payload: dict,

user_service: UserService = Depends(Provide[Container.user_service]),

):

...By using the configuration approach, we are explicit about how our dependencies are created within the Container but still rely on dependency injection to inject the concrete dependencies into our methods.

The zen of Python instructs us that “explicit is better than implicit.” I think that applies well to IOC and DI. The “magic” still happens at injection time, but it’s still up to you to ensure the proper dependencies get hooked together.

Extensibility and Aspect-Oriented Programming

As our applications get bigger and more complex, we need more structured ways of handling common patterns, whether error tracking, logging, caching or even security. One way to manage this is through aspect-oriented programming (AOP). Instead of each method being responsible for calling the appropriate method to log, make a db session or verify a user’s identity, the IoC container can manage this for us.

Let’s imagine two use cases: logging method call times and having one database transaction for a method that autocommits or rolls back.

def log_calls(fn):

@functools.wraps(fn)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

start = time.time()

print(f"[LOG] Calling {fn.__name__} with {args[1:]}, {kwargs}")

result = fn(*args, **kwargs)

duration = (time.time() - start) * 1000

print(f"[LOG] {fn.__name__} returned {result!r} in {duration:.2f}ms")

return result

return wrapper

def transactional(fn):

@functools.wraps(fn)

def wrapper(self, *args, **kwargs):

self.db.begin()

try:

result = fn(self, *args, **kwargs)

self.db.commit()

return result

except Exception:

self.db.rollback()

raise

return wrapperBy writing decorators, the methods using them don’t need to be aware of how they work to achieve their goal. If we have an order service, we can wrap the place_order method with @transactional, which will ensure all database updates happen in a single transaction, still using the order service’s db.

class OrderService:

def __init__(self, db):

self.db = db

@transactional

def place_order(self, user_id: int, items: list[int]):

# no explicit transaction code here

self.db.insert_order(user_id, items)

self.db.decrease_inventory(items)

return "ok"Both transactional and log_calls can be used to wrap methods rather than directly decorate too. This is helpful when the decorators are optional, like logging.

class Container:

def __init__(self):

self._singletons = {}

def payment_service(self) -> PaymentService:

if "payment_service" not in self._singletons:

service = PaymentService()

if logging_enabled:

service.charge = log_calls(service.charge)

self._singletons["payment_service"] = service

return self._singletons["payment_service"]

Tests

Writing fast integration tests is one of the highest value adds to any codebase. IoC and DI enable you to do this easier and more reliably than any other approach. This is not to say that you shouldn’t use mocking; you still can, and DI makes it better. Let’s look at testing a user service which uses the email service and database.

Before DI, we’d need to use mocking to patch everywhere the EmailService is instantiated. And maybe we forget to mock the db altogether.

def test_user_service_sends_email():

mocked_email_svc = mock.patch("demo.user_service.EmailService")

user_svc = UserService()

user_svg.handle_user_creation(...)

mocked_email_svg.send_email.assert_called_with(...)Using DI, we pass a test-only MockEmailSvc and a MockDb. We can access the sent_emails attribute that’s only available here and verify the expected result. The MockDb could be in-memory, sqlite, or even local postgres. By using IoC and DI, it doesn’t matter. That’s the power!

def test_user_service_sends_email():

db = MockDb()

email_svc = MockEmailSvc()

user_svc = UserService(db, email_svc)

user_svc.handle_user_creation(...)

assert email_svg.sent_emails.len() == 1

Get Familiar With Inversion of Control

Inversion of control helps reduce tight coupling by having containers call your code rather than your code calling other code directly. This is the Hollywood Principle: “Don’t call us, we’ll call you.” By having your code reference other classes through dependency injection, you rely on the methods available as an interface rather than relying on how the other class is constructed. This reduces the coupling of classes and services.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the tight coupling problem that inversion of control is fundamentally designed to solve?

IoC solves the tight coupling problem that happens when application code controls everything: object creation, configuration, flow, and dependencies. This tight coupling makes code brittle, hard to test, hard to swap implementations and hard to grow. IoC inverts that relationship by having frameworks control flow, containers construct dependencies so your code just receives what it needs.

How does constructor injection ensure the integrity of an object's dependencies compared to setter injection?

Constructor injection ensures dependency integrity because all required dependencies must be provided when the object is created. This ensures the object can never exist in a partially initialized or invalid state. Setter injection is more flexible but will cause a runtime error if a dependency hasn’t been set.

In the context of IoC, what is the specific function of the service locator pattern, and why is it often considered an anti-patt

The service locator pattern provides dependencies on demand through global lookup, but it’s considered an anti-pattern because it hides dependencies, makes testing more difficult and can tightly couple your code to the locator rather than keeping dependencies explicit.

How does an IoC container manage the difference between a singleton and a transient dependency scope?

IoC containers use a private cache (dict or HashMap) for singleton dependencies. For transient dependencies, nothing is cached and the dependency is created each time it’s requested. The dependency_injector library has these as builtin providers. FastAPI requires the use of lru_cache or singletons; all other dependencies are transient.

What mechanism does an IoC container use to integrate aspect-oriented programming (AOP) concerns like logging or transaction man

Generally the IoC container can wrap methods or whole classes using AOP. Concretely in Python, this can be a decorator (as previously shown) or a proxy object.

class LoggingProxy:

def __init__(self, target):

self.target = target

def __getattr__(self, name):

attr = getattr(self.target, name)

if callable(attr):

def wrapped(*args, **kwargs):

print(f"[LOG] Calling {name}")

return attr(*args, **kwargs)

return wrapped

return attr

# elsewhere

user_svc = LoggingProxy(UserService())

Explain the concept of Poor Man's DI and when it might be an appropriate solution over a full IoC container.

- A Poor Man’s DI might look like our

Containerwithinspectexample from above. It’s a simple python object that uses argument naming convention for injecting dependencies. There are a few situations where usingdependency_injectoror another existing solution like FastAPI’s DI. - If you need more control over the objects and how they’re created, especially if you want to use AOP with proxy objects rather than decorators.

- The other situation is if it genuinely doesn’t fit in with the framework you’re using. Django specifically makes it a bit difficult to separate the db-layer from business logic.