Among dozens of cities that aspired to be one of the top tech hubs, how did Seattle become one of the two leading centers of technological invention in the world? Why did Jeff Bezos decide to base his internet bookstore here, rather than in Silicon Valley or staying in New York City? Why did home-grown entrepreneurs like Craig McCaw and Bill Gates set their roots down here? Even before them, the companies that gave us the first commercially successful ultrasound imagers, heart defibrillators and barcode readers sprang up in Seattle.

Why not Minneapolis, Memphis, or Minsk? Why does Seattle continue to be a place that nurtures the development of breakthrough technologies?

All roads lead back to our economic flywheel.

Strictly speaking, a flywheel is a mechanical device, a wheel to which force is applied, creating a rotation that releases energy. Without additional force to turn it, friction will gradually slow the wheel to a halt. But if sufficient new force is applied, the wheel spins faster and faster, creating still more energy that keeps it spinning.

Flywheels have been around for at least ten thousand years — potter’s wheels are flywheels. James Watt used a flywheel in his eighteenth-century steam engine that powered the Industrial Revolution.

I was first introduced to the notion of a flywheel as an engine for growing a business at a meeting of Amazon’s board of directors in the fall of 2001. We were in the midst of the dot-com bust, and the company was losing lots of money. Jeff Bezos had assembled his S-team of ten senior executives and board of directors to hear from the management consultant Jim Collins, author of the bestselling book Good to Great (2001).

Collins talked about the concept of a business-centric flywheel, which he explained as the effect of numerous small initiatives acting upon each other. Like compound interest, he said, the growth would be slow at first but gain momentum over time.

Flywheel: An Example

The economy was highly stressed. The NASDAQ had peaked in March 2000, and now, with the dot-com bubble burst, a recession had set in. Financial markets that had been wildly positive about internet companies during the late 1990s, showering the sector with venture and public capital, had grown jittery — especially bondholders, and Amazon had raised several billion dollars through bond issues. The company’s stock fell from over $100 a share to $6.

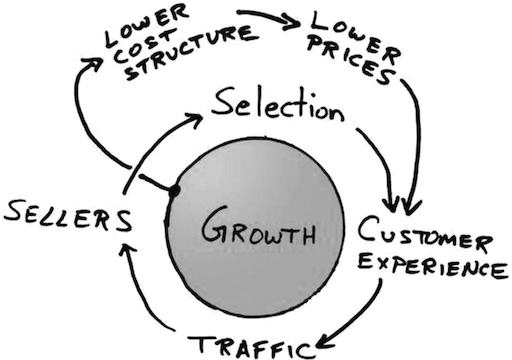

But Bezos was focused on the long term. He’d invited Collins to talk to the board and senior managers about sustainable growth, so Collins drew for us an Amazon-specific flywheel. It showed a virtuous cycle, where low prices brought in customers, and more customers allowed Amazon to add more products for sale, the volume reducing prices further and attracting still more customers in a gradually accelerating flywheel.

Bezos liked this concept, and the flywheel — with a few Bezos modifications — became a key part of his guiding philosophy at Amazon. The Amazon flywheel is centered on growth. To generate momentum, it begins by providing buyers a marketplace with great product selection, convenience and low prices. As consumers are attracted, traffic increases and Amazon can offer more products at lower prices, improving the customer experience, which attracts still more customers. As Amazon grows, the flywheel spins faster and faster.

Amazon also uses innovative business processes — such as opening the site to third-party sellers. They appreciate the ease of selling and shipping products through Amazon. The company benefits from a vastly increased inventory, and competition among the sellers lowers prices. The flywheel concept quickly became integrated as a guiding principle at Amazon, which then conceived new flywheels for its Prime and video divisions.

To explain the increasing momentum in Seattle, I thought back to that afternoon with Jeff and the Amazon team. Board members in the room, in addition to Jeff and myself, were venture capitalist John Doerr, then Gates Foundation CEO Patti Stonesifer and Intuit founder Scott Cook.

In 1995, after becoming one of the first investors in Amazon, I had no idea that the tiny startup would become one of the most valuable companies in history.

At my firm, Madrona Venture, we talk about the three pillars of Seattle’s innovation economy: invention, entrepreneurs and funding. As I pondered, it became obvious that the most accurate and dynamic way to think about Seattle’s economy is with the concept of a flywheel. In Seattle’s version, it begins with talented people — entrepreneurs, inventors, and leaders — who create innovations which begets startups. Startups spawn successful companies that then attract talented people who create innovations. Successful companies also generate wealth and jobs, which provides the energy to support the new startups that those creative people inevitably launch. And so the cycle continues.

As more talented people move to Seattle, more innovations give rise to new companies, which attract more creative people, and the flywheel accelerates.

This is a useful way to look at the growth of Seattle’s high-tech economy and a model for other cities to emulate when growing their own economies. But how did this flywheel get going before we had lots of creative people, inventions, capital, startups and successful companies? How did Seattle become a world leader in aviation, software, wireless communication, biotechnology, the cloud and online retail? How did we become a leading place for innovation of all kinds?

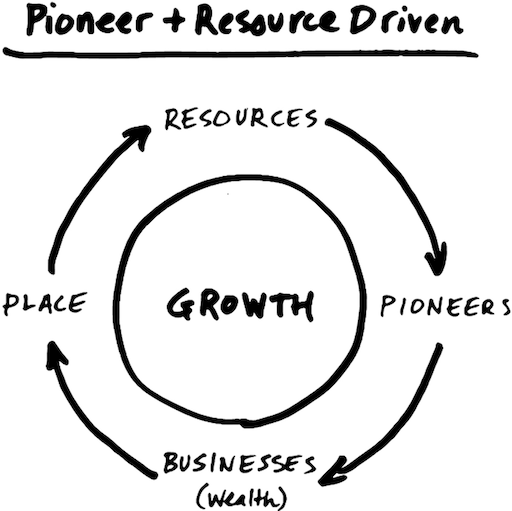

The way I see it, Seattle has had two economic flywheels — one that generated its early growth and one that generates momentum today. What the two have in common is a beautiful setting with plenty of opportunities that attract pioneering, entrepreneurial types, and keep them here.

A resource-based flywheel is, however, a dead end. The exploitation of resources does not beget more resources — generally, it depletes them. Timber, fish and gold could never power the long-term growth of a Pacific Northwest economy. Trade, likewise, was alone not enough to sustain Seattle. Though city officials liked to say Seattle had a natural advantage over California in trading with Japan and China because it was ever-so-slightly closer, that one-day ocean shipping advantage was never great enough to outweigh the Golden State’s larger population.

So how did Seattle escape its resource-economy dead-end and move toward a creative-people-and-innovation flywheel? It could have grown incrementally and someday perhaps given birth to a Bill Gates. But its early breakout occurred because of a young man who came to Washington State in 1909 in search of uncut trees.

Seattle’s Flywheel Starts Spinning

The twenty-eight-year-old head of a logging company based in Michigan, William Boeing, purchased timberland in Grays Harbor County, southwest of Seattle, and made good profits shipping lumber east. That same year, on a visit to the Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition in Seattle, Bill Boeing saw an airplane for the first time. He took a flight in a small, single-engine plane and was captivated. More important, he foresaw that aircraft could become the basis for an enormous industry — even many industries. In 1916, Bill Boeing founded an aircraft manufacturing company, and its first offering, a seaplane, was built partially of Washington spruce timber, which was strong for its weight.

The Boeing Company stamped Seattle as an early tech city.

It is highly unlikely that Seattle would have become a world aerospace capital without Bill Boeing. And the Boeing Company stamped Seattle as an early tech city. As it grew, Boeing naturally attracted smart, ambitious people to Seattle, engineers in particular. It also found a ready supply of homegrown talent through local schools like the University of Washington.

By the late 1960s, Bill Boeing’s entrepreneurial venture had become a global leader in aerospace, commercial aviation, military missile production, and Saturn booster rockets for space travel. Seattle appeared in 1970 ideally positioned to give the Bay Area — home to Lockheed, Hewlett Packard, and Intel— some real competition as a talent and innovation magnet.

But then Boeing went seventeen months without selling a single plane to any U.S. airline, laid off seventy thousand workers, and plunged Seattle into its longest, deepest economic trough since the Great Depression.

People fled in droves. “Will the last person leaving Seattle turn out the lights?” bitterly quipped a billboard near the airport. With the Boeing bust and the era’s trend of flight to the suburbs, Seattle suffered a net loss of sixty thousand residents between 1960 and 1980.

Seattle was laying the groundwork for their tech flywheel to begin spinning.

One of my goals, when I returned to Seattle and began at the Perkins Coie law firm in 1967, was to work with Boeing. Bill Allen, Boeing’s CEO since 1945, who’d made a “bet-the-company” decision in 1957 to launch the 707, had been a Perkins partner. By the 1980s, I became Perkins’ lead lawyer on the Boeing account and Boeing’s principal outside attorney.

A Series of False Starts

When the Boeing bust occurred in 1971, the company began an effort to diversify its way back to revenue and profitability. The executive in charge asked me to help them acquire computer service bureaus in major cities that provided batch processing of data for local businesses, such as accounting firms — a very early precursor to today’s cloud services, except that the data was delivered by hand on computer disks. Boeing spent a few million dollars on small acquisitions, but they dropped the idea when it became clear that the business would not scale.

I became involved in Boeing’s most bizarre attempt at diversification in 1972 when I was asked to help them evaluate a proposal to use their computer savvy on behalf of New York City’s off-track betting business. To my relief, the proposal was ultimately rejected. Boeing also created internal word processing and spreadsheet programs that presaged today’s ubiquitous productivity software, and they considered competing with Intel in the design and manufacture of silicon chips. Carver Mead, a professor at Caltech, spent a summer in Seattle teaching silicon design to a group of Boeing employees. When Boeing abandoned its chip project, several of the employees departed to start a new company, Seattle Silicon, that I represented.

Boeing’s heart wasn’t really in any of these businesses. What it wanted was for the airplane industry to recover, which it eventually did. But they missed out on what others built into big businesses. It wasn’t until decades later that traditional airline and auto industries came to understand that they are as much software as manufacturing companies.

The Bright Side of the Boeing Bust

Just as Microsoft mostly failed to participate in the early dynamic growth of the internet in the late 1990s, Boeing missed the early chip and software revolution. Hidden by its commercial and government successes, Boeing had been a traditional manufacturing company all along, with a rigid bureaucracy that stifled invention, entrepreneurship and efforts to launch new ventures. There had been opportunities to become a leader in semiconductors, business software and computer services, but Boeing never doubled down on them.

The Boeing bust helped stimulate a small group of Seattleites to begin building the underpinnings for the tech economy of the future.

Nonetheless, Bill Boeing’s original 1900s entrepreneurialism set the stage for Seattle’s innovation flywheel to come, and ironically the Boeing bust helped stimulate a small group of Seattleites to begin building the underpinnings for the tech economy of the future. Although an elitist Lesser Seattle movement argued against committing to a growth strategy, business and community leaders recognized that Seattle needed to diversify beyond Boeing and aerospace to grow the economy. Without fully planning for it, they began building a diversified tech economy that did not depend on a single company.

Beginning in the 1970s, a few entrepreneurs launched several biomedical and software companies. In addition, a few small local venture firms and investment banks were launched to finance startups and their growth. Local lawyers worked to build the financial and tech expertise to keep the tech legal work from being captured by law firms in New York City and San Francisco.

Seattle was laying the groundwork for their tech flywheel to begin spinning.

As chief outside legal counsel to the Boeing Company in the 1980s, I had watched a global company struggling to maintain its edge in technology. In the early 1990s, as executive vice president at McCaw Cellular Communications, I got an early ground-floor view of the future of mobile communications and the power of innovation.

In 1995, after becoming one of the first investors in Amazon, I had no idea that the tiny startup would become one of the most valuable companies in history, displacing corporate icons like IBM, General Electric and General Motors. But I did grasp that the future of successful cities would depend on attracting talent and creating growing technology firms.

* * *

Excerpted from Flywheels: How Cities Are Creating Their Own Futures by Tom Alberg published by Columbia Business School Publishing. Copyright (c) 2021 Tom Alberg. Used by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.