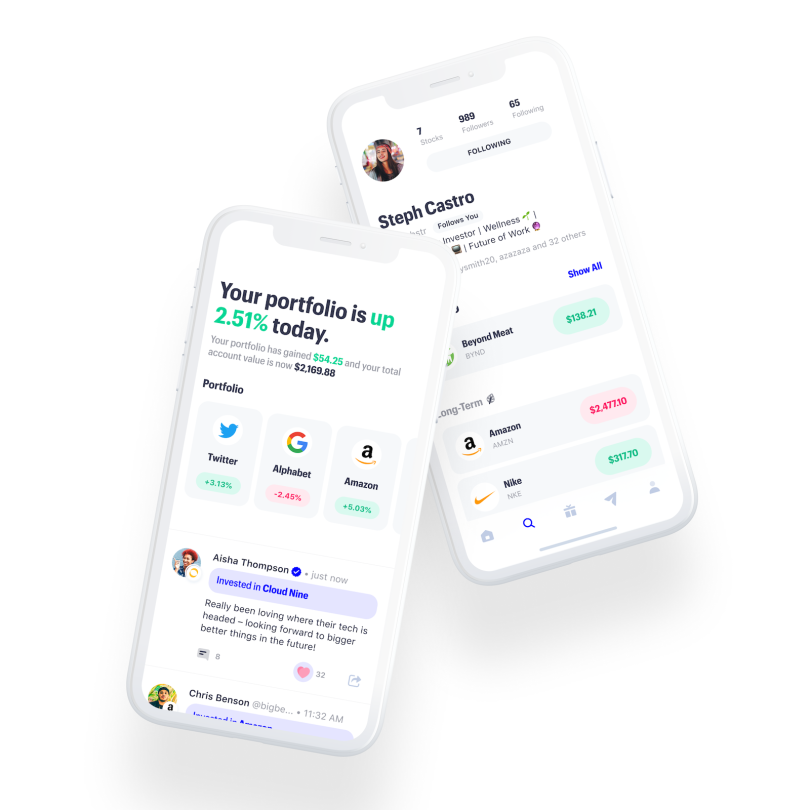

In January of 2021, following investment app RobinHood’s pause of certain stock trades, many retail investors flocked to a similar service called Public, where, upon signing up, they may have been surprised to discover that the app’s main page isn’t a ticker of the latest stock prices — it’s a social feed.

Public’s homepage is an infinite scroll of user-generated posts, where discussions regularly unfold in comments sections underneath. But unlike other social networking platforms, members on Public chat about Tesla’s stock price, explain to each other how special-purpose acquisition companies work and share motivational posts about the importance of patience in long-term investing, complete with plenty of flexed biceps emoji.

It seems as if people are on Public to make conversation as much as they are to make investments.

And maybe they are: The majority of Public users identify as long-term investors, whose trading activities might be few and far between. Connecting with others who share similar interests could be the driving reason they engage with the app in the meantime.

The result is a product so tightly intertwined with community that the former is hardly recognizable without the latter.

While a community-first orientation is an unexpected dynamic for an investment app, the focus isn’t unique to Public. It animates a growing movement of tech startups that put community at the front and center of their business strategies.

The recent declaration “Community-Led Companies Are the Future” is one outgrowth of the community boom. The document was signed by leaders of several tech startups who pledge to build companies where “community is central” to their businesses, not an afterthought tacked onto the list of responsibilities of marketing or support departments.

Some think community’s rising esteem will spell a shake-up in the tech leadership landscape. In five years, predicts Reddit co-founder Alexis Ohanian, “more than half of the top-500 publicly traded companies are going to have a chief community officer.” Community will be such a heavy point of emphasis for companies, Ohanian believes, that it will need representation in the C-suite.

By that time, companies trying to stand out from the crowd — or simply keep up with it — may have to rely on community as the focal point of their go-to-market strategies.

Community Enters the Spotlight

Prioritizing community hardly seems like a new phenomenon for companies. After all, Apple energizes its cult-like following through product unveiling events and keeps a well-tended support forum. GitHub fosters a community ethos among developers and programmers by letting them easily collaborate on code in public. Salesforce draws hundreds of thousands of attendees to its annual Dreamforce conference like it’s Woodstock. And countless others would say they value community too. The concept isn’t new.

What’s changed, though, is the intentionality with which companies are making their communities the main attraction of their brands.

“Community used to be the bastard child of support,” Mac Reddin, co-founder and CEO of Commsor, and organizer of the community-led pledge, told Built In.

Lately, he’s noticed more and more companies creating and investing in community spaces where users are encouraged to interact with each other, not just transact with the brand.

“It’s a difference of valuing community as a core piece of your business versus just bolting a forum on your product.”

Companies like Figma, a web-based tool for designers that allows members to create profiles, follow one another, publish their designs and remix someone else’s. Or Roam Research, a note-taking product that has a vibrant Slack community and connects users with the hashtag #RoamCult. Or Morning Brew, the business newsletter whose audience interactions inspires some readers to include a coffee-cup emoji in their Twitter handles to signal they’re part of the club.

These companies, plus several others — ranging from Atlassian to Peloton, Product Hunt to Notion — create environments where people see themselves as members, not customers.

“It’s a difference of valuing community as a core piece of your business, versus just bolting a forum on your product and calling it a community,” Reddin said.

The Community-Led Growth Flywheel

It’s not hard to see the logic behind this: Customers who feel part of a community are more likely to refer their friends and less tempted to leave for a competitor. They often become brand evangelists too, which is free, effective marketing for the company. And in the case of early stage startups, community members often act as focus groups, giving valuable feedback that companies can use to improve their products more quickly.

The result, theoretically, is growth.

Hence the tidy label recently bestowed on this strategy — “community-led growth.”

The phrase is a play on “product-led growth,” a go-to-market strategy in which companies make their self-serve products the main vehicle for acquiring, activating and retaining users.

Community-led growth “acts as a multiplier on top of product-led growth,” wrote Corinne Marie Riley, an investor at venture capital firm Greylock. It creates a “flywheel of active members strengthening the community.”

You might also think of community-led growth as a remix of the concept Chris Dixon popularized several years ago — “come for the tool, stay for the network” — which is the idea that software companies can acquire users by providing a useful product and retain them by providing community. (Think early Instagram: Come for the retro filters, stay for the social interactions.)

What companies have discovered since then is that community is too powerful a force to be introduced later in the customer journey. When it’s put front and center, community can be an acquisition channel, product feedback mechanism and brand differentiator, not just a retention tactic.

In other words, come for the community and tool, stay for the community and tool.

Community Versus Audience

What counts as having a community? Lots of social media followers? Newsletter subscribers? Web traffic? Maybe even a support forum where users submit product queries?

“It’s a never-ending debate, the audience versus community one,” Reddin said.

For him, community is when member-to-member interactions, rather than business-to-customer broadcasts, are being facilitated and creating value.

“It’s about breaking down barriers so that your customers can actually interact with each other,” he said, “and enabling customers to more directly build those relationships themselves, rather than revolving around you.”

Indeed, making community “all about them” is a common mistake that companies fall prey to, according to Emily Lonetto, head of growth at Voiceflow.

The community space should match the needs of its members, she said, and not be “another avenue where [the company] can just shove product updates to you.”

Community might take place on a social networking platform, or in a Slack group, or on a forum the company created in house. The specific technology stack enabling the connections matters very little. What makes a community work is the mindset, the intentionality. What people care about is the vibe.

Riley, the Greylock investor, told Built In there are two primary types of company-created communities — a community of product, and a community of practice.

A community of product is built specifically around the product the company is selling. Members of this kind of community often share product tips and tricks with each other, and report bugs or submit queries to the company’s support team.

A community of practice, on the other hand, revolves around a generalized concept, rather than a product or service specific to any one company. It unites people who share the same specialization or interest.

Types of User Communities

- Community of Product revolves around a specific product or brand.

- Community of Practice unites members with a shared specialization or interest.

Whether it revolves around a product or a practice, “community has to exist for the sake of community,” Reddin said.

It’s a bit of a catch-22. While a thriving community will naturally benefit marketing, sales and support functions, it can’t be too firmly steered by them.

“Community is about building the cycle of trust and engagement and relationships with people,” Reddin added. “If you are too heavy handed in co-opting that for obvious benefit, people will see through that.”

Why Now Is Community’s Time

Community has always existed in some form or another — Rotary clubs, religious congregations, Neopets forums. Humans are hard-wired to find their people and form groups.

While trust in traditional institutions has waned, the desire to connect with others over shared interests or common pursuits lingers in the human psyche. A year spent in quarantine has probably only exacerbated our collective hunger for connection.

“I think people care more about finding a sense of belonging,” Reddin said, reflecting on why community-led companies have been gaining traction recently.

“You’re not just buying a product, you’re buying into a whole community of people who are passionate about the product and talk about how to use it and share tips and tricks,” he added. “It really elevates the product into something more than a product.”

“You’re not just buying a product, you’re buying into a whole community of people.”

Community also gives brands a way to stand out in a fragmented market, where product features appear to differ very little, and marketing through traditional channels gets expensive.

Willa Tellekson-Flash, community operations lead at Public, told Built In that consumers today are faced with an unprecedented volume of options, and that the brands offering a vibrant community and the promise of connection are the ones that tend to separate themselves from the pack.

“Open the app store, there are tons of finance apps,” she said. “Community, and a sense of being seen and appreciated by a brand, is what drives loyalty and what brings you back.”

And with the popularity of tools like Facebook Groups and Slack, it’s never been easier for companies to create communities and invite people into them.

Are Communities the Future of Tech?

Even though the movement of community-led companies adds to its number every day, a lack of resources may be holding it back from faster growth.

“I think the biggest mistake that a lot of people make,” Lonetto said, “is they want to do a community-led approach, and they don’t have the buy-in for it, they don’t have the resources for it, or they don’t dedicate enough time to really foster it.”

The lack of buy-in and patience from leadership can often be traced back to the difficult time community leaders have had in measuring community success and translating it into terms of how it impacts the business.

“The age-old question with community is always, ‘What does this mean for ROI?’” Lonetto said. “In a lot of cases, communities die off before they even start by trying to answer that.”

Reddin calls it a self-fulfilling prophecy: “Because there’s a lack of understanding of community right now, that leads to a lack of being able to measure community properly, which leads to a lack of proving impact, which leads to this lack of investment, which continues that cycle,” he said.

In time, he believes community leaders will find ways to prove community’s importance to leadership with data.

For now, he suggests tech companies think of community building like an apple tree: Plant the seeds, water it, nurture it, protect it and know that it’s going to be a while before you see any apples.

“But once it bears fruit,” he said, “it’ll bear fruit for a hundred years.”