A sabbatical is a paid period of leave someone takes off work while still remaining employed by their company. It’s a benefit that some companies give to long-tenured employees as a way to reward them for their work.

Sabbatical Definition

A sabbatical is a paid period of time off from work, which some companies offer to employees after a certain amount of years of service. Sabbaticals usually last anywhere from one month to one year, and they provide time and space for workers to rest, travel and learn new skills.

Several companies, including banks Citi and Goldman Sachs, have rolled out sabbatical programs in recent years. And some tech companies, like Adobe and Intel, have had policies in place for a while. Even so, sabbaticals are still a relatively niche perk. But it may just be a matter of time before they become mainstream.

What Is a Sabbatical Leave?

Sabbaticals in the modern workplace refer to extended paid breaks that long-tenured employees are given by their employers as a benefit or perk. But the concept’s roots are much older.

According to ancient Jewish tradition, people were to work continuously in the fields for six years. In the seventh year, they were to take a break. This sabbath year, as it was called, was considered a time of renewal and reflection.

The practice evolved in 1880, when Harvard University established the first sabbatical leave policy for faculty members, granting paid leaves to professors after their sixth year of employment. This policy came with the understanding that professors would return feeling refreshed and reinvigorated after spending time away from campus for research and study. The idea caught on, and by 1900, another nine colleges and universities across the United States had implemented sabbatical policies.

Types of Sabbatical Leaves

- Fully paid sabbatical: People are given their usual compensation during their time off.

- Partially paid sabbatical: People are given half or quarter base pay during their time off.

- Unpaid sabbatical: People remain employed with the company but are not paid during their time off.

Today, sabbatical programs are ubiquitous in higher education. According to a 2016 report by Sibson Consulting, 85 percent of the 450 colleges and universities surveyed offer their faculty fully paid sabbaticals. The median sabbatical leave was 20 weeks.

It’s difficult to pinpoint when exactly sabbaticals made the leap from college campuses to corporate HR policy handbooks. Some trace the first corporate sabbatical back to McDonald’s, which began in the 1960s and is still going strong, with eight weeks of paid sabbatical leave offered to full-time salaried employees who put in 10 years of continuous service.

No matter the context, it seems the defining features of any sabbatical are that it’s longer than a typical vacation, with a special emphasis on rest, rejuvenation or studies.

How Long Are Sabbaticals?

Sabbaticals in the corporate world usually clock in at four to six weeks. But some experts believe they should be longer.

“Ideally, sabbaticals are measured in months, not weeks,” said DJ DiDonna, an entrepreneur and founder of the Sabbatical Project, an initiative designed to spread awareness about the positive effects of sabbaticals.

While a month-long sabbatical is better than nothing, DiDonna said, it takes most people at least a month, if not two, to fully unplug and recover from their work routines and tap into the larger positive effects sabbaticals have to offer. For him, three to six months is the ideal length. Anything less than that is too short to unlock the benefits unique to sabbaticals.

“What a few months allows you to do is to step back from your normal, routine life and step into a different flow of life.”

In contrast to vacations, the average amount of which an American employee takes each year hovers around two weeks, sabbaticals are lengthy enough to provide the necessary distance from work for people to reflect on their identity and discover (or rediscover) their core values.

“What a few months allows you to do is to step back from your normal, routine life and step into a different flow of life,” said Lyndall Farley, who runs the sabbatical consultancy Beyond a Break. “And [that allows you to] shed the roles you have to play in your ordinary life ... and really get back to the essence of who you are.”

What Do People Do on Sabbaticals?

Sabbaticals look different for everyone. Some resemble stretched-out vacations, with plenty of rest and relaxation. Others are more structured and intentional, with volunteer or upskilling components laced throughout.

While working on the Sabbatical Project, DiDonna, along with University of Notre Dame research professor Matt Bloom, conducted a qualitative study of 51 people who took three-month-or-longer sabbaticals and reported their times away were life-changing. They noticed several overlapping ways people spent their time, including:

- Separation from work, both geographic and psychological, which often included travel.

- Participation in restorative activities, ranging from rest to exercise to play, where people intentionally rested and recovered from overwork.

- Enjoyment of adventuresome or novel experiences, like completing bucket-list goals.

- Reflection on identity and work, gaining perspective and asking questions about what they want out of life.

Ultimately, the itinerary of sabbaticals comes down to the length of the sabbatical and the season of life in which the sabbatical taker finds themselves.

During her six-week sabbatical, Buffer senior customer advocate Juliet Chen did whatever she wanted. Some days she practiced yoga and read a novel. On others, she took long walks or cycled along the coast. With the demands of her job out of sight, she was able to take each day as it came, unstructured and unhurried.

Barrett Brooks served as the chief operating officer of ConvertKit, an email marketing platform, for five years before he went on sabbatical. He designed his time to focus on the sorts of activities he enjoyed as a child, before the pressures of careerism crept in. So he built wooden models and LEGO sets and went on plenty of hikes, in addition to cooking a new meal recipe every week and spending quality time with his family.

Susie Chau, who now runs her own sabbatical program consultancy called Carpe Diem Traveler, negotiated a year-long unpaid sabbatical with her management consulting employer about a decade ago. The sabbatical allowed Chau and her husband to visit 22 countries and the space “to reflect on what’s important to me, how I want to live my life,” Chau said.

How to Prepare for a Sabbatical Leave

- Learn about your company’s sabbatical leave policy.

- Double-check that you can afford it.

- Ask yourself what you hope to get out of a sabbatical.

- Select a time frame for your sabbatical.

- Talk to your manager and HR about your plans.

- Finalize the plans in writing.

- Get your colleagues up to speed on responsibilities you own.

Benefits of Sabbatical Leave for Employees

Sabbatical leave offers employees a much-needed break from overwork, and it promotes creative, outside-the-box thinking that may lead to personal and professional breakthroughs.

1. Sabbaticals Reduce Burnout and Health Risks

Stressful work situations are associated with poor individual well-being and increased health risks. Long working hours lead to more deaths from heart disease and stroke, according to a joint World Health Organization and International Labor Organization study.

And vacations aren’t always enough to stave it off. Researchers found that, while burnout is reduced while people go on vacation, these feelings creep back up to high levels shortly after they return to work. Vacations may improve mood in the short term — but have no effect on long-term life satisfaction.

Sabbaticals, on the other hand, have been found to reduce stress and burnout and lead to higher levels of positive well-being.

2. Sabbaticals Encourage Creative Thinking

Something about extended time away from normal workday routines helps people think outside the box.

In his book Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less, workplace consultant Alex Soojung-Kim Pang observed that many important thinkers and innovators developed their seminal intellectual and creative ideas while away on trips and sabbaticals.

And while people often say they work best under pressure, that usually isn’t the case.

For a study whose results were published in a 2002 Harvard Business Review article, researchers collected thousands of diary entries from hundreds of employees across seven U.S. companies. They examined how people “experienced time pressure day to day as they worked on projects that required high levels of inventiveness, while also measuring their ability to think creatively under such pressure.” They concluded that, the more time pressure people feel, the less likely they will be to think creatively.

And with creativity often comes fresh ideas for the direction of one’s company. A 2009 report, for which 61 nonprofit leaders who took a sabbatical were surveyed, said sabbaticals gave many people a new vision for their work. Three-quarters of the leaders in the study found that the time away helped them “crystallize an existing vision for their organizations or frame a new one.” Nearly half of them later reported they had success in implementing their vision.

Benefits of Sabbatical Leave for Companies

Organizations want employees who are healthy, energetic, productive and creative. So all the reasons above apply to companies as well, not just individuals. After all, companies are made up of people.

In addition to keeping their workforce sharp and motivated, companies often implement sabbatical leave programs for two main purposes: recruiting new employees and retaining existing ones.

1. Sabbaticals Can Help Employee Recruitment

As a general rule of thumb, companies offering sabbatical leave to employees after only three to five years of continuous service do so as a recruitment tactic. It’s meant to attract potential job candidates who may be entertaining multiple offers. And in a job market where workers seek maximum flexibility in the workplace, sabbatical leave is a flashy, differentiating perk.

“Recruitment of the best employees has become increasingly important in every field,” noted researchers at Middle Tennessee State University. “Sabbaticals are proving to be a strong incentive for many top performers looking for workplace flexibility.”

2. Sabbaticals Boost Employee Retention and Morale

Some companies use sabbaticals primarily as a way to retain employees, rather than to recruit them. This is most evident in programs offering sabbaticals only to employees who put in six to 10 (or more) years of service. The idea here is that sabbaticals function as a reward for many years of hard work.

They’re also a way to boost the morale of employees who take them and can strengthen the bond between employees and their employers, which often incentivizes workers to stick around longer.

Dale Furbish, a senior lecturer at Auckland University of Technology, found that companies that offer employee-leave programs “gain the goodwill and revitalization of their workforce,” and “are viewed as employers of choice.”

Offering sabbatical leave can also “create a beautiful loyalty within the team,” said Courtney Seiter, vice president of people at Hologram, Inc. “Folks are really just blown away that you can provide a benefit like this.”

How Common Are Sabbaticals?

The number of companies with sabbatical programs remains relatively low. About 5 percent of organizations offer their employees paid sabbaticals (and 11 percent offer unpaid ones), according to a 2019 report published by the Society for Human Resource Management.

And yet, sabbaticals have earned a place in larger conversations happening among HR and people team circles. Companies big and small are trying to formulate the right benefits package that appeals to employees, many of whom have felt burnout and come to increasingly value employers that prioritize the mental health of their workers.

“Everything is up for grabs in the way that we work,” said Pang, who is also the founder of workplace consultancy Strategy + Rest and author of several other books on work-life balance. “The pandemic has shown that companies and individuals can change faster than we ever thought possible, and this opens the door to exploring and experimenting with all kinds of new ways of working.”

Carol Sladek, an Aon consultant specializing in time-off and work-life practices for Fortune 500 companies, said sabbaticals are “on the upswing in terms of interest.”

“Now, not all of them put one in place,” Sladek added, referring to the companies she consults. “But we did talk to a number of organizations in the last couple of years about this kind of program.”

Why Aren’t Sabbaticals More Common?

If sabbaticals are so good, why do only so few companies offer them?

1. Companies Fear the Costs and Risks

“It’s very costly to [offer sabbaticals],” Thomas Li-Ping Tang, professor of management at Middle Tennessee State University, said. “You have one person on the payroll but they’re not doing exactly what the company wants them to do.”

Aside from the concern of costs, when someone takes a sabbatical leave, workflows get interrupted too.

“If I’m out for six or eight weeks, something’s going to be missing,” Sladek said. “Either my work has to get shuffled to other people or I need to be replaced in some way.” This scenario is enough to spook some employers and send them searching for alternative perks their company can offer.

Some employers also refrain from implementing sabbatical programs for fear of a nightmare scenario: What if someone spends their sabbatical looking for a new job, and they quit when they return?

It’s a legitimate concern. But one that rarely happens in practice.

In the previously mentioned 2009 report, only 13 percent of organization leaders who returned from a sabbatical said the leave made them want to change jobs.

That’s not to say there’s no risk involved for organizations that offer sabbaticals to some of their employees. But in the aggregate, experts believe, the benefits outweigh the costs.

When you put sabbaticals in the context of how much it costs to recruit, hire and onboard new employees, “it becomes a no-brainer” for companies to offer sabbaticals to their employees, Farley said.

2. Employees Don’t Feel Safe Taking Them

Another, perhaps more overlooked reason sabbaticals aren’t mainstream is because, even when organizations permit employees to take them, the organizational culture is such that employees don’t feel psychologically safe to do so.

“The reluctance [to take sabbaticals is] based on the risk that employees have, the fear of being stigmatized, not just only by their supervisor, but also by their colleagues,” said Sarah Altmann, an academic teacher and researcher at Heinrich Heine University Dusseldorf whose research focuses on temporary leaves of absence and flexible working time practices. “There’s also the fear of having negative career consequences.”

And the concern is warranted. Researchers have found that people who take leave make less money, earn fewer promotions and receive lower performance reviews than colleagues who don’t take advantage of flexible work practices.

In U.S. work culture especially, there is a pervasive idea that time away from work — even to take care of family members — is damaging to one’s future job prospects. It’s a gap in the resume that threatens to derail or suppress one’s career. So, in the eyes of many, the idea of taking a sabbatical feels foolish.

Not only that, but workers are well aware that time off from work for them means heavier workloads for their colleagues. That work has to go somewhere, and it will likely be dispersed to other team members. Many workers in this situation can’t help but anticipate feelings of guilt. For some, it’s easier not to take too much time off than face the idea that coworkers feel extra stress from work because of their decision to take a sabbatical.

Companies That Offer Sabbaticals

While sabbatical leave isn’t a common benefit offered by companies, there are a handful of organizations, including legacy corporations and young startups alike, that are currently providing it to their employees. Here’s a non-exhaustive smattering of various companies’ sabbatical policies.

-

Adobe offers four weeks of paid sabbatical leave to employees who have been at the company for at least five years (employees with more tenure are eligible for longer sabbaticals).

-

Buffer offers six weeks of paid sabbatical leave to employees who have been at the company for at least five years (employees with more tenure are eligible for longer sabbaticals).

-

Citi offers up to 12 weeks of sabbatical leave, at 25 percent base pay, to employees who have been with the company for at least five years.

-

ConvertKit offers four weeks of paid sabbatical leave to employees who work for the company for at least five years.

-

Deloitte offers three to six months of sabbatical leave, at 40 percent of their base salary, for eligible employees (as well as one-month-long unpaid sabbaticals).

-

Drift offers four weeks of paid sabbatical leave to employees who have been with the company for at least three years.

-

Goldman Sachs offers six weeks of unpaid sabbatical leave to employees with at least 15 years of tenure at the company.

-

HubSpot offers four weeks of paid sabbatical leave for employees who have been with the company for at least five years.

-

Intel offers four weeks of paid sabbatical leave to employees after four years of employment with the company, and eight weeks to employees who choose to take their sabbatical after seven years with the company.

-

McDonald’s offers eight weeks of paid sabbatical leave to employees who work for the company for at least 10 years.

-

ProfitWell offers one month of paid sabbatical leave to employees who work there for three or more years.

-

Webflow offers five weeks of paid sabbatical leave to employees with five or more years at the company.

How to Create a Sabbatical Leave Policy

The precise duration and parameters around sabbatical policies vary across companies and industries. With no hard guidelines to follow, one frequently asked question among people leaders is: to what extent should the company suggest to people how they spend their sabbatical time?

Some Sabbatical Leave Policies Are Hands-Off

More often than not, the sabbatical leave policy is hands-off when it comes to how the employee wants to spend their time away from work.

Seiter, for instance, thinks employers shouldn’t dictate how workers spend their sabbatical time.

In 2019, Seiter helped establish Buffer’s sabbatical leave policy. The team discussed what level of involvement the company should have in suggesting how employees spend their sabbatical time. Ideas like mandating a volunteer component, or tying the sabbatical back to company values were considered, but ultimately, the sabbatical policy was implemented with no strings attached. Seiter believes they made the right call.

“I don’t think it’s the company’s business to tell someone what to do with the time off that they have been given,” Seiter said. “If you’re deep in the throes of burnout, maybe all you can do is watch Netflix all day for a couple of weeks. Maybe that is your coping strategy and the best you can do right then.”

Some Sabbatical Leave Policies Are Structured

On the other hand, Farley, the sabbatical consultant, says it’s a mistake when companies neglect to help workers with how they might structure their sabbaticals. Several months without a plan can be daunting for many people, and most could use some sort of guidance on how to approach their time away.

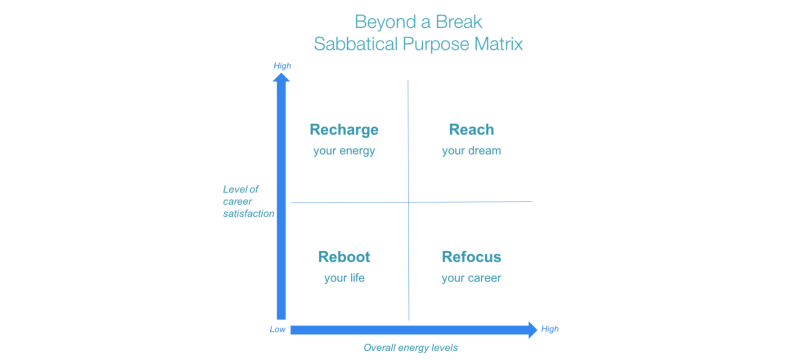

That’s why Farley recommends organizations use a sabbatical matrix (pictured below) when working with employees who take a sabbatical. Depending on the person’s level of career satisfaction and overall energy levels as they head into sabbatical, they may want to focus their time on certain activities.

For instance, if they love their job but are feeling burned out, they may want to concentrate on getting good rest and practicing restorative activities, such as exercising, working with their hands and reading by the beach. For someone who loves their career and is full of energy, the sabbatical might be a good time to climb Mount Everest.

Companies that present employees with this framework may spare them from the pressure-filled experience of staring down a blank canvas when their sabbatical begins.

How to Create a Sabbatical-Friendly Culture

Sabbaticals offer many benefits to both organizations and employees alike, but those benefits are only accessible when employees actually take them. So how can workplaces make sure that happens?

Organizations can combat the pervasive, fear-based thinking around taking extended time away from work by not only implementing a formal sabbatical policy and program, but also by establishing and maintaining a culture that actively and consistently celebrates when people take sabbaticals.

It’s easier said than done. But Farley suggests having the company’s CEO take a sabbatical first. That often catches people’s attention and helps to take some of the stigma out of the practice.

Next, Altmann said, organizations should encourage managers to take the initiative and suggest the idea of taking a sabbatical to their direct reports. Whether a coworker is burning out or pining to realize a personal dream, when the manager floats to them the idea of taking a sabbatical, it often feels like they’re receiving permission that wasn’t totally there before. And it makes them feel safer about taking one.

Overall, the internal communication around sabbaticals is important. Leaders have to market the perk within the company, and acknowledge that employees not only need to be rewarded for their hard work, but require ongoing breaks.

“It’s generally rolled out as a big bonus,” Sladek said. “It’s intended to budge that culture a little bit in the direction of recognizing that people do need time off.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Who qualifies for sabbatical leave?

Employees may qualify for sabbatical leave after working a specific amount of time at a company that offers the benefit, usually at five or more years.

However, an employee's qualification for sabbatical leave will depend on each company's own sabbatical leave policies.

Do you get paid on sabbatical leave?

Whether or not you get paid on sabbatical leave will depend on the company offering the benefit. Some companies offer fully-paid or partially-paid sabbatical leave, while other companies only offer unpaid sabbatical leave.

Are there downsides to sabbatical leave?

There can be downsides to sabbatical leave for both employees and companies.

For employees, a sabbatical leave may negatively affect salary, promotion eligibility or performance review results.

For companies, providing sabbatical leave can be a costly investment and disrupt workflows for other employees.