Concrete is in our sidewalks, our patios, our pool decks. It supports our skyscrapers and shapes our fountains. Concrete is, quite literally, the building block of modern civilization. Look closely, though, and you’ll see — it’s also choking our atmosphere.

Each year, the production of cement (concrete’s key ingredient) emits more than two billion tons of CO2, or about 8 percent of global CO2 emissions, which exacerbates climate change.

The global population — and urbanization — are on the rise, and the demand for construction projects is expected to rise with it.

If we continue to build up our infrastructure with concrete, will the planet be able to survive the resulting emissions?

Some companies would rather not find out the hard way. They are busy experimenting with cement chemistry and blazing a path toward sustainable concrete manufacturing.

Changing a Centuries-Old Process

Cement, also called Portland cement, has been around for centuries. Traditionally, it’s made by heating up limestone and clay in a kiln. During that process, limestone turns into lime (not the citrus fruit). The stuff that emerges is ground up and mixed with other minerals, then it’s cement.

The heating part — the lime-making part — is what causes the bulk of cement’s CO2 emissions, and that’s the nut Solidia Technologies worked hard to crack.

About a decade ago, Nicholas DeCristofaro, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology-trained material scientist, joined Solidia in Piscataway, New Jersey, to serve as chief technology officer and help commercialize a new cement solution — one that would be just as structurally useful, but not as environmentally harmful, as Portland cement.

The team licensed a chemical process from Rutgers University and got to work. After two years of testing, Solidia was able to successfully make a cement that emits 30 percent less CO2.

They achieved this by using more clay, less limestone and less heat than the traditional process.

You would think that modifying a tried-and-true, centuries-old formula would have its drawbacks. (Would I feel safe walking on a bridge made of alt-cement, for example?) But DeCristofaro says Solidia cement is just as good — and even better, in some regards — than Portland cement.

For example, concrete typically takes about three to seven days after it’s poured to reach a useful strength. Solidia-cement-based concrete, however, reaches its final hardness in less than 24 hours.

Is Alternative Cement Too Disruptive?

Getting the science right is enough of a challenge. After that, though, there are even more hurdles to clear.

The industry’s gatekeepers — corporations and academics that govern cement and concrete codes — often view disruptive technologies with skepticism. After all, nobody wants to be put out of business.

“If we’re threatening cement companies, they are going to be very reluctant to approve codes on new materials,” DeCristofaro said.

Solidia, then, strategically positioned itself not as a threat but as a natural partner to existing cement stakeholders. Its product is still compatible with longstanding cement plants and can be used to make the same old concrete building blocks we see everywhere. “We’re disruptive in terms of the science,” DeCristofaro said, “without necessarily being disruptive in terms of the business.”

“We’re disruptive in terms of the science, without necessarily being disruptive in terms of the business.”

Solidia has qualified as a Portland cement substitute for ready-mix cement (which represents about 70 percent of the cement market) in a number of U.S. research labs, according to DeCristofaro, who said the company’s science has been proven and practiced on an industrial scale in North American and Europe.

Solidia is already further down the commercialization path with pre-cast cement, which is made in a factory. For that process, the company carbonates cement after it’s put in the concrete, totally replacing Portland cement. DeCristofaro says there are multiple factories already manufacturing this material for sale, and it’s already being used for landscape-hardscape.

It will take time, though, before this becomes commonplace. Cement companies are not going to adopt new products overnight.

“Unfortunately, with codes and specifications, we can’t just snap our fingers and expect the world of Portland cement to transition to Solidia cement,” DeCristofaro said. “It’s going to be some kind of evolutionary process. It’s our job to make it as fast as possible.”

Growing Cement From Scratch

Not all companies on the alternative cement scene are content fiddling with the existing formula. Some are throwing out the old rulebook and starting from scratch.

Take BioMason, a Raleigh, North Carolina-based startup that’s also bent on reducing CO2 emissions. BioMason’s cement-making process skips the heating process altogether; instead, the company grows bricks and masonry — from bacteria.

It all started when BioMason’s co-founder and chief executive, Ginger Krieg Dosier, was thinking about coral reefs. An architect by trade, she marveled at nature’s enviable ability to produce strong, durable structures safely and organically. One day she wondered, why can’t we?

“Why is Portland cement a problem? Is there a way to rethink this?”

Ginger checked out stacks of books from the library across the street, turned her family’s second bedroom into a lab and experimented with various microorganisms. She eventually replicated a coral reef formation and ended up with a 1:10 scale masonry unit to show for it.

Ginger and her husband Michael, the company’s co-founder and chief technology officer, moved production from their spare bedroom to a proper facility. There, they and the rest of BioMason’s team have been building their home-brewed cement into a viable business.

The BioMason process involves forming bricks of loose aggregate and inoculating them with a strain of bacteria. Then, calcium carbonate grows in the gaps. In just three days, a cement-like brick emerges.

The final product’s ingredient list is simple: It’s about 85 percent waste aggregate and 15 percent biologically grown calcium carbonate.

Other alternative cements emit less CO2. BioMason’s process, though, makes cement without releasing any. “We’re not adding in a little bit of Portland, we’re not injecting CO2 into it,” Ginger told Built In. “It’s honestly a very, very fast way to make cement the same way that it’s made in marine environments.”

They know it’s ambitious. But they didn’t want to just reduce CO2. They wanted to eliminate it.

According to Michael, “We wanted to go back to the very beginning of the chain and say: ‘Why is Portland cement a problem? Is there a way to rethink this?’”

What Can’t Bacteria Cement Do?

BioMason is well aware of the stakes, and that bacteria cement can be a tough sell. “We knew from the start ... we’re making a material that has to perform as well or better than existing materials,” Michael said. “So in about three days, we’re able to go from loose sand to a solid unit that’s outperforming other products on the market.”

BioMason makes its product twice as strong as a typical concrete block needs to be. For example, BioMason blocks have a compressive strength exceeding 4,500 PSI. (The minimum a concrete block is allowed to withstand is 1,700 PSI.)

Even though BioMason knew how to make its product strong, it also needed to make it scalable. “We’re talking about concrete, so we’re talking about a colossal amount of material that’s made in the plant,” Michael said. “We’ve got to be able to make tons of it.”

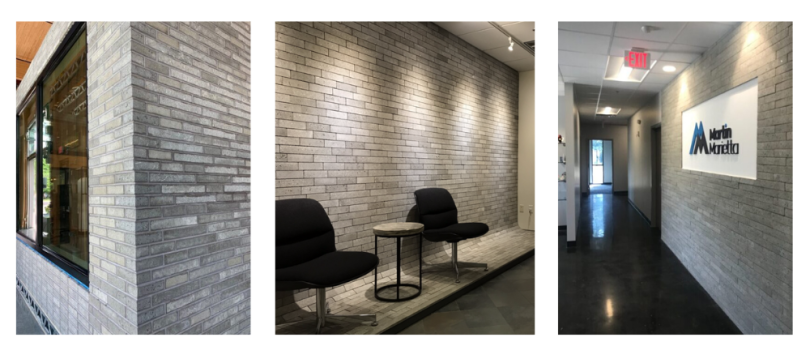

Today, BioMason produces tile products that can be used both horizontally and vertically, outside and inside.

“That’s been an incredible adventure,” Michael said. “Going from what was simply an amazing proof of concept in a laboratory, to creating a pilot plant that can actually produce these materials in a technology that’s scalable to be able to start to compete in the building materials industry.”

Last year, the two co-founders were busy putting on a few demonstrations for investors, and they built a full-scale mock-up inside an innovation lab with HITT Contracting. You can already see some of their product out in the wild too: In 2015 they delivered their first order to Dropbox’s San Francisco headquarters.

Can Alt-Cement Make a Big-Enough Impact?

Companies have been trying to make viable, alternate cements for decades. But it’s been difficult for many to get any market traction.

Relative newcomers like Solidia Technologies and BioMason (as well as Canadian cement startups such as CarbonCure and Carbicrete) are helping a historically slow-moving industry take needed steps toward sustainability.

Will their endeavors, however well-intentioned, amount to anything more than just a drop in the bucket? Is alternative cement enough to make a difference on a global scale, to slow down CO2 emissions in a meaningful way?

“Much of whether it happens or not will probably be political.”

Solidia’s DeCristofaro believes that we’re well on our way to halving the industrial CO2 output by 2030 and being carbon neutral by 2050. However, “much of whether it happens or not,” he caveats, “will probably be political.”

“I think that it is a long road,” Biomason’s Ginger said. “We’ve always thought of what we’re doing at BioMason as creating a whole new industry. So there’s a lot of steps to get to making that significant impact.”

Sometimes, though, the long road is the best path.

“We’ve certainly expanded our brains quite a bit in the past few years really looking at a 50- or a 100-year forecast in terms of what’s available on the planet to be able to make this technology,” Ginger added. “It’s actually really more of a thought process to identify where we are going as a global society.”