Born in Egypt, Farrah wears a hijab and pink, slip-on flats. She speaks Arabic at home. Her mother doesn’t speak English, but Farrah learned it quickly after immigrating to the United States at the age of seven. She’s proud of her accent and confident speaking about her interests: nature, biology and wildlife.

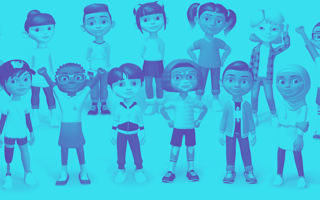

Like the other 16 animated characters in Rosetta Stone English, an adaptive learning program for emergent multilingual students, Farrah’s life and identity are well drawn. She is an iconic representation of a multilingual student whose complex cultural heritage and multidimensional personality make her relatable — and, thus, part of a powerful model for language acquisition.

“If you’re going to learn another language, you have to have some sort of motivation,” said Maya Goodall, senior director of English curriculum at Rosetta Stone. “Maybe you’re going to travel, maybe it’s for a job, maybe you fell in love. So, in our case, we’re treating these as friendships. These characters are your friends. They’re also learning English themselves.”

More than 10 percent of the nation’s public school students are English language learners (ELL), and, according to 2013 U.S. Census Bureau data, 85 percent of ELL students in pre-kindergarten to 5th grade were born in the U.S.

For many students, learning to speak and interpret academic English is an uphill battle, in part because many of the books and online tools instructors use to teach English fail to represent their ethnic or cultural identities, or treat students’ heritage languages and cultures as deficits to overcome, rather than assets to build upon.

“We’re treating these as friendships. These characters are your friends.”

Meanwhile, as more students move to distance learning environments due to the COVID-19 pandemic, inequities in the school experiences of English language learners have become more pronounced.

“Before, every classroom had its own door, and it could be closed, and the teacher and the students were there together, and what was happening may or may not be known to others,” Goodall told me. “Now, it’s very clear that certain methodologies and certain ways of doing things — whether it’s teaching language, teaching reading, anything — we have to confront those disparities.”

Rosetta Stone English, launched in August of 2020, attempts to address education gaps by employing culturally diverse characters with distinct speech patterns. Led by Goodall and Kristie Shelley, also a senior director of English curriculum, an 18-person team comprising designers, writers, developers and engineers spent 18 months creating distinct storylines and 3D visual identities for each character — from Annie, a surfer with an artificial leg who was born in Vietnam, to Juan, a first-generation Mexican American who has diabetes and wears an insulin patch.

Guiding the program are three foundational principles.

Asset-oriented multilingual model

- The first language a learner knows is treated as an asset.

- Multilingualism is a valued attribute. All characters speak their heritage languages and have accents reflecting their personal linguistic histories.

- Diverse cultures and identities are valued and seen as educational resources.

Where language learning apps like Duolingo and Babbel focus on conversational English, Goodall told me, Rosetta Stone English directs its lens at academic English: the formal grammar, style and usage taught in many U.S. schools. Because learning these rules can be tedious, UX design became important to fostering engagement — and character identification is key.

Identification Versus Stereotyping

In the article “Defining Identification: A Theoretical Look at the Identification of Audiences With Media Characters,” Jonathan Cohen, a researcher at University of Haifa, notes that, “when reading a novel or watching a film or a television program, audience members often become absorbed in the plot and identify with the characters portrayed. Unlike the more distanced mode of reception — that of spectatorship — identification is a mechanism through which audience members experience reception and interpretation of the text from the inside, as if the events were happening to them.”

This type of vicarious experience can create aspirational models of behavior for students to emulate and increase the likelihood they will pay attention to the information presented, according to Cohen. But while diverse character representations can support learning and heighten students’ cultural and emotional awareness, they can also be misapplied in offensive caricatures.

Several years ago, for instance, performers including Hari Kondabolu, Kal Penn and Aziz Ansari criticized the portrayal of the Simpsons character Apu for being racist and perpetuating stereotypes.

“This character — the only representation that we have — led a lot of kids who were born and raised here to feel non-American,” Kondabolu told an Associated Press reporter in a 2017 interview.

Population Research and Cultural Representation

Rosetta Stone sought to avoid such problematic portrayals.

To build an accurately representative sample of characters, the design team evaluated the percentage distribution of English language learners in U.S. public schools by their home languages, as reported by the National Center for Education. Spanish/Castillian is the most frequently cited home language, representing nearly 75 percent of all ELL students, followed by Arabic (2.7 percent) and Chinese (2.1 percent).

“We started by researching the student population that we’re serving to see what languages are spoken and what countries students originated from,” Shelley said. “That helped us build the cast of characters, in a few words — what we were going to be expressing to those students on screen.”

These percentages helped the team reflect real-world data. To appeal to international students, the team included characters who live outside the U.S. and are learning English.

“We started by researching the student population that we’re serving to see what languages are spoken and what countries students originated from. That helped us build the cast of characters, in a few words.”

The project’s writers — all multilingual and with expertise in applied linguistics — developed detailed biographies describing characters’ countries of origin, current residences, ages and family dynamics. These bios became the basis for user-journey templates describing how learners would progress across 19 levels. The characters evolve over time, and biographies of diverse historical figures are also woven into the program.

“We wanted the learners to see themselves reflected like a mirror. And then we also wanted them to have windows to see who they might become and who they are becoming,” Shelley told me.

Assimilation Versus Acculturation

But overcoming ingrained industry-wide practices is not easy to do, especially in the context of animation, where physical features and accents have often been exaggerated for stylistic effect or thematic emphasis and characterizing traits have often sprung from stereotypes.

To avoid this, the writers coordinated closely with the graphic design and illustration team, meeting three times each week to ensure the visual representations of characters and their speech patterns were authentic and promoted a positive attitude toward language acquisition. In addition, the entire design and development team attended a culturally responsive pedagogy training, and actors hired to speak the characters’ lines were chosen, in part, because of their abilities to speak the same heritage languages as the characters they represented.

Design reviews were framed by acculturation — the belief that the preservation of an individual’s heritage language and culture enrich the national identity — over assimilation, which Gooddall defined as “the idea we’ve all grown up with, which is the United States as a melting pot. So you come to the United States. You shed your first language, you shed your heritage culture, you shed who you were before, and you come and melt into something new.”

While regionally specific elements of American life — like Annie’s interest in surfing — are woven into the narratives, they do not efface characters’ cultural identities, and they are balanced against interests more squarely rooted in each character’s cultural history.

“So you will see, for example, Serena meets a friend, and they take dance lessons together from an Indian dance school,” Shelley said.

Phoneme Sensitive AI

Over the past 25 years, Rosetta Stone’s speech recognition engine has evolved to detect subtle nuances in the speech patterns of learners using the software, Shelley told me.

“Instead of letting AI infuse unconscious bias into [the learning process] without even thinking about it, we really wanted to take a step back and see how we could build equity back into it,” she said.

By detecting distinct phoneme blends of the 13 languages spoken by the characters, the speech recognition engine can intimate the intended word choice of speakers whose first language does not have a comparable sound in English. The “sh” sound in English, for example, doesn’t exist in Spanish, but can be approximated by a harder “ch” sound — which the software’s speech engine detects from the context of the sentence.

“Instead of letting AI infuse unconscious bias into [the learning process] without even thinking about it, we really wanted to take a step back and see how we could build equity back into it.”

“If [Spanish-speaking English language learners] want to say the word ‘share,’ as in, ‘Can you share some candy with me?’ they’ll often say, ‘Can you ‘chare’ some candy with me,” Shelley explained. “They can generally eventually work [the “sh” sound] into their repertoire. But the speech recognition engine will be trained to be able to take that phoneme blend in context and say, ‘OK, we’ll accept that pronunciation, because we know that some people will pronounce it that way.’”

The characters themselves speak with accents that are presented as sources of pride, not deficits to overcome. Moreover, they toggle between English and their first language to mirror the type of language switches that naturally take place among English language learners.

“We wanted to make this very universal,” Goodall said. “So as you listen to the characters talking, you’ll hear a little accent, because we wanted to reflect their lives and say, ‘Hey, no matter how you speak English, it’s OK.’”

As of November, Rosetta Stone English reported 7,500 enrolled students and was adding roughly 1,000 per month. If the program is as successful as Goodall hopes, it may help chart the course for culturally sensitive approaches to online animation and reframe how schools treat English language learning — not as a skill that can be absorbed solely through immersion, but a subject in its own right.

“There was definitely a time when an educator might think to themselves: ‘Hey, I’m teaching in English all day. I’m teaching reading in English, I’m teaching science in English, this is immersion. And the learner should learn English,’” Goodall said. “And now without that experience [due to distance learning], they have space to confront that and realize, actually, that’s not how a person learns, just through immersion alone.”