Recursion in SQL? But why? Oh, there are many uses for that. It’s common to store hierarchical data in SQL and recursive queries are a convenient way to extract information from such graphs. Some common examples of hierarchical data you might encounter include organizational structure, application menu structure, a set of tasks with sub-tasks in the project, links between web pages and a breakdown of an equipment module into parts and sub-parts.

What Is a Recursive SQL Common Table Expression (CTE)?

A recursive SQL common table expression (CTE) is a query that continuously references a previous result until it returns an empty result. It’s best used as a convenient way to extract information from hierarchical data. It’s achieved using a CTE, which in SQL is known as a “with” statement. This allows you to name the result and reference it within other queries later.

The post will not go into the details of those many use cases, rather it will examine two hypothetical examples designed to help you understand the concept — the simplest possible case of recursion in numbers and querying data from the family tree.

Recursive SQL: What Does It Mean and How Does It Work?

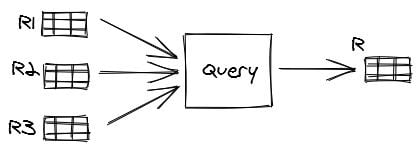

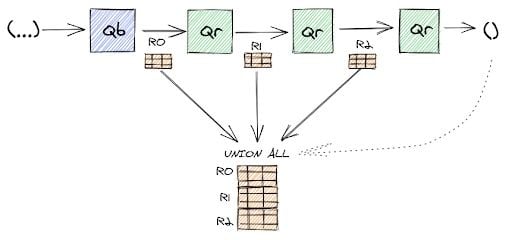

Let’s think about queries as a function in the sense that a function takes an input and produces an output. Queries operate on relations, or one could say tables. We will denote those as Rn. A query takes three relations — R1, R2 and R3 — and produces an output R. Simple enough.

SQL example: SELECT FROM R1, R2, R3 WHERE.

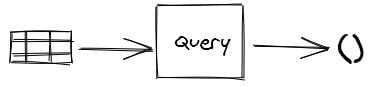

A query can take something and produce nothing:

A visual representation of a query taking something and producing nothing. | Image: Denis Lukichev

SQL example: SELECT FROM R1 WHERE 1 = 2

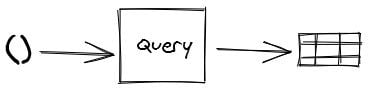

It can take nothing and produce something:

SQL example: SELECT 1.

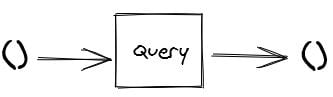

Or it can take nothing and produce nothing.

SELECT 1 WHERE 1 = 2

How to Write a Recursive Common Table Expression (CTE) in SQL

Recursion is achieved using a WITH statement, which in SQL jargon is called a common table expression (CTE). It allows you to name the result and reference it within other queries later.

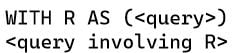

Here is a sample.

WITH R AS (SELECT 1 AS n)

SELECT n + 1 FROM R

Query (SELECT 1 AS n) now has the name R. We refer to that name in SELECT n + 1 FROM R. R is a single row, single column table containing number one. The result of the whole expression is number two.

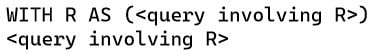

The recursive version of the WITH statement references itself while computing the output.

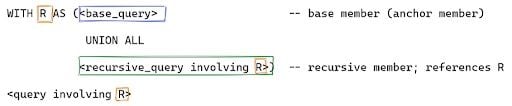

For the recursion to work, we need to start with something and decide when the recursion should stop. To achieve this, a recursive with statement typically has the following form:

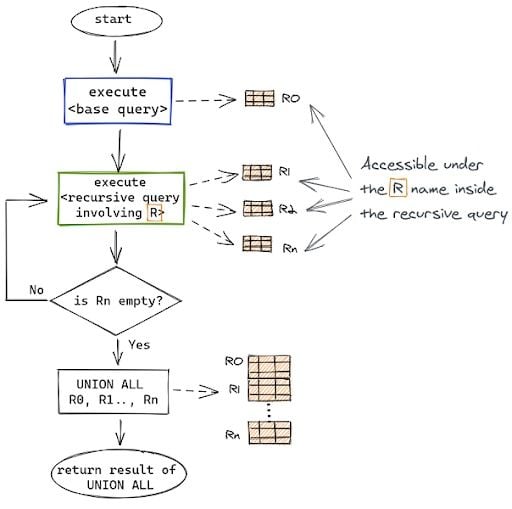

It’s important to note that the base query doesn’t involve R, however, the recursive query does reference R. At first glance, it seems like an infinite loop. To compute R, we need to compute R. But there’s a catch. R doesn’t reference itself, it just references the previous result. And when the previous result is an empty table, the recursion stops. It might help to think of it as an iteration rather than a recursion.

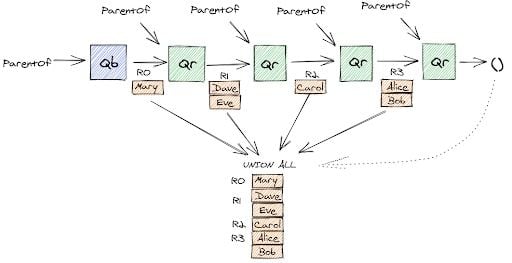

Here’s what happens. The base query executes first, taking whatever it needs to compute the result R0. The second recursive query is executed taking R0 as input — that is R references R0 in the recursive query when first executed. The recursive query produces the result R1, and that is what R will reference at the next invocation, and so on until a recursive query returns an empty result. At that point, all intermediate results are combined together.

Recursive SQL Examples

If that’s too abstract, let's look at a couple concrete examples.

Example 1: Count Up Until Three

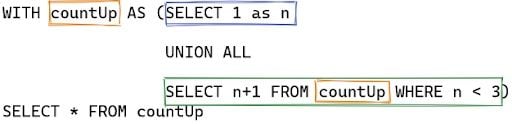

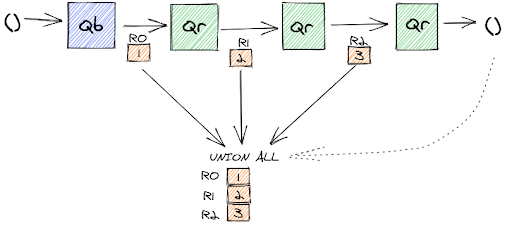

The first example we’ll explore is count until three.

The base query returns number 1, the recursive query takes it under the countUp name and produces number 2, which is the input for the next recursive call. When the recursive query returns an empty table n >= 3, the results from the calls are stacked together.

Counting up like that, however, can only go that far. There is a limit for recursion. It defaults to 100, but it could be extended with the MAXRECURSION option (Microsoft SQL Server specific). In practice, however, it could be a bad idea to crank the recursion limit up. Graphs might have cycles and limited recursion depth can be a good defense mechanism to prevent a poorly behaving query: OPTION (MAXRECURSION 200).

Example 2: Finding Ancestors

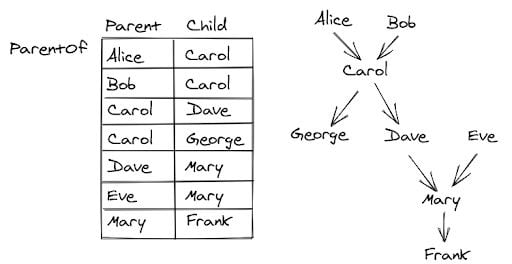

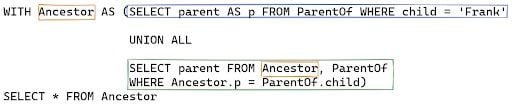

Let’s look at another example, finding a person’s ancestors.

The base query finds Frank’s parent, Mary, and then the recursive query takes this result under the Ancestor name and finds Mary’s parents, who are Dave and Eve. This process continues until we can’t find any more parents.

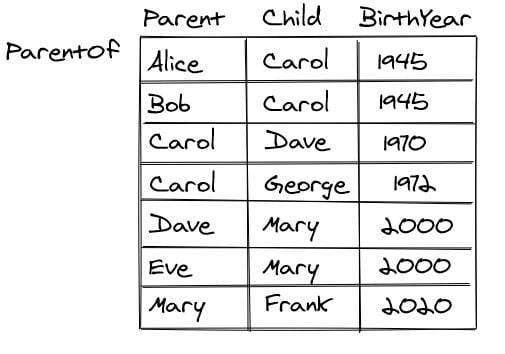

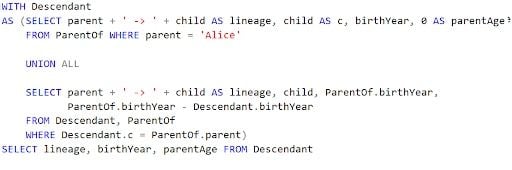

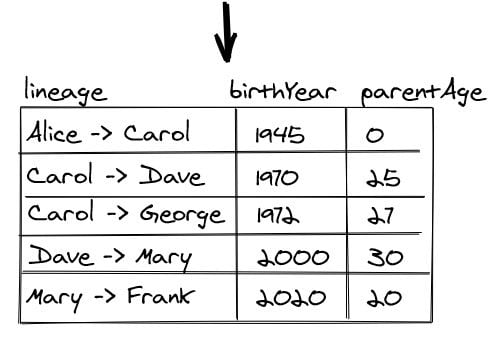

This tree traversal query could be the basis from which you augment the query with some other information of interest. For example, having a birth year in the table, we can calculate how old the parent was when the child was born. Our next query can do exactly that, along with showing lineages. To do that, it traverses the tree from top to bottom. parentAge is zero in the first row because we don’t know when Alice was born from the data we have.

The takeaway is that the recursive query references the result of our base query or a previous invocation of the recursive query. The chain stops when the recursive query returns an empty table.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is CTE in SQL?

A common table expression (CTE) in SQL is a temporary named result set in an SQL query. CTEs exist within the scope of a larger SQL query, and can be defined and referenced within a SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE or DELETE statement. A CTE is also able to be referenced multiple times, making it helpful for organizing complex queries and extracting hierarchical data.

How to have multiple CTEs

In SQL, multiple CTEs can be written in one query by using a comma to separate each. For example:

WITH cte1 AS (

SELECT column1

FROM table1

),

cte2 AS (

SELECT column2

FROM table2

)

SELECT *

FROM cte1

JOIN cte2 ON cte1.column1 = cte2.column2What is a recursive query in SQL?

A recursive query in SQL is a query that calls itself continuously until no new result is found. A recursive common table expression (CTE) in a query, for example, repeatedly references a previous result until it returns an empty result. Recursive queries are often used to handle hierarchical data and help navigate hierarchical relationships in a database.

What is the difference between a base query and a recursive query in a CTE?

The base query generates the initial result set without referencing the CTE name. The recursive query then references the CTE to build upon that base, iterating until the result is empty.