There was a huge uproar in the press in July 2009 when I was appointed chief executive officer of Xerox: the headlines proclaimed that I was the first Black woman to lead a Fortune 500 company and that for the first time the CEO mantle had been passed from one woman, Anne Mulcahy, the outgoing CEO, to another. What a ridiculous way to make history. Though both headlines were factually correct, the press missed what was a unique story: How did this happen? How is it that the Xerox Corporation had two female CEOs, one after another? How did the Xerox Corporation produce the first African American woman CEO? That should have been the conversation, not these ridiculous stories proclaiming, “Oh my god, not one but two women” and “Oh my god, a Black woman made it.” Was it truly so amazing to think a Black woman could lead a multibillion-dollar company? I had worked at Xerox for twenty-nine years by then. I had a strong track record. I was very well educated. I hadn’t been plucked from a circus sideshow. I had earned the position.

In that instant, I joined the top five hundred business leaders in the United States out of a population of 306.8 million. That is 0.000163 percent of the total population. And the repercussions were immediate.

Was it truly so amazing to think a Black woman could lead a multibillion-dollar company?

I got congratulatory calls or emails from at least a hundred other CEOs and from high-profile African Americans. I heard from my good friend and mentor Vernon Jordan, the corporate titan and adviser to President Clinton, and from Ken Chenault, the chairman and CEO of American Express, on whose board I sat. I also received congratulations from many others I didn’t know, like the civil rights leaders Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson and the basketball legend Magic Johnson, himself the CEO of the $1 billion Magic Johnson Enterprises. I got phone calls from US senators and members of Congress, and practically every company and nonprofit in the country asked me to join their boards. How many commencement addresses was I asked to make? How many speaking engagements? How many media interviews? My teenage daughter, Melissa, was unimpressed. “The phone’s for you,” she told me that night. “I think it’s a newspaper or something.”

The enormous amount of attention continued for days. I was at our home in Rochester, a midsize city in upstate New York and the manufacturing and engineering headquarters for Xerox at that time. Everyone knew everyone else, so there were smiles and congratulations on the street and in the grocery store and in the dry cleaner’s every time I left the house. There were paparazzi too. It was impossible for me to be unaffected. I’d made it. I’d arrived. I felt terrific but also apprehensive. I was not becoming the CEO of Apple. I was becoming the CEO of Xerox, which had gone through two or three near-death experiences by then. The company had to be led, to be managed, to be strengthened, and it was not going to be an easy ride. Xerox needed a lot of work, and I quickly returned to the company’s nondescript executive headquarters in Norwalk, Connecticut.

Taking the Reins During the Great Recession

My promotion to CEO came at a perilous time for the US and global economy. The year 2009 saw the end of George W. Bush’s administration and the beginning of Barack Obama’s, an election that brought a lot of joy but occurred during the most dangerous economic time since the Great Depression. The country was slowly beginning to recover from the 2007–2008 global recession, which had been precipitated by excessive risk-taking by banks, the failure of the investment bank Lehman Brothers, and the imminent collapse of the auto industry. Detroit declared bankruptcy, the stock market tanked, and all over the country many people lost their jobs and homes. It was an unbelievably bad time for the economy and for every US company, including Xerox.

The company had to be led, to be managed, to be strengthened, and it was not going to be an easy ride.

The US government was one of our largest customers, along with the banking and auto industry. Xerox faced a heightened risk of bankruptcy because those sectors were so strained that payments were delayed indefinitely. Xerox was primarily a business-to-business (B-to-B) company, which means that we sold to other businesses, unlike business-to-consumer (B-to-C) companies like Proctor & Gamble or Nestlé, which sell many of their products to end consumers. As the world economy slowed down, our business slowed down, everybody’s business slowed down. Spending was tightened around the world, and optimism was low.

My Most Expensive Meal

The dinner for four in Dallas cost Xerox $6.3 billion and was extraordinary. The guest of honor was Lynn Blodgett, CEO of Affiliated Computer Services (ACS). Dining with Lynn were Larry Zimmerman, Xerox’s CFO; Anne Mulcahy, the outgoing CEO of Xerox and board chair; and me, the incoming CEO. On the table was the potential purchase of Blodgett’s company, which would allow Xerox to transform itself from the business machines company that had defined photocopying for decades into a provider in the newer, lucrative world of business services.

We had to diversify for Xerox to grow.

Xerox was operating in an industry with built-in technology-driven irrelevance. For all the brilliance of our machines, the move to digital picture frames and devices like smartphones reduced the need to print photographs and documents. We still generated $2 billion in cash annually, but looking down the road the traditional market for Xerox would continue to shrink without diversifying. That’s why we were having dinner with Lynn Blodgett.

He was sizing us up, and we were sizing him up. It wasn’t necessary that we “love” him, but it would have been really difficult if we didn’t like him at all.

Anne and I were meeting Lynn for the first time. Larry already knew him, having spent months getting us to this point. It would be a huge deal for Xerox if we could work out at least an understanding with Lynn on the path forward. The two small business services companies we already owned—one in legal services, the other in mortgage services—were a good start in our strategy to diversify, but it would take years of similar small acquisitions to reach the desired size, and here was ACS, an established and profitable company in business process outsourcing that already had most of what we wanted.

Companies were already embracing business process outsourcing in areas such as information technology, payroll services, security services, and processes like legal discovery. ACS was the only company that had different business processing capabilities under one roof. If we could work out a deal with Lynn, Xerox would be positioned for the future.

Conversely, we had what Lynn wanted: the Xerox brand, which meant reliable, innovative quality and service, along with a set of technologies that ACS could apply to their business to increase efficiency. And Xerox could help ACS expand its reach around the globe, which would be good for the US-centered company. We chatted at dinner about our two companies and whether we would be a good match. He was sizing us up, and we were sizing him up. It wasn’t necessary that we “love” him, but it would have been really difficult if we didn’t like him at all. In business terms, “love” and “like” are about the cultural fit. “Love” would require that Lynn have the same goals we had, the same moral approach, the same lingo, and the same company culture and also be brilliant and successful at business. “Like” would mean that there might be a couple of things that are not exactly ideal, but none of the important things. As dinner progressed, Anne and I decided we both liked Lynn a lot. He was important to the deal, and we wanted him to stick around for the first twelve to eighteen months at a minimum. Was he willing?

We had a green light from Lynn by the time we got to coffee. Anne and I felt that this consolidation was something that could work, that it was worth going forward. We both knew it would require a significant but manageable effort, and we were willing to accept the risks inherent in buying an already running entity. One risk arises from merging employees from various new geographical locations. Another is the potential hidden bombs you might find in the company. As much as you spend on due diligence, until you own the company you never know all the details. The seller, quite naturally, has only shown you the best. The third risk is what is called “change of control” provisions. Both of our companies had signed contracts with many clients, and Xerox would have to get agreements from as many ACS clients as possible before closing. And the risks don’t stop there. Some shareholders won’t want the purchase to go through. Some shareholders will think you paid too much, while the other side will think you paid too little. And then there’s the government, which might want you to sell a division or two for anti-monopoly reasons. The road ahead had many potholes. Still, I was very excited about the consolidation, though wary about the amount of work it would take to be successful.

I was right.

Ironing Out the Details

The project kicked off at the same time I became CEO and was a huge distraction to what would have been the normal first six months of a new CEO. Instead of holding town halls with Xerox employees or visiting customers or working with my team or cleaning up the ramifications of my physical move, I basically handed the day-to-day operations over to my management team while I worked with Larry Zimmerman and our general counsel, Don Liu, on the details of the still-secret negotiation with ACS. We wanted to sew it up before the business community caught wind of it, which ended up requiring two months of daily, hourly, minute-by-minute phone calls and meetings on weekdays, weekends, early mornings, and late nights.

Most calls regarded financial issues, but other issues presented themselves: whether ACS could keep their plane, whether we were going to assume more of ACS’s debts, whether we were going to leave individuals in certain positions. One challenge was negotiating with Darwin Deason, a major stockholder and the company’s founder. He owned preferred stock, which entitled him to special voting rights. He owned 25 percent of the ACS shares, but every one of his shares could vote twice in any decision. ACS also provided him with certain services, like his own plane, which we would have to buy out or accommodate.

At times, accusations of broken commitments from both sides led to consideration of calling off the whole deal. At other points, we were really close to an agreement but then Don would call and say, “We’re in a pens-down moment.” The drama continued until we finally struck a deal with ACS in September 2009, two months after I had become CEO, and both our boards approved it. We scheduled the public announcement for Tuesday, September 29, at eight in the morning, followed by press interviews at nine, but then we heard from sources that somebody, probably a banker, had leaked the story to the press. This was bad news. We didn’t want Xerox stock to be traded before the news of the ACS purchase was made available to the general shareholders. We had an emergency conference call and hurriedly moved up the date to September 28, which created another problem. I did not realize that the 28th was the Jewish religious holiday of Yom Kippur, and Xerox was roundly criticized for disrespecting the holiday. I felt terrible about it and apologized on the many press calls that morning, but there was nothing we could do. And the next round of negotiations began, this time with our major shareholders who had yet to vote on the acquisition of ACS.

Selling the Deal to the Shareholders

I met with Marvin Schwartz in the maze of offices at Neuberger Berman, the famous New York investment company that was a major shareholder in Xerox, and it was intense. He is very smart, with an extraordinary and long track record of value investing. He does extensive homework for his clients and invests for the long term. He looks at a company’s management team, financial structure, and business model, and if all seems healthy, he advises his clients to invest. Though smart and tough, he was also an old curmudgeon. I’d met him a couple of times while I was president of Xerox, but here I was as the brand-new CEO pitching the acquisition of ACS. He was a bit taken aback at first, but he quickly got into it: “Explain this to me. Give me the numbers. Prove to me this is a good idea.” In other words, “Sell it to me.”

Selling a deal can be a show—it’s not just about the numbers but also about you and your confidence in the deal.

Larry was with me and gave his pitch about the financial potential of the combined businesses, and I gave mine regarding the potential for additional services that could be created by increasing ACS’s global reach and raising the ACS offering by applying Xerox’s world-renowned research and development, strong brand, and excellent reputation.

Selling a deal can be a show—it’s not just about the numbers but also about you and your confidence in the deal. But in the case of Neuberger Berman, they couldn’t have cared less about how passionate or impressive I was. They’d been through presentations like ours a thousand times. The long-term investors just wanted to see the numbers and ask fifty questions—“Have you thought about this?” “Have you thought about that?”

I don’t know whether we got their vote or that of another major investor who already owned stock in both Xerox and ACS. What I do know is that in February 2010, 96 percent of Xerox shareholders voted in favor of the acquisition, along with 86 percent of ACS shareholders. With that, ACS became Xerox Business Services, our total market opportunity rose to $500 billion, and our employee base grew to 130,000.

* * *

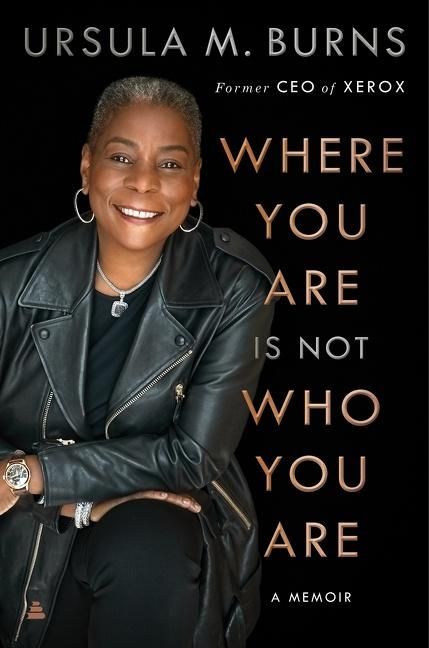

From the book Where You Are Is Not Who You Are: A Memoir by Ursula Burns. Copyright 2021 by Ursula Burns. Reprinted by permission of Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.