The highest-performing teams don’t work inhuman hours. They don’t have bottomless budgets. They’re not always built with the brightest people, either. No, the problem that slows most teams’ progress is that we exchange information in terribly inefficient ways.

Instead, the best teams operate at a higher velocity because they require less time to execute a decision that moves their area of the business forward, and in the right direction.

Much is now being written about the value of asynchronous communication, and I’m a big fan of it. But we’ll always have meetings where we speak to other humans in real time. Throughout these meetings, we all suffer through — and speak — sentences that are longer and less thoughtful than they could be. This slows the amount of ground we can cover, requires more time to get on the same page, and introduces all kinds of tangents and dead ends.

For example, you pose a question…but then share a story from last week that led you to ask the question, provide a few possible options for how your counterpart may opt to answer, add what you’ve already considered, and finish with, “So, yeah. Any thoughts?”

Meanwhile, your counterpart understood what you were asking in the first 10 seconds, is waiting for their turn to talk, and has an entirely different (and more helpful) way to approach the question.

So what do we do about it?

The Formula for Building a Minimum Viable Sentence

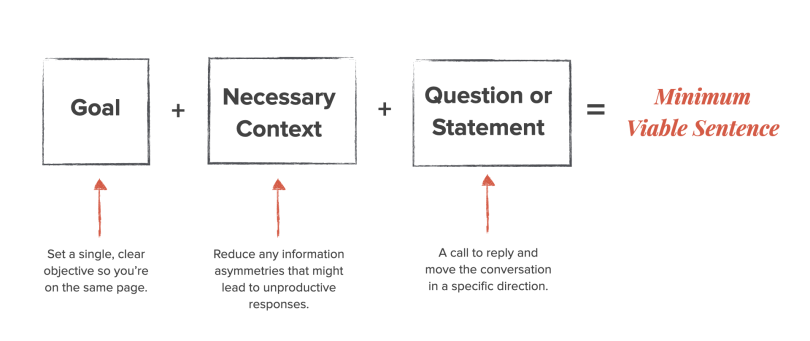

Enter the MVS: the Minimum Viable Sentence. You’re likely familiar with the MVP, as in Minimum Viable Product. An MVS uses the fewest words you need to move a conversation forward. Just enough information to engage with productively.

It can be a question, or a statement replying to a question. It’s also built one step at a time, and increases in complexity as the conversation with your counterpart continues. Here’s how it works:

A Minimum Viable Sentence Uses the Fewest Words Necessary to Move a Conversation Forward. It Has 3 Parts:

- Goal: Set a single, clear objective so you’re on the same page.

- Necessary Context: Reduce any information asymmetries that might lead to unproductive responses.

- Question or Statement: A call to reply and move the conversation in a specific direction.

Let’s use an example. Let’s say you’re a startup founder trying to increase the number of new users you acquire. However, you’re also trying to keep your costs in check. So you might create the following MVS to kick off a meeting with your marketing director:

How might we decrease our CAC from $3K to $2K next month?

This sentence is just 12 words.

In it, you’ve included a goal (a $2K CAC, or cost to acquire a customer, which combines users acquired and cost spent), the context (your CAC is $3K, showing you’ve looked at the data, and are removing any confusion about the size of the goal), and you’ve posed a question. Then, you stop to listen.

The MVS wasn’t:

As our marketing director, I know you’re always evaluating spend and return, and I also know that you really depend on the sales team to ensure that the leads you develop turn into customers, so we all share that goal, acquiring customers. But our investors are pushing us to make sure we’re controlling our costs. They think we should get down to a $1K CAC, even though we’re at $3K now. So we talked for a while, and decided that $2K is the right goal. They wanted to see $1K, but I pushed back for $2K. So I’d love to talk through some thoughts, for example, what if we were to offer credits for referrals to our customers that’s less than the amount we’re spending on social ads? What do you think are some other ways that we could get our CAC down?

That rambling paragraph was 143 words, and uses a sentence construction far more commonplace in workplace conversations.

An MVS uses the fewest words you need to move a conversation forward. Just enough information to engage with productively.

Now, to the response. If you were the Marketing Director replying with a MVS, you might say:

Part of that $3K is the cost for tests to determine our best acquisition channel long-term, so is reducing CAC the best focus for us next month?

That’s 27 words, including a goal, context, and a follow-up question.

Hearing this MVS, the founder may realize, “Oh, I can tell our investors that in the short-term, their money is being well-spent because we’re learning the right acquisition channels before we scale our performance marketing,” and take the conversation in a new direction.

However, if the founder led with Option B, not the MVS, the marketing director may have been lost in the clutter, landing on an entirely different train of thought. “Should I list out all the ways we can decrease CAC to show that I’m knowledgeable? Are the investors doubting that I can help us scale? What if I don’t meet my budget KPI because of this?”

5 Principles for Creating an MVS

This may seem foreign at first, but know that you’ll learn to build a MVS easily, and on-the-fly, without formulas and principles. These aren’t things I actively think about in a conversation anymore. They’ve become part of an ad-hoc mental model I draw on throughout my day.

5 Principles for Creating a Minimum Viable Sentence

- Have a point of view before the conversation starts.

- Further develop your MVS throughout the conversation.

- Focus on your counterpart’s point of view.

- Use data points, not examples or case studies (when possible).

- Focus on your one strongest point, not all of them.

1. Have a Point of View Before the Conversation Starts

Forming an MVS requires a large dose of thoughtfulness. When we’re uncertain of what we’re trying to communicate, we tend to compensate with longer sentences that allow us to “think out loud,” and work out our point of view as we go.

The French philosopher, Blaise Pascal, famously wrote, “I would have written a shorter letter, but I did not have the time,” because distilling your sentences down into their essences is hard (Lettres Provinciales, Letter XIV). Before you start a conversation, pause. What’s the one point you need to impress, or question you need to have answered?

2. Further Develop your MVS Throughout the Conversation

Much like how an MVP in the product world is built — the minimum feature set needed to deliver value, which is improved by iterating with customer feedback — you’ll pause, listen, and then further develop your sentence after hearing feedback. In our example above, had the founder led with the cluttered, rambling paragraph, the marketing director might have asked why the investors were pushing for a $1K goal, and why the founder settled on $2K. Using the MVS instead allowed the marketing director to ask, “Part of that $3K is the cost for tests to determine our best acquisition channel long-term, so is reducing CAC the best focus for us next month?” This moved them in a new, more productive direction — aligning on marketing priorities, not brainstorming CAC-reducing tactics.

3. Focus on Your Counterpart’s Point of View

The MVS isn’t for selfish, impatient people. In fact, it requires a great deal of selflessness. To use the MVS successfully, you’ll need to identify what’s most valuable for your counterpart to hear, consider what their current context, incentives, and frustrations are, and stop talking to allow them to begin sharing what’s on their mind sooner.

4. Use Data Points, Not Examples or Case Studies (When Possible)

Often, if we’re uncertain of whether we’re communicating clearly, we’ll provide an unsolicited anecdote or tell a story to illustrate our point. However, inherent to a story is more detail than what’s needed to further your conversation. A plotline that’s too broad opens up the possibility of new tangents your listener may follow instead.

The alternative is data. Using a specific data point forces you to research the topic at hand, and a single metric can be worth 100 words. For example, let’s say you manage a team of Account Executives (AE). You’re meeting with a colleague who manages the Business Development Representatives (BDR) supporting your AEs. Rather than sharing how stressed your team feels after falling behind on their quota, and the story of a BDR who’s ramping slowly to explain why, you could do your research and ask, “How can we get BDR-qualified pipeline back to $50K per rep, from the $32K it’s at today?”

5. Focus on Your One Strongest Point, Not All of Them

Neil Rackham, a professor and consultant, studied expert negotiators to figure out why they’re so persuasive. He noticed that most people try to influence others through sheer force, by stacking up a volume of arguments to tip the scales in their favor. But experts do the opposite. They present fewer points, because as Rackham says in The Effective Negotiator, “A weak argument generally dilutes a strong one.” Lead with your most compelling content, leave the rest out.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that we create Twitter IRL, or that this concept be applied to team happy hours and dinner with your mother-in-law. Most moments in our life call for storytelling, free-wheeling, and off-the-cuff comments. This strategy is just for critical business communications, in which speed and accuracy are of the essence. Try out the MVS in a few workplace settings and you’ll quickly see where the concept is most helpful to you.

Finally, this isn’t just a thing for type A people. This is for everyone — whether you’re a founder pitching, a sales rep selling, an engineer collaborating, a customer success agent helping, and so on. We’re all in meetings with other humans, and we all need to work together to move our companies forward with greater velocity.

(And yes, I fully appreciate the irony of using 1,500 words to explain the concept of an MVS.)