News outlets are increasingly covering issues of algorithmic discrimination, predictive analytics and automation, and exploring how they infiltrate welfare communities, policing, healthcare and surveillance of public spaces.

Public officers face some soul-searching today as they straddle AI-enabled efficiency and social justice. Aid agencies and state actors stand on a graveyard of failures of global innovations that claimed good intent — for instance, the last 50 years of trickle-down economics that justified tax cuts for the rich purportedly to benefit the poor.

Few, particularly in Latin America, can forget the crusader Jeffrey Sachs with his “disaster capitalism” in the 1970s. He justified administering “shock therapy” to the world’s economies outside the West as a means for unparalleled economic prosperity for all.

Today, tech saviors offer their AI-enabled medicine packaged as goodness for all to swallow. AI is meant to aid in curing economic recessions, geopolitical wars and planetary degradation.

AI Bias Statistic

When testing the data produced by two separate AI databases, the USC Information Sciences Institute found that up to 38.6 percent of the data was biased, both positively and negatively.

The Oppressive History of ‘Doing Good’

Doing good comes with a toxic legacy of oppression in the name of uplift. The centuries-long colonial project was the most ambitious in its agenda for “doing good.” The English language was one of the most potent instruments to shape the “good subjects.”

During the British Raj, Lord Macaulay, the secretary of war in colonial India, became infamous for “Macaulay’s Minute,” written in 1835, in which he focused on the deficiencies of the Natives’ cultures and languages and proposed the English language as a solution. He argued that it was an “indisputable fact” that Asian sciences and languages were insufficient for advancing knowledge. Only English could truly give us the “enlightenment of our minds” and unravel the “richest treasures of modern thought and knowledge.”

“Macaulay’s Minute” was an “English for Good” moment of the day. English continues to enjoy a privileged place in the former British colonies and is equated with progress, mobility and modernity.

Historically, what qualified as good was often bad, as it translated to subservience, oppression and taming “subjects” to the existing social order. Even today “Uncle Tom” is a slur among African American communities as it has come to mean a “good slave” who complies with his master at his own expense.

A “good woman” of virtue and honor remains a live template in patriarchal societies, though many continue to resist. A case in point is the Iranian women’s uprising, defying the morality police as they burn their hijabs.

A “good subject” for governance under colonial rule was racialized and legitimized by philosophers who are still revered and often uncritically taught in our institutions. Philosopher Immanuel Kant’s hierarchy of “good subjects” was based on supposedly innate traits of entire groups.

For instance, he asserted that Indigenous Americans, as a race, were “incapable of any culture” as they were too weak for hard labor and industrious work. Old intellectual habits die hard.

Automate the Good and Track the Bad

Moral awakenings do happen, however. They have served as land mines in ideologies of goodness, blowing up atomized and culturally myopic constructs.

Today’s intelligentsia has come quite a distance from celebrating the nineteenth century poet-novelist Rudyard Kipling to condemning him. His work fostered empathy for the white man for the “burden” he must carry to transform colonial Natives from “half devil and half child” to “good subjects” worthy of compassion.

Today, tech companies hungry to capture the next billion users markets frame their presence in the Global South in altruistic terms. AI for Good projects driven by tech philanthropy spread the narrative that tech can solve problems of “the natives” by tapping into their aspirational yearnings for freedom, stability and inclusion.

History does not die; it is reborn.

Sometimes in the best of ways, through human reckoning or resuscitation of beautiful ideas of the past. Sometimes in the worst of ways, through a nostalgia for the “good old days” and even a fervent zeal to reestablish moral clarity with a binary logic of good and bad.

To ensure that computational cultures automate the good and track the bad, we need to heed the diversity of contexts and peoples they strive to impact.

The Demand for Data Presence

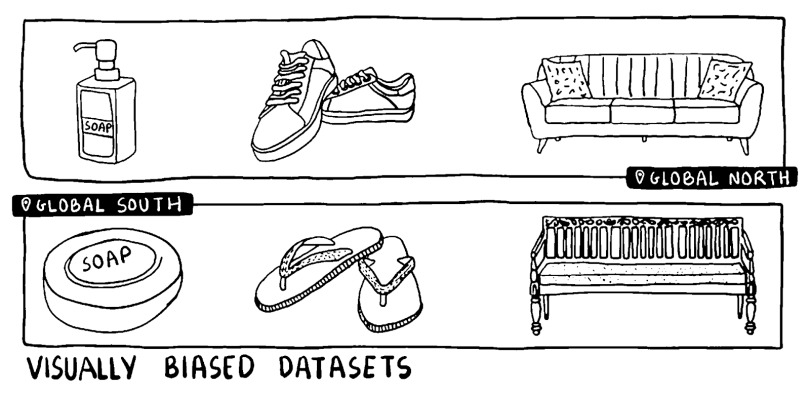

Object recognition algorithms perform significantly worse at identifying household items from low-income countries compared to items from high-income countries.

Researchers at Meta’s AI Lab tested some common household items like soap, shoes and sofas with image recognition algorithms by Microsoft Azure, Clarifai, Google Cloud Vision, Amazon Rekognition and IBM Watson. They found the algorithms were 15–20 percent better at identifying household objects from the United States compared to items from low-income households in Burkina Faso and Somalia.

In less wealthy regions, a bar of soap is a typical image for “soap,” while a container of liquid is the default image used in wealthier counter- parts. Data feeds for “global data sets” for basic commodities come primarily from Europe and North America. Africa, India, China and Southeast Asia are the most under-sampled for visual training data.

The fact is that some groups enjoy more empathy than others due to long-standing efforts to make them visible and understandable. The prototype user for the designs of our everyday lives has long been “WEIRD” — Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic. The rest of the world has had to contend with centuries of colonial and patriarchal baggage, which have resulted in cultural erasures and historical fictions in mainstream narratives.

In The Next Billion Users, I explored how the “rest of the world,” predominantly young, low-income and living outside the West, fall into caricatured tropes. Biased framings lead to biased data sets.

Aid agencies have typically defined the next billion users as the “virtuous poor” — users who are utility-driven and leapfrog their way out of constrained contexts through innovative technology.

Businesses have framed the global poor in recent years as natural “entrepreneurs from below,” ready to hack their way out of poverty and innovate in scarcity. Education policymakers view them as “self-organized learners” who can teach themselves with EdTech tools and liberate themselves from the schooling institution.

These framings generate skewed data sets, which in turn legitimize these framings. The next billion users are very much like you and I — they seek self-actualization and social well-being through pleasure, play, romance, sociality and intimacy. These youth need the state and the market to step up and keep their end of the deal, to provide a security net and fair opportunities.

Disregarding our common humanity contributes to a failure-by-design approach and a graveyard of apps.

Adapted from From Pessimism to Promise: Lessons from the Global South on Designing Inclusive Tech by Payal Arora. Copyright 2024. Reprinted with permission from The MIT Press.