Kyle Stratis loves to learn, but like most people, he doesn’t remember everything he reads. So he has to take lots of notes.

In grad school, Stratis filled notebooks with handwritten summaries of articles. The method was good for recall, but way too tedious. When he became a software engineer, he’d jot things down in a text editor — handy for a quick brain dump, but lousy for seeing connections between different ideas. He experimented with popular note-taking apps, too, but they all felt clunky and rigid.

He fell into a creative rut for about a year. And he started looking for something that would help him dig his way out.

Then, this past spring, Stratis stumbled upon something on Twitter.

He found #RoamCult. The hashtag connects people who use a new app called Roam Research, a “note-taking tool for networked thought.”

Scroll around #RoamCult and you’ll notice a congregation of academics, engineers and artists sharing Roam tips with one another. You’ll see them praise the app, calling it a “game changer,” a “digital mind palace,” a “second brain.”

If you’re a new user, they’ll greet you warmly — they may even invite you to the community Slack workspace.

This much enthusiasm about a software product was enough to intrigue Stratis, so he signed up. When he started playing around with Roam, he understood the hype.

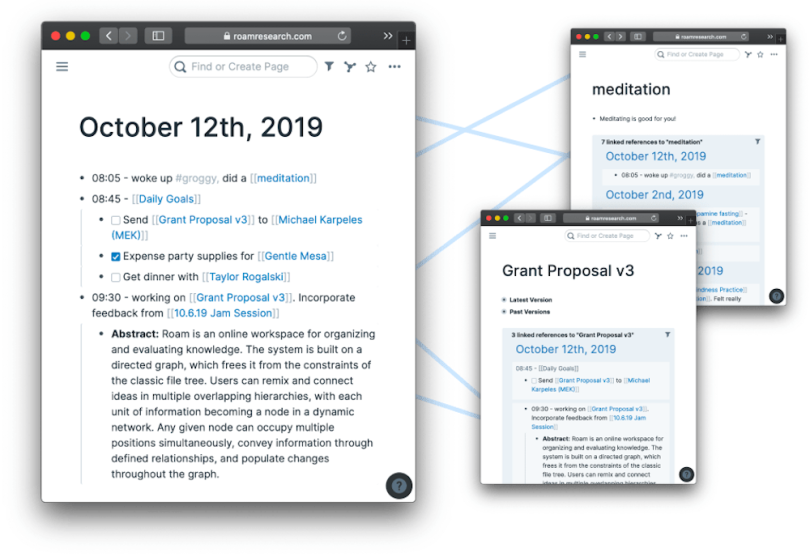

Stratis was awed by the app’s use of bi-directional linking, a feature that lets you make individual notes point to each other. The resulting system looks less like a filing cabinet with folders and pages, and more like a human brain with webs of associations. It helps users map the relationships between ideas.

“I started using it, and everything just clicked,” Stratis said.

It clicked for others too: Roam generated enough buzz since launching late last year that seed investors recently gave it $9 million at a $200 million valuation — about 25 times the median valuation of companies at this stage in their lifecycle, The Information reported.

Roam is making waves. But who, exactly, is it for?

Stratis, an active participant on the Roam Slack, said that, while Roam is probably most useful for people doing “knowledge work” — he’s crossed paths with plenty of scholars, project managers and marketers in the community — the app’s usefulness isn’t confined to a certain job function, per se. Rather, Roam is right-sized for people with a certain outlook — people who, in Stratis’ words, “want to learn more effectively, to understand and synthesize new ideas.”

It seems as though Roam attracts people who see it as more than a note-taking app or a relational database. People who are not just angling for productivity, but who are in a sense hoping to optimize themselves. People who, in essence, want a second brain.

The Road to Roam

Roam is the newest shining star in an increasingly crowded galaxy of apps designed for organizing your life.

In April, a startup called Notion, whose app serves similar purposes, raised $50 million at a $2 billion valuation. Evernote, an elder in this space that once stirred Roam-like zeal, recently declared its intention to reboot. There’s also Apple’s Notes, Bear, Todoist, OneNote, Obsidian, Ulysses, TiddlyWiki, Workflowy and many others that, all in their own ways, try to help people stay more organized and efficient.

“The human mind does not work that way. It operates by association.”

Many of these digital tools have sprouted just within the past few years. But the concept behind them dates back much further.

You can trace bi-directional linking in note-taking back to 1945, when The Atlantic published renowned engineer Vannevar Bush’s essay “As We May Think.” Bush lamented how difficult it was to learn when resources were organized by hierarchical classification systems, like alphabetical or numerical order. “The human mind does not work that way,” Bush wrote. “It operates by association.”

Bush dreamed up the future he wanted. He sketched out a vision of a hypothetical device called a memex, a personal mechanized library that would rely on “associative indexing,” rather than hierarchical filing systems. The memex, he wrote, would be able to replicate how humans really think and learn. It would provide “an enlarged intimate supplement” to our memories.

The dream was partially kept alive by Ted Nelson, the man who coined the term hypertext, as he spent decades trying to create a network with a fully bi-directional infrastructure in a project called Xanadu.

Alas, the web as we know it still doesn’t work that way, and Wikipedia is probably the closest mainstream approximation to Bush’s dream that we have.

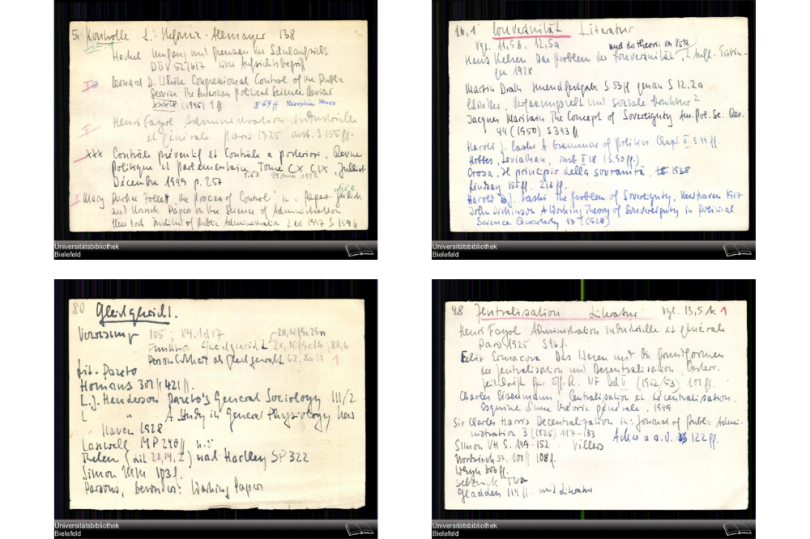

Another touchstone is Zettelkasten, a note-taking method popularized by Niklas Luhmann, a German sociologist. He credited Zettelkasten with helping him write dozens of books over the course of his career. The system calls for taking quick notes on paper index cards, giving each a number, tags and cross-references to other notes before sorting them into little boxes. That way you can quickly retrieve information and make connections between ideas that you might not notice if you took notes using traditional approaches.

The Zettelkasten and other personal knowledge organization methods produced dedicated followers, but remained largely on the fringes.

Until our digital capabilities caught up. Eventually, the proliferation of software apps — and, perhaps, the influence of self-optimization tacticians like Tim Ferriss — allowed advanced note-taking methods to reach new audiences.

Now, Zettelkasten and other knowledge-management techniques are remixed into courses and seminars and marketed to digital-native knowledge workers hoping to unlock their full productivity potentials. One of the more popular ones is literally called Building a Second Brain.

You can spend hours tumbling down a YouTube rabbit hole of people giving tutorials and showing off their personal workflows on tools like Roam, Notion, and the rest.

‘I Check My Roam First, Even Before Google’

How people use these tools varies. But a common approach, I’ve learned, is to use them “for everything.”

Stratis said that Roam has become “the focal point of every workflow that I have,” whether it’s his work tasks, personal to-do lists or brainstorms for potential blog posts. When he has to look something up, he checks his Roam before Googling it. “Because then I find what’s important to me,” he said.

“[Roam] is the focal point of every workflow that I have.”

Stratis explained to me how it all works. The first step is just pulling up Roam and jotting down a note. It could be anything — whatever he’s reading or thinking about. He can then add in bi-directional links.

Say he read a book about urban planning in the Midwest. Stratis could quickly dash out a note that says, “Read a [[book]] about [[urban planning]] in the [[midwest]],” and the note would be forever referenced by any other note that double-brackets “book,” “urban planning” and “Midwest.”

That way, newly created notes connect to already existing notes. It’s a lot like how knowledge works when you learn new information.

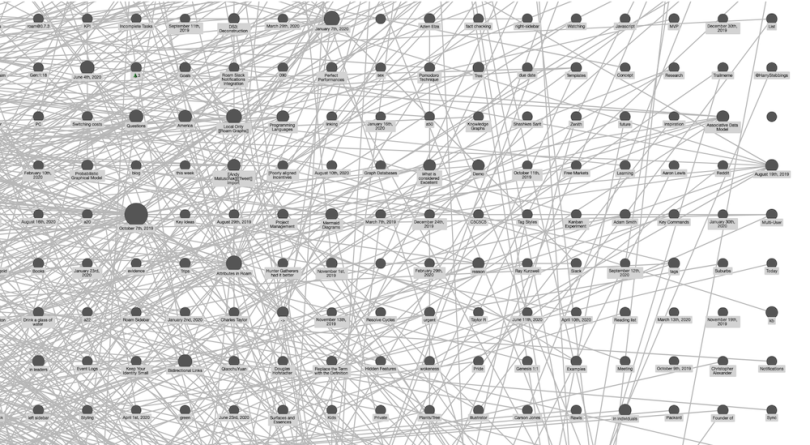

In Roam, you can also toggle over to a graph overview. Doing so creates a visualization of a gigantic web of all your interlinked notes. It looks like an inkblot of synapses. This way, you can see a spray of networked connections, gaining a different perspective than what a traditional view of folders within folders would provide.

When asked if Roam was just a fancier way to store notes, to preserve what knowledge he already has, Stratis said that it does that — plus a lot more. What makes Roam so valuable, he said, is how the act of using it spurs new ideas.

“It really becomes a place for fomenting creativity,” he said. “It’s not just knowledge you end up synthesizing. It’s inspiration as well.”

The idea is that the ability to see links between seemingly unrelated ideas helps spark new ones. So, the “Midwest” tag from the previous urban planning book example could, let’s say, be viewed in relation to a New York Times article you read about the decline of industrial manufacturing in the Midwest. Maybe seeing a literal connection between those two notes prompts an idea for a blog post. You could have missed this link if you simply took notes and filed them away in separate digital drawers the old-fashioned way.

Tools for the New ‘Creator Economy’

But why now? The rise of Roam and other personal knowledge management tools can be partly attributed to the rising sophistication and ease of use of the programs, as well as that of the users themselves. People are much more comfortable navigating computers than they were two decades ago.

With tools like Roam, “you don’t necessarily have to be a programmer to become an advanced computer user,” Nathan Baschez told Built In. Baschez writes the newsletter Divinations and formerly worked in product roles at Substack and Gimlet Media.

He said there may also be some correlation between the rise of bootstrapped newsletters and podcasts and the popularity of tools like Roam.

“These are tools that are really helpful when you’re researching for content you’re creating,” Baschez said. “It’s also useful if you’re building a company.”

He shared that he’s been using Roam in recent months, which coincides with him and his business partner getting their newsletter media company off the ground.

“It’s not just knowledge you end up synthesizing. It’s inspiration.”

Stratis, too, made the connection between the rise of Roam and the surge in individual content creators.

“I think a lot of people are shifting toward working toward their passions. A lot of that is some form of knowledge work. And if you want to excel in that, you have to find the tools that work for that,” he said. “Any sort of craftsperson needs their tool.”

The tool of the modern solopreneur, or an operator in the so-called passion economy, is a do-it-all knowledge management system that’s easy to use and that can accelerate one’s creativity. In short — it’s a tool like Roam.

But What Is This All About, Really?

Is the rise of Roam just the culmination of a decades-long search for a better way to take notes and remember research? Maybe. Or perhaps it’s something deeper than that, something more existential.

Maybe it’s about transcending natural human limitations. The desire to be a god. The fear of death.

“I don’t know if I’d connect it that far,” Baschez said. “I think it’s fear of forgetting. You know when you read a book, and a couple months later you’re trying to remember it, and you’re like: ‘Oh my god, did I learn anything from that? Am I just wasting my time, muddling through the world, like I don’t have a grip on anything, like everything is just slipping through my fingers and I'm not making any progress on anything?’ I think it’s that feeling that powers a lot of it.”

He paused, and torqued his answer into a positive register.

“A lot of people find it fun and satisfying to take ideas seriously and study them and take notes on them,” he said. “There’s definitely some ambition in there, but there’s also a playfulness that’s kind of disconnected from a means to an end.”