“Imagine designing an e-commerce website. You could make the add-to-cart button literally half the page. You have that freedom.”

Cynthia Savard Saucier, UX director at Shopify and co-author of Tragic Design, offered this hypothetical pattern when speaking with Built In not as a recommendation (obviously), but as an example of just how rife product and UX design is with opportunities to spectacularly fail users. But by the letter of more than one ethical design framework, a comically outsized add-to-cart button is not just bad design — it’s also unethical.

What Is Ethical Design?

Because there is no one true-north code of ethics for digital design, parsing what exactly constitutes ethical design can be tricky. Some of the codes that do exist are “well-intentioned” but “clunky” documents that few actually incorporate into their work, said Lennart Nacke, a professor of user experience and gamification at the University of Waterloo who’s researched UX ethics.

The continuum of unethical design could range from algorithmic bias to subtly manipulative confirmshaming. It logically encompasses connected devices with known vulnerabilities and healthcare user interfaces whose density of information has fatal consequences, as outlined in Tragic Design.

Despite the lack of a universal, single source of truth for digital design ethics, plenty of commonalities exist across the many proposed frameworks. It’s clear that ethical design should: resist dark patterns, respect data privacy, prioritize accessibility, be human-centered and encourage co-design.

Ethical Design Resists Dark Patterns

By any framework, dark patterns are textbook antitheses of ethical design. Unfortunately, they appear to be on the rise.

Designer Harry Brignull coined the term dark patterns in 2010 to describe UX tactics that manipulate users into changing their intended behavior, defining them as “tricks used in websites and apps that make you do things that you didn’t mean to.” Types of dark patterns include the “sneak into basket” tactic, where a site clandestinely adds an item to users’ carts, “often through the use of an opt-out radio button or checkbox on a prior page,” and the “roach motel,” in which a service that was easy to opt into becomes arduous to opt out of. Think 12-step subscription cancellation processes or ones that require a long phone call when signing up took just a click or two.

“Increasingly, these strategies are being used as a design playbook. They’ve probably become more ubiquitous over the last decade since Harry [Brignull] first introduced the concept,” said Colin Gray, director of the UX Pedagogy and Practice Lab at Purdue University.

Gray pointed to a 2019 study by researchers at Princeton University and the University of Chicago that showed the common use of dark patterns. The study, which reviewed about 53,000 product pages, found that some 10 percent employed at least one dark pattern in some fashion.

The Federal Trade Commission has taken notice too. The agency sought public comment earlier this year about dark patterns and hosted a virtual workshop to further examine the problem.

Kat Zhou, a product designer at Spotify and the creator of the Design Ethically project, told the FTC that dark patterns persist because designers are heavily incentivized to build experiences that meet growth-focused OKRs, allowing a slippery slope for shady tactics to assimilate into standard UX practice.

“We learn these tactics in universities. We learn these tactics on the job. And that normalization makes speaking up about these anti-pattern designs and these tactics very, very tricky,” Zhou said during the FTC workshop.

Moreover, Gray and his co-authors have studied a trend that extends dark patterns’ generally inconspicuous or sneaky methods into something more “blatantly coercive” — what they call “asshole design,” derived from a popular subreddit of the same name.

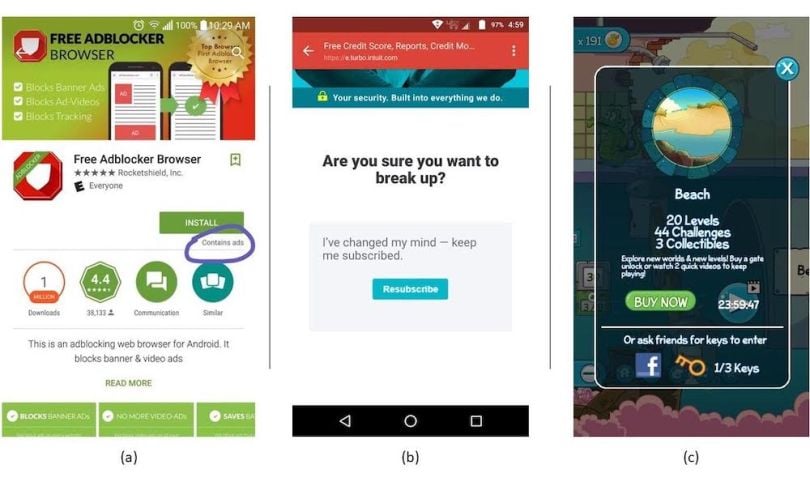

The above image shows some of these tactics in action. The left is an example of a confusing design that uses contradictory information: an adblocker that contains ads. The center example, meanwhile, shows an unsubscribe page where the only button is to resubscribe — an example of a pattern that blocks users’ intended pathways. And the right — an in-game pop-up that requires the user to either make a payment or watch ads — is emblematic of what Gray and his co-authors dub “entrapping” designs.

Mike Monteiro, co-founder of Mule Design Studio and author of Ruined by Design, told Built In that designers are hired not only for their ability but also their expertise, which includes the knowledge that such patterns are unethical. That creates an obligation to advocate against their use, he said. That also begs an obvious question (how?) and we’ll explore advocacy resources below.

But first let’s consider other important aspects of ethical design.

Ethical Design Is Accessible

Despite the potential for lawsuits, accessibility tends to be deprioritized in web and application design. It sounds good to pretty much everybody in the abstract, but not necessarily in the time and effort it requires.

“Everyone’s okay with the concept of accessibility. They understand intrinsically we should be including everyone,” said Michele Williams, a UX accessibility educator and consultant. “Not everyone is on board with the work that comes with accessibility.”

Oftentimes, companies turn to after-the-fact would-be solutions like widgets and overlays. But these frequently fail to provide the hoped-for legal cover, since they tend to generate inaccurate information — such as incorrect alt text for images — and don’t address the underlying code. At worst, they actually worsen accessibility in the process.

Companies that are serious about not only hitting baseline ADA legal requirements but centering accessibility in products are urged to bake accessibility into their design process and consider it from the very start. But what does that mean in practice? It means both revamping early stage design processes and promoting education, according to Williams.

UX and product teams should check their decisions against established guidelines for information architecture, color and contrast, and other UX, interface and content details. That said, the nuance of each consideration varies by project, so designers have a responsibility to self-educate and advocate for larger training throughout the organization, Williams said.

Following the fundamentals of the Web Accessibility Initiative and the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, published by the World Wide Web Consortium, is a basic first step, while resources like the A11y Project and the Stark library can further the foundation, she said.

“It doesn’t make sense to hyper-focus on a project and not get that foundational understanding,” Williams said.

For accessible user research, consider services like Fable, a group of testers with disabilities, who together use more than 20 assistive technology configurations.

It’s true that accessibility research can be more time- and cost-intensive, but the explanation for why companies often fail accessibility is even simpler than time and budget. It comes down to internalized ableism, which leads to erasure, Williams said. “We don’t value disabled lives.”

Any design that aspires to be ethical cannot do the same.

Ethical Design Embraces Co-Design and Is Human-Centric

The push for ethical design is also emblematic in two recent evolutions in design terminology: the move from “participatory design” to “co-design” and from “user-centered design” to “human-centered design.”

These aren’t simply semantic differences — or they shouldn’t be, at least. Simply put, participatory design is designing for people, perhaps allowing them some manner of involvement but no significant decision-making power. Co-design means designing with people.

Liz Jackson is the founder of The Disabled List, which pairs disabled designers with leading design studios. At a 2019 talk, she spoke about how embedded design concepts like user empathy can border on extraction. User empathy can “feel a little bit less like empathy and a little bit more like designers are coming in, gleaning our ideas and our life hacks, and then selling them back to us as things that are inspirationally done for us without ever giving us credit.”

In the talk, Jackson recalled being told about a new technology intended to help disabled people get hired. “What disabled people did you hire to create this technology that’s intended to get disabled people hired?” she asked. “They said, ‘none.’”

In ethical design, products intended to serve a specific population must meaningfully include that population throughout its design.

Similarly, the shift from user-centric to human-centric design ideally represents a transition beyond just language. For NowNext founder and Future Ethics author Cennydd Bowles it means considering your product’s consequences for all, not just its immediate user base.

“Even if someone isn’t a user of our products, if they are affected by our products, we still have to try and anticipate their potential harms,” Bowles told Built In last year. “We have a moral obligation, if not eventually a legal one, to try to mitigate them in the same way tobacco firms are held liable for passive smoking.”

A human-centric approach must also place a premium on inclusive and equitable design, as Vivianne Castillo has stressed. Castillo focuses on such work as founder of HmntyCntrd, a community and course provider for UX professionals focused on equitable design.

During a recent appearance on the UI Narrative podcast, she stressed that individual designers need to self-interrogate their biases and influences, and also “be intentional in developing your skill set and awareness around supporting … and helping other people.”

That includes pushing for equitable work environments. “If you aren’t human-centric in the workplace, that’s 100 percent going to impact [employees’] ability to understand what it means to be human-centered in design and the experiences that we’re creating,” Castillo said at a Fast Company summit earlier this year.

How to Advocate for Ethical Design

For a recent paper, Richard Wong, a tech ethics researcher at the University of California Berkeley’s Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity, interviewed UX professionals to study tactics for bringing social values to UX work.

In it, a UX researcher named Laura, who works for an edtech company, is quoted recounting an attempt to include people from Indigenous communities to her user research interview pool. “But when I was talking about [recruiting users from tribal colleges], even our product marketing person who does think we should help people and care about people, was like ‘Yeah, but we can’t make a marketing strategy specifically to them because there’s not a large enough population of them to warrant us to spend that money,’” Laura said.

Her workaround? “We should try to figure out what group do they align with the most,” she said. “Is it rural students? Okay, that then broadens the population, makes the business case a lot more easy to fight for and also we’re not making a claim that we cannot live up to.”

Both the resistance and solution — “imperfect but tactical,” as Wong called it — may ring familiar for UX professionals. Some “perfect is the enemy of good” strategy is often at play.

“Between the path of doing nothing and doing everything, there’s a lot of breadth of potential action points,” said Saucier, of Shopify.

For example, if a designer’s more ethical recommendations aren’t implemented, put in place tripwires and tracking — such as monitoring customer service problems related to the feature in question — “to make sure it does not hurt users,” Saucier said.

Nacke, of the University of Waterloo, recommends the Ethics for Designers toolkit, which includes resources like a moral value map. When prototyping a new feature, designers can use the map to identify values they consider most important and how that design might intersect with and affect those values.

Also consider phrasing ethical concerns in different terms, Gray, of Purdue, said. If a design choice threatens accessibility, frame it in terms of legal cover. If you’re pressed to use a dark pattern, stress the long-term brand management risk.

“Most organizations aren’t going to care about [a design pattern] because it’s ethical,” he said. “So we can think instead of reframing it around ... an accessibility, regulatory or legal liability issue. Other kinds of framings may have better penetration within the organization than just saying this isn’t the right thing to do.”

Of course, any number of power dynamics can make it difficult to press an issue. It can be especially difficult for more junior designers and those who’ve yet to establish relationships with company leadership. Designers who are in a position to advocate more directly shouldn’t underestimate the power of tone. Being forthright can go a long way in preventing tactics like dark patterns, Monteiro, of Mule, said. When a line is crossed, “say, ‘This is unethical. This will hurt people. And if need be, I will not build it.’ A lot of times just hearing that from the people charged with building the thing might be enough to give folks pause,” he said.

In Monteiro’s experience, pushing back against design requests for excessive data collection was the most common ethical conflict he had to initiate. “Until you have an actual, solid reason for asking for information, don’t put it in spec,” he said.

Saucier emphasized the importance of voicing concerns as well. “People actually have a lot more power than they realize,” she said. “They have a lot more space to influence the decision-making process. They can discuss, they can advocate and, if they can’t make a change right now, they can at least educate for later.”