Several years ago, #AirbnbWhileBlack shot to Twitter prominence. Applying the hashtag to their tweets, Black users shared examples of discrimination by hosts on the home-sharing site.

The conversations caught the attention of Airbnb co-founder and CEO Brian Chesky just as a 2017 study by Harvard Business School researchers, slated to appear in the American Economic Journal, found that “guests with distinctively African-American names are 16 percent less likely to be accepted relative to identical guests with distinctively white names.”

“This was an existential risk to our business,” Chesky told hosts Aarron Walters and Eli Woolery on a recent episode of the Design Better podcast. “If the company is committed to, basically, making sure people feel like they belong, the opposite of belonging — or an obstacle to belonging — is discrimination. So if you’re truly committed to this idea, then you’ll fight against obstacles toward it. That just seems completely obvious.”

Chesky’s words position host discrimination as both a human problem and a business problem, and, of course, it is. But, for Airbnb, it was also a design problem requiring a carefully coordinated response. Modern companies, according to Chesky, serve multiple stakeholders — including, increasingly, the public at large — and those that are successful must acknowledge these stakeholders’ interests and invite them into the design process at early stages.

“I think it’s really important that you design the company that you’re in. You don’t just design the products that the company makes.”

Bringing people to the table, making them feel heard and translating their ideas into a brand vision or decisive public action is the hallmark of design maturity — an industry term of art signifying how well an organization is infusing a design framework into its core business practices. The idea is about much more than building a sleek, user-friendly interface or boosting conversion rates.

“I think it’s really important that you design the company that you’re in. You don’t just design the products that the company makes,” Chesky said.

Waging a Coordinated Design Response

Airbnb took some decisive steps to combat discrimination. First, it required hosts to sign a community compact pledging they would not discriminate against guests — essentially an honor code. More than a million active hosts did not sign the pledge, and they were taken off the platform.

Airbnb also limited hosts’ exposure to guest profile photos — signals that could be used as grounds for discrimination. Guests profile pictures are no longer viewable until after a booking is confirmed, and the Instant Booking feature hides names and photos until after bookings are approved.

Still, these decisions felt somewhat arbitrary, Chesky told Walters. So Airbnb hired former attorney general Eric Holder and former American Civil Liberties Union executive Laura Murphy to draft a report scoping the problem and propose market changes to reduce discrimination. They invited key stakeholders, including the civil rights organizations Color of Change, Asian Americans Advancing Justice and the Center for Democracy and Technology to help launch the anti-discrimination initiative known as Project Lighthouse.

The ultimate goal of the task force — still very much a work in progress — is to design a system to measure discrimination based on a user’s perceived race.

For a company founded by two trained designers (Chesky and Joe Gebbia, co-founder and chief product officer, both went to the Rhode Island School of Design), the decision to place collaborative design at the center of its response is not all that surprising.

More interesting, perhaps, is that a similar story is being repeated by enterprise companies across industries, according to Jeff Chow, vice president of product at InVision.

As Fortune 100 companies ramp up efforts to undergo digital transformation, he told me, more and more of them are adopting a similarly broad view of design. Design, for them, is not just the product of an exclusive group puzzling over color variations on a website. It’s a collaborative process to define business priorities and public responsibilities, understand customer needs — even who customers are — and coalesce around brand visions that express a particular point of view.

Often this coincides with digital transformation. According to a second-quarter 2020 report from the market research firm Forrester, “66 percent of global services decision makers say their firms are currently involved in a digital transformation that requires greater cross-functional collaborative work, which means that teams are collaborating more than ever.”

Design Maturity Is a ‘Cultural Shift’

Design maturity can mean a lot of things: that a company is cross-disciplinary and engages stakeholders early in the design process; that design is democratic and ideas can bubble up from anywhere; that design integrates data-driven research methods and shared documentation; that design is embedded at all stages of the product development cycle and involves the perspectives of board members and senior management.

Perhaps most important, Chow said, design maturity is “not about the designer. It’s a sort of cultural shift in the way of thinking. So it starts long before anyone creates their first artboard.”

“[Design maturity is] not about the designer. It’s a sort of cultural shift in the way of thinking. And so it starts long before anyone creates their first artboard.”

During the past decade, he told me, InVision has evolved from a company with a “design-centric point of view” to an organization that defines itself by its intellectual leadership in the design space.

Improving that collaborative process is one of the goals of the company’s latest update, a new gallery of design templates released in November for its online whiteboard Freehand. Chow told me the templates offer a glimpse of the brainstorming and ideation frameworks companies on a path toward design maturity use in their product development processes.

Designing the Collaboration Process Itself

The publicly accessible templates — developed by enterprise organizations, including Atlassian, Amazon, IBM and Xbox, and design experts like Dave Gray, founder of the visual consultancy XPLane and Steph Cruchon, founder of Design Sprint Ltd — include options for brainstorming, customer journey mapping, sprint planning, affinity diagramming and product launches, among others. Users can open and work in them without an InVision account.

Enterprise customers can also create proprietary templates for internal use.

The simplicity of the design, and the raw look of the visual output, is intentional, Chow said — a way to take pressure off non-designers and help alleviate “blank slate syndrome.” That might mean C-suite executives or outside stakeholders who have valuable ideas about, say, the steps in a user flow or the accessibility of a prototype can contribute to early ideation sessions. Thanks to the templates, participants without the formal design skills needed to express their thinking in a vector graphics editor, like Figma or Sketch, can still take part.

“It’s about having anybody, not just power users, feel like they can contribute,” Chow said. “The payoff is, then, once it hits the design front, the development front, you’re solving the right problem with the highest impact for the customer.”

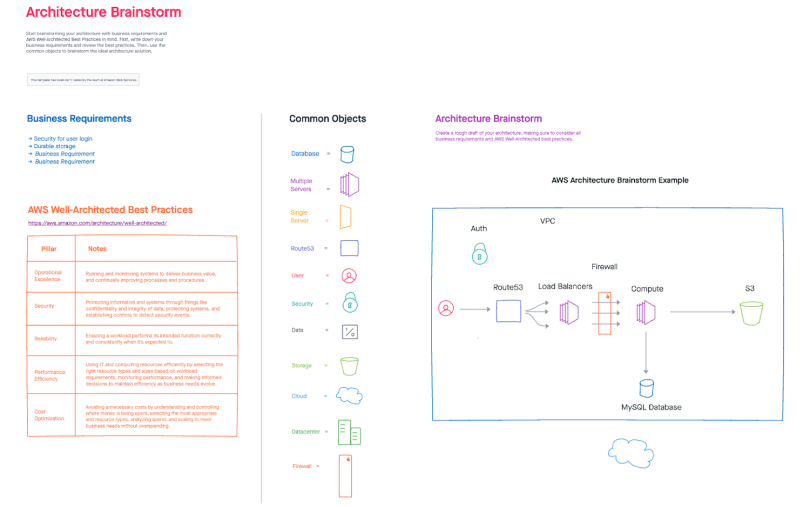

Sharing his screen over Zoom, Chow showed me a few examples. Arranged on a white canvas, the chief organizing elements of an architecture brainstorm developed by Amazon include a description of AWS business requirements, a table of best practices and a list of common objects — users, servers, databases, security elements. These objects are represented as colored icons, and they map AWS’s architecture in a simple diagram.

“It’s about having anybody, not just power users, feel like they can contribute.”

“It’s a diagramming solution for solutions architects,” Chow told me. “But it’s also paired with the business value. AWS is classically a very back-end function. But they are deeply engaged in a design maturity thought process, which means including various stakeholders along the end-to-end journey of solving a problem.”

Atlassian’s contribution is a sprint planning template. The page layout includes an agenda, team member list and placeholder frames for summarizing key points, plotting potential risks and evaluating team capacity.

Familiar reaction emoji like lightbulb, thumbs up and 100 percent icons are intended to encourage team members to weigh in on ideas in progress, Chow said. They’re more interactive than the recent trend for team members to audibly clap during video calls, and they provide a way to upvote — or downvote — early concepts.

“It doesn’t take the place of Jira or Confluence [Atlassian collaboration and workflow tools],” Chow said. “What it does, though, is it says there are messy moments throughout any process of brainstorming where we can get more people involved to figure out how you get to a place to start formalizing the sprint plan.”

What Sets Design-Mature Companies Apart?

With an eye toward advancing companies toward design maturity — in which tooling plays no small part — InVision recently published a 43-page report called “The New Design Frontier.” The study aggregates survey data from 2,200 companies across 24 industries and 77 countries to reveal what differentiates neophyte design organizations from high-performing ones.

A key focus of the report — purported to be “the largest global study of design in business”— is a progressive scale of design maturity that moves from Level 1, where design efforts are focused on “the most visible aspect of design — the pixels on the screen,” to Level 5, where design is fully enmeshed in business strategy, from assessing a product’s market potential to conducting revenue and valuation forecasts.

Put simply, as teams deepen and expand the role of design within their organizations, they move up the ladder — from producers to connectors to architects to scientists to visionaries. Companies that follow a design-maturity model report a positive impact on customer satisfaction and product usability.

In addition, according to the report, the more design is at the heart of a company’s focus, the more likely the company is to observe design’s effect on revenue, valuation and time to market. Level-5 companies are four times more likely than Level-1 companies to report design’s impact on revenue, six times more likely to report its impact on time to market and 26 times more likely to report the impact on valuation.

Though the report does not list the status of companies by name, it offers several instructive findings.

First, healthcare, pharma, IT, advertising, transportation and automotive tend to be more mature, on average, than the whole of the companies surveyed, while education, retail, non-profit and banking sectors lag behind.

Second, most Level-5 companies are fairly small — with design teams averaging just 15 people.

These top-level companies are also rare. Just 5 percent of companies attained a Level 5 ranking. The report notes that, while “skeptical executives may assume this kind of strategic design is only for digital disruptors like Lyft or Airbnb,” Level-5 companies are found in every industry.

What’s the connective thread among them? Collaboration.

Or, as the report’s authors put it: “The top 5 percent of organizations are tackling design in a truly integrated way that is elevating strategy, increasing market share and surging employee impact. Designer-to-developer ratios are at a healthier balance, design systems are commonly adopted, and user research is baked into most workflows.”

Could ‘Belonging’ Become Design’s Watchword?

Much of this, of course, presumes online tooling can help drive real change. Whether InVision’s Freehand templates or those of competitors like MURAL and Miro are needed to promote design maturity — and which software is best for the purpose — remain open questions.

But there’s growing evidence of the need for greater cross-disciplinary collaboration, such as the findings in the 2020 Forrester report. Coupled with surging interest in online design tools — since the spring, demand for Freehand increased by 130 percent — this suggests the pandemic has accelerated the pace at which companies are embracing the power of design at all levels: from users up to leadership.

“People can’t shop in store, and they can’t go out to eat,” Sarah Spagnolo, vice president of communications at InVision, said. “So apps are ever more important, which means there are more and more eyeballs, which means collaboration needs to be more and more a part of a strong development process, because revenue and valuation is so intimately tied to all these things.”

Those who adopt a design maturity framework to guide digital transformation, she said, are the companies that will succeed.

“You can hear the story through all sorts of examples, through the success of Home Depot or the demise of Lord & Taylor,” Spagnolo added. “The ones that are able to collaborate and get the best minds working together earliest have success, whereas the companies that don’t understand or aren’t putting the right people in the right positions to succeed have a harder time in this very challenging moment.”

“The thing that is amazing in the design industry, in general, is this willingness for everyone to want to share their best practices with each other.”

It also appears that the proprietary nature of design platforms is gradually giving way to something more open and accessible — whether that’s due to a rising collectivist ethic, the ongoing battle for eyeballs or the apparent long-tail benefits of freemium models.

“The thing that is amazing in the design industry, in general, is this willingness for everyone to want to share their best practices with each other,” Chow said.

If Airbnb’s quick-pivoting, design-centric business model suggests the way forward for more enterprise-level companies, the idea of belonging may soon be the focal point of design conversations taking place among senior leadership, investors and board members. Who can we bring to the table? What do they have to share? How can we make it easier for them to have a voice?