Much dust still hangs in the air due to a spate of recent, high-profile hacks. The SolarWinds supply chain hack, the Colonial Oil Pipeline ransomware attack, and last week’s Kaseya attack that combined ransomware with a supply chain attack against a managed security supplier have all captured the public’s attention.

The stark reality is that most private companies and governmental organizations have underinvested in cybersecurity. Hackers can easily breach the average organization. Hence, if a company or agency invests the average amount in cybersecurity, chances are it will face a breach at some point, whether it knows about the attack or not.

Systematic Underinvestment

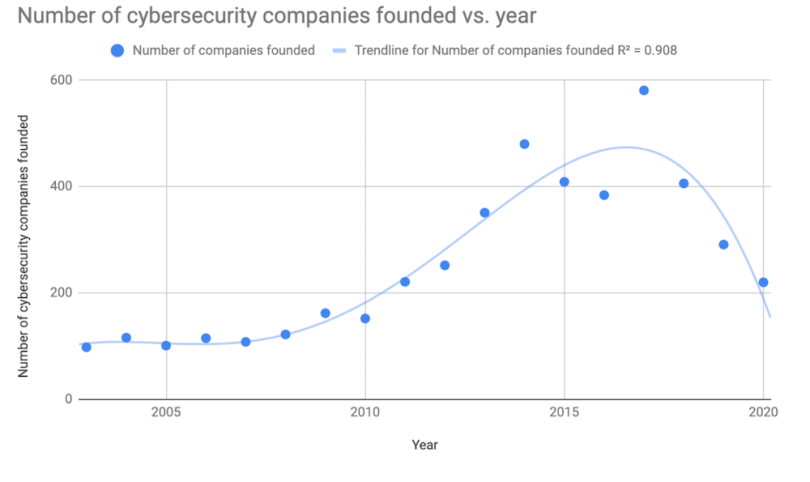

As a community, we have failed to adequately and consistently invest in cybersecurity. To date, venture capital, private equity, and public IPO investments have contributed over $45 billion to cybersecurity initiatives. Such investments picked up in 2014 after the mega-breach at Target, and the number of cybersecurity companies funded continued to increase until 2017.

Starting in 2018, though, the investment fad in cybersecurity seemed to die down. That decrease continued through the end of 2020, in part due to the COVID-related economic recession along with the abatement of the faddish interest in the subject.

Despite the declining investment trends, big breaches have continued, showing that cybersecurity shouldn’t be treated as a fad. The underlying problems aren’t going to magically go away just because some level of investment has been made. Deep problems remain in our digital infrastructure. In fact, they’ve gotten worse, in part due to COVID-19’s impact on the field.

Security in the Pandemic

In March 2020, many organizations were forced to go from approximately 20 percent of remote workforces to over 70 percent. To enable that level of remote work in the face of constrained corporate VPN resources, many organizations did not require all traffic from remote worker laptops and devices to go through the VPN. This measure was designed to cut costs while still supporting a large employee base that suddenly went remote. As such, all traffic was also no longer going through corporate firewalls or network intrusion and detection systems that had been invested in over time.

In addition, since the pandemic began, much of employees’ online activity has happened behind unmanaged and relatively insecure home routers. COVID-19 has taken an already challenging situation in which foreign nation-state attackers and organized cybercriminals already preyed on potential victims and likely made things worse.

In fact, the SolarWinds attackers, after initially breaking into the system in late 2019, stepped up their attack activity in earnest in March 2020 when they started deploying malicious code updates via SolarWinds’ compromised product. The malicious code updates started going out around the same time that employees began working remotely. Though the timing may have been coincidental, malicious code updates were sent to approximately 16,000 SolarWinds customers during the first few months of lockdowns. Nine government agencies and approximately 100 private sector companies have been compromised as a result thus far.

First Steps

This past March, the government held congressional hearings in the wake of the SolarWinds attack to discuss policy approaches to the cybersecurity threat. Unfortunately, most of these ideas are too long-term, too slow or otherwise insufficient. These include threat intelligence sharing, a new law focused on hack and breach reporting, and growing the cybersecurity workforce over time.

Threat intelligence sharing can be helpful when some organization detects a threat in a timely manner. As in the case of the SolarWinds attack, however, if no organization detects the threat until a year later, then there is no intelligence to share until the initial detection takes place. Hence, threat intelligence sharing is not sufficient if detection capability is not good enough.

A new law regarding hack and breach reporting will be helpful, but it may take months or years before such a law is passed at the federal level. Likewise, growing the cybersecurity workforce will take years to train enough people to make a dent in the problem.

Taking the Offensive

Instead of waiting for a government agency, such as the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) to centralize threat intelligence sharing, we need to take advantage in the short term of the many existing platforms and groups who already have these tools. Existing groups such as the Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center (FS-ISAC), and companies, such as Anomali, can work to counter attackers right now. But we shouldn’t wait to centralize threat intelligence sharing before getting more aggressive about detection capability and leveraging existing threat intelligence sharing groups.

FireEye, perhaps in part due to its diligence and sophistication and in part due to luck, detected the SolarWinds hack approximately one year after it had started. As a community, though, we can’t rely on getting lucky, and most organizations are not as sophisticated as FireEye. What existing attacks may have already taken place and still lie undetected?

Joe Biden’s executive order on improving the nation’s cybersecurity from this past May was a step in the right direction. It orders many federal organizations to review and update their requirements and standards and requires service providers to collect data relating to cybersecurity and report incidents of which they become aware. Many organizations are currently using old, out-of-date, legacy systems to operate, monitor, and defend power grids, dams, water treatment facilities and oil pipelines. Biden’s executive order may require these organizations to leverage modern cloud technology and migrate to a zero trust architecture.

More standards and regulations alone without focused action are unlikely to help, as CISOs already have hundreds of checkboxes to comply with. We need to focus on a much smaller set of technical root causes and scientifically effective countermeasures to address those root causes. The six most common technical root causes of breach are phishing, malware, software vulnerabilities, unencrypted data, third-party compromise, and inadvertent employee mistakes (aside from phishing). Strong, scientifically effective countermeasures are available for many of them.

For instance, Google has been using hardware security keys for multi-factor authentication since 2017 and has not experienced one successful phishing attack amongst employees that use the countermeasure even though Google is regularly targeted by malicious nation-states.

6 Common Technical Root Causes of Data Breaches

- Phishing

- Malware

- Software vulnerabilities

- Unencrypted data

- Third-party compromise

- Inadvertent employee mistakes (aside from phishing)

The country is constantly under attack now, and we need to focus on initiatives that can bolster investments in cybersecurity immediately. Approaches that encourage cybersecurity spending, such as a tax credit to corporations and small businesses for cybersecurity investment, along with guidance as to what to spend the money on could help now. Additional policy changes, such as those put together by the Aspen Cybersecurity Group, combined with initiatives that can be executed in the short-term can also help.

Beyond Policy

Governmental policy should frees up money for cybersecurity, but this area should become a major area of investment for private funding as well. Sophisticated venture capitalists already realize that cybersecurity is going to be an evergreen area, and others should follow their lead. The important questions to ask now are how much more investment is necessary, and which directions should those investments go in?

Once funding has been secured, we need to focus cybersecurity investment on cost-efficient countermeasures that can prevent the root causes of breach. Good places to start include hardware security keys that eliminate phishing and account takeover, artificial-intelligence based anti-malware, next-generation software vulnerability scanning and so on. Much discussion at the SolarWinds congressional hearing focused on kicking the intruders out of our networks, but if we don’t focus on preventing root causes of breach, attackers will likely just be able to get in again relatively easily.

In addition to installing cost effective, state-of-the-art defenses against the root causes of breach, organizations also need to leverage the investments that large cloud providers have made in security. Doing so can help make cybersecurity initiatives more affordable for smaller companies, as cloud providers can typically invest more in security due to their economy of scale than can individual companies or on-premises data centers. One of the many useful aspects of Biden’s executive order, in fact, was to encourage organizations to move to the cloud.

As a cybersecurity community, we need to build more trust with each other. Leading companies can set a transparent, collaborative tone. FireEye, for example, was lauded for its forthrightness and transparency after the SolarWinds attack. The faster that organizations transparently report the issues and distribute indicators of compromise (IoCs) or indicators of attack (IoAs), the faster that the community can identify what other organizations have been impacted and take aggressive steps to contain the attack.

We also need to rethink naming conventions in relation to hacks and breaches so as to not vilify victim companies. For example, naming the December attack after SolarWinds is a misnomer. As uncovered over subsequent months, a large fraction of victim organizations did not even use SolarWinds, and the “SolarWinds hack” conducted by a sophisticated foreign intelligence service could have just been named as such an artifact of how we, as a community, discovered the attack over time.

By naming attacks more objectively, response efforts can be more thoughtful and avoid a false sense of security. For instance, executives at an organization might have thought they were unaffected by the “SolarWinds attack” because they did not use SolarWinds software. Nearly one-third of those organizations affected did not use SolarWinds, however, but were affected by another attack vector that the same attacker group had used to break in and compromise systems.

Committing to Security

In summary, although there is still much to clean up from recent hacks and breaches, we need to act in the near term in addition to the longer term. Enterprises and government organizations need to aggressively invest in cybersecurity. They can focus on leveraging cost-effective countermeasures for the root causes of breach to seal the holes that will allow attackers to easily get in again.

In addition, both enterprises and government organizations can leverage the cybersecurity investments made by large cloud providers and centralized technology supply chains. Finally, investors can benefit over the long-term by continuing to invest in cybersecurity companies that provide novel defenses as well as facilitate the adoption and integration of existing defenses for the root causes of breach.