When the curtain opens on the lead singer in Eduardo Miranda’s Shakespeare-inspired opera, “Lampedusa,” she is joined not only by a choir, but by the chirps and sounds of computerized particle collider data — sounds that literally represent the start of a new universe.

“Lampedusa” is a contemporary opera, but it is also an audio representation of particle collider data from the Large Hadron Collider — like a graph, but for your ears. To Miranda, turning raw data into music represents an opportunity to blur the lines between art and technology.

“I want to move the musical language forward.”

“I want to move history forward, I want to move the musical language forward,” he said. “Because if you produce new music, you create a new audience.”

What is the Large Hadron Collider?

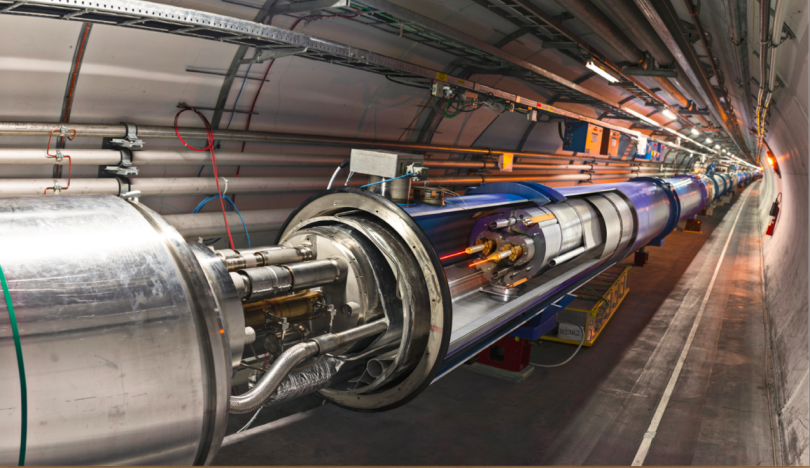

Located in a cavern 100 meters underground in Geneva, Switzerland — at the European Organization for Nuclear Research, also known as CERN — the Large Hadron Collider weighs approximately 7,000 tons and is embedded with hundreds of thousands of sensors.

When this collider is running — it’s currently in shutdown mode until at least spring 2021 — two high-energy particle beams travel at close to the speed of light inside the device and slam together in an attempt to simulate the universe’s conditions right after the Big Bang. Each collision generates thousands of subatomic particles that scatter in all directions. These are some of the tiniest, yet most energetic, particles ever created on Earth.

A particle detector located inside the collider, named ATLAS, analyzes and creates a visual representation of the energy and trajectory of the subatomic particles created in the collision. That data was Miranda’s starting point in composing Lampedusa.

Translating particle collisions into musical notes

Miranda said he has long been fascinated by the idea of creating music from quantum data, since the data itself is literally a representation of the universe’s beginning. He’s not alone in this thought: In 2016, CERN launched Quantizer, a platform that converts ATLAS data into music. But to create “Lampedusa,” Miranda developed his own elaborate system for translating quantum data into songs.

Miranda built software that reformats ATLAS data into a series of numbers that can be fed into MIDI software, which reprograms the data and allows him to encode parameters like notes and timing. Particles with a lot of electron volt energy are registered to a higher note, for example. Particles with less energy translate to lower tones.

“Like a sculptor, you get a raw piece of stone and sculpt it to get a form.”

After turning the individual data points into synthesized sounds, Miranda uploaded the MIDI data into musical notation software called Sibelius, which he used to compose the series of electronic stanzas that comprise the opera. The result is a chaotic, computerized rendering of orchestral musical instruments.

“That’s where the artist comes in,” Miranda said. “Like a sculptor, you get a raw piece of stone and sculpt it to get a form.”

Biocomputers: Making music from mold

Miranda is a computer musician known for blurring the lines between science, technology and art. His best-known experiment was recorded in 2015, when he used slime mold to play a piano.

The experiment was part of his work exploring the potential of biocomputers, which are devices that combine silicon processors with processors made from microbiological organisms. In the experiment, Miranda grew slime mold on an electric circuit board and discovered that it stored information about electric shocks like a memory chip would.

Miranda used wires to connect the slime circuit board to a piano. When he touched a piano key, the slime mold reacted to the note played by altering its biological composition, recording how the electric signal traveled through the circuit board. The slime mold’s reaction was then transmitted to a conventional computer, which released the voltage in the slime’s electric charge. The voltages caused electromagnets hovering above the piano strings to vibrate and play a wobbly piano note, essentially playing back the slime mold’s variation of what the musician was playing.

Miranda said the experiment represented the first biocomputer music ever developed.

Anyway, back to the opera...

A few years ago, Miranda attended a creative conference in California, looking for inspiration from creators in other industries. When he heard he was staying in the same hotel as David Peterson, a language creator famous for writing the mythical Dothraki language spoken in HBO’s “Game of Thrones,” Miranda had the hotel’s concierge leave a note in Peterson’s room explaining that he’d love a chance to talk linguistics over sushi. Intrigued, Peterson said yes.

The dinner spawned a friendship. The friendship spawned “Lampedusa”: a three-act opera intended as a “prequel” to the Shakespearean play “The Tempest.” “Lampedusa” premiered earlier this year at the Contemporary Music Fest at the University of Plymouth, where Miranda serves as head of the Interdisciplinary Centre for Computer Music Research.

It was composed nearly wholly by email, since Miranda lives in the United Kingdom and Peterson lives in Los Angeles.

How to build a new language

Lampedusa represents the second project by Miranda and Peterson. Their first, “Vov,” premiered in 2017 as a three-act short that incorporates synthesized sounds with real singers to talk about the evolution of love. Peterson created the artificial language of Vov — which the work is named after — for the play.

Peterson started by reflecting on what sounds would be meaningful syllables in the new language. He used those building blocks to build words and, from there, a grammatical system. The resulting language includes sounds and grammatical structures that are “very old, very ancient, very different, kind of almost outside the scope of what we understand of modern humanity.”

Peterson created six phases of Vov, each of which builds on the other to reflect historical changes over time. Some language creators use sound change appliers to replicate how time impacts a lexicon, but Peterson prefers to sit down and do the lengthy process by hand. That way, he can build in the spontaneous linguistic additions that defy logic and order.

Vov was an experiment for the two creators. Lampedusa represents their first full work. Because the opera is set on an island that represents the start of a new universe, Peterson decided it would be appropriate to use the most elemental version of Vov to write Lampedusa’s libretto.

Since he didn’t have access to the music when writing the actual lines sung in the play, Peterson said he focused on creating lyrics that could fit into a musical pattern, and kept the line-by-line syllable counts consistent.

“One should expect an opera that takes a famous work and then extrapolates and recontextualizes it.”

“If you’re creating lyrics, it’d be a little weird if a line goes from two syllables to 17 syllables and then to a line of seven syllables,” he said.

Going forward, Miranda said he’d like to expand Lampedusa into a full, two-hour opera, with more than three actors, and perform it at a proper opera house. Peterson said he’d be up for it.

“The funny thing is, the idea he’s doing, I don’t think it’s that out of the ordinary,” Peterson said. “One should expect an opera that takes a famous work and then extrapolates and recontextualizes it. That type of thing is very, very familiar.”