As I write, Kirby is howling from the other room, emitting his distinctive yelp that sounds like a cross between Mariah Carey high notes and a civil defense siren.

A senior rat-terrier mutt with a gimpy leg, my dog hasn’t often been ahead of the pack, but for once, Kirby might be out front. Animal behaviorists are now warning of potential spikes in separation anxiety among dogs.

“An abrupt change in schedule in terms of when or how long a dog is left alone” can bring on anxiety, according to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and countless pets that have become accustomed to 24/7 companionship will soon see their owners return to offices.

Kirby is so ahead of the curve, he whines when I leave the room.

John Honchariw, a dog lover and automation expert, has surely seen this kind of thing — and far worse. His San Francisco-based startup, Companion, has developed an autonomous dog-training device that uses computer vision and infrared cameras. The machine is designed to teach dogs the basic obedience commands that tend to reduce separation anxiety — sit, down, stay, recall. His invention can be particularly useful for shelters: better-behaved dogs are more likely to get — and stay — adopted.

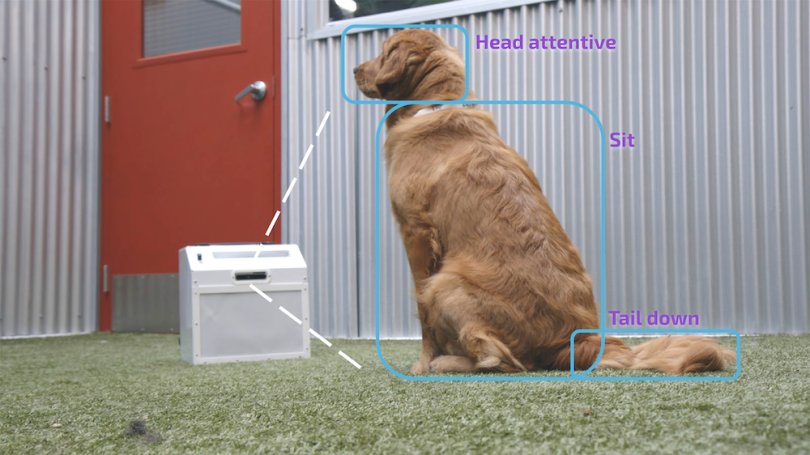

The underlying tech is complex, but the concept is simple: The machine issues the dog a prompt through its speakers (“sit!”), then it shoots out a treat to reward and reinforce the good behavior after it “sees” the dog comply. Early on, the device gives the dog a treat unprompted, to get it comfortable with the machine (which also helps keep the dog in view and promotes the “watch” command).

It also ejects a treat when the dog sits or stays unprompted, before issuing commands, to on-ramp the dog into the process.

“Humans might practice a hundred times with messy human repetitions of those behaviors,” Honchariw, a Google veteran and shelter volunteer, told Built In. “We’re using the near-infinite time we have to work with your animal while you’re away to put up 10,000 repetitions, and in a fun way for your dog.”

Honchariw — a former product strategy point person on Google’s TensorFlow team — and his team of animal behavior specialists, computer vision engineers and software engineers spent some two-and-a-half years developing the machine, called Companion Pro, streamlining the hardware and building and fine-tuning the vision model. The company recently shifted to early access and is taking reservations for Quarter Three. It’s also given units to several experts who study separation anxiety, including the veterinarian and behaviors teams at the San Francisco chapter of the ASPCA, which shares premises with Companion.

How to Train a Dog-Training Model

Companion isn’t the first to attempt introducing technology into dog-training and treat-tossing. Petcube has built a devoted following with its app-controlled remote camera-meets-treat dispenser. And researchers at North Carolina State University unveiled in 2016 a computerized dog harness that issues treats when a dog sits. You may also recall that IBM in 2017 patented a dog-sitting drone, which, unsurprisingly, never really got off the ground. Down in the dregs, there’s also anti-bark shock collars, but the less said about those, the better. Regardless, the work of teaching Fido remains largely un-automated.

But with (relatively) low-cost GPUs and depth cameras now able to operate at the edge, Honchariw saw a lane for more advanced, deep learning-based approaches. The computer-vision neural network models were trained on Google Cloud TPUs and they run TensorFlow Lite (the mobile version of TensorFlow) locally in each device on Edge TPUs — Google’s inference-running Tensor AI circuits, famously tiny enough to fit two on the head of a penny.

“Once we were confident in our ability to understand a dog’s behavior in real time, we started reacting to that behavior to create interactions.”

The long work of training the model began with mapping out all the various “signals” they needed to track and understand. Companion’s animal behavior experts “listed all the body postures and vocalizations that we wanted to collect to be able to understand dogs’ readiness for training,” wrote Companion computer vision engineer Michael Wang and product manager Noémie Guérin in a TensorFlow blog post. “Once we were confident in our ability to understand a dog’s behavior in real time, we started reacting to that behavior to create interactions” — that is, the various commands.

This isn’t the first time computer vision has gone to the dogs. The long-standing object-detection algorithm YOLO (“you only look once”) has been used to have AI differentiate between dog breeds, for example. But Companion needed to go further — analyzing posture, motion, ear and tail movement, distance. There wasn’t much out there that was directly helpful.

“We had to pioneer a lot in terms of what signals we thought were important, and then how do we use the existing off-the-shelf algorithms to detect those signals and create the corpus of data we need to come up with our own labeled data set of all environments and all breeds,” he explained. The latter, in particular, is no easy challenge — think about how different a mastiff looks from a teacup terrier. “Dogs are one of the most visually diverse species on the planet, in terms of size, color, texture, hair reflectivity, breed,” Honchariw noted.

With units now in the field, Companion is set up for a data-flywheel effect. Data-sharing is opt-in only, to protect privacy, but users can allow their video data to be fed back into the algorithm, which should help the machine perform better for that specific dog and environment.

Still, Honchariw sees room to advance, considering the computer vision aspect is the only AI application currently within Companion’s device. “I'm excited for how much room we have in our stack to go even further with the technology,” he said.

The hardware, on the other hand, is charmingly workmanlike. CompanionPro uses “right out of the box” Intel RealSense cameras to process images. “We try to keep the hardware as dead simple as possible,” he said, adding that the startup considers itself “a software company that has to manifest what it does through hardware.”

Still, Companion does face a unique hardware challenge: The device has to be dog-proof. Dogs dealing with separation anxiety have been known to pee on stuff, claw and gnaw. To that end, the devices are encased in sheet metal, designed to withstand a hound’s tooth, but shaped in a way that a dog shouldn’t damage its teeth or gums if it does act out and bite down.

There’s also a built-in accelerometer to detect if it’s being jostled.

So far, Companion has only lost one of its treat-dispensing devices to a dog, and that was an early prototype lost to a dog with many behavioral issues. “It turns out that if you’re fun for the dog, the dog doesn’t tend to chew on you,” he said.

Learning New Tricks

Companion Pro is still a puppy in terms of time spent in the field, but it appears to be performing well so far. Product manager Noémie Guérin and the company’s head of animal behavior (a former president of Canine Companions for Independence) partnered with two veterinary doctors from SFSPCA to document the device’s effectiveness.

The team incorporated Companion Pro into the conditioning program of a nine-month-old dog that had behavioral problems. The dog was hyper-attached to its owner and suffered “severe” separation anxiety, and wasn’t responding to medication or behavior modification therapy. But the dog’s symptoms reduced “significantly” within 12 weeks of adding the device into the dog’s therapy, according to the case report, which was peer-reviewed and accepted by the Journal of Veterinary Behavior.

Still, the team is already thinking about what new tricks it can teach the device. Honchariw envisions dozens of future features. He floats the idea of adding sounds that can help desensitize dogs to various noises, such as bustling streets or newborn children, and imagines applications related to gait analysis and well-being, a surprisingly rich subfield in AI already.

There might even be a COVID-19 application. Researchers in the past have trained dogs to use their olfactory might to sniff out malaria, prostate cancer, diabetes and other diseases. It’s not yet clear if COVID has a distinct smell, but other respiratory diseases do alter body odor — a fact that has prompted researchers to study whether dogs might be able to scent-detect the disease.

Researchers at the highly regarded Bay Area scent-training organization Dogs4Diabetics are among those studying the potential, with funding by pet-food powerhouse Nestlé Purina Petcare. Companion is also working with Dogs4Diabetics, with the hope that, if dogs can play a role in detection, its technology can help ramp up training. That’s a lot of conditionals to be crossed, but, if nothing else, it provides a yardstick for the ambition around the tech.

Right now, Companion Pro is very much aimed at, well, pros. Early subscriptions and pre-orders are going to animal behavior researchers, working-dog trainers and shelters. (The device is rent-only and starts at $200 per month, though Honchariw adds the company takes no profits from nonprofit users, as rescue organizations usually aren’t exactly swimming in surplus cash.)

So, no, Companion Pro won’t help my Kirby, or your stressed pup, but Honchariw believes his team will someday usher in a consumer-friendly application of its tech, however far down the road. “It’s going to happen for sure,” he said. “It’s just a matter of how quickly the cost comes down, which is something we’ll always be working on.”