Wall Street is one of New York’s most iconic fixtures, and is a main reason why the city is known as a mecca for finance and investing. But there’s a new kind of investing percolating here, and it involves more than just buying stocks in publicly traded companies. These days, NYC tech startups are letting just about anybody invest in just about anything — from NFTs, to real estate, to a lunar meteorite.

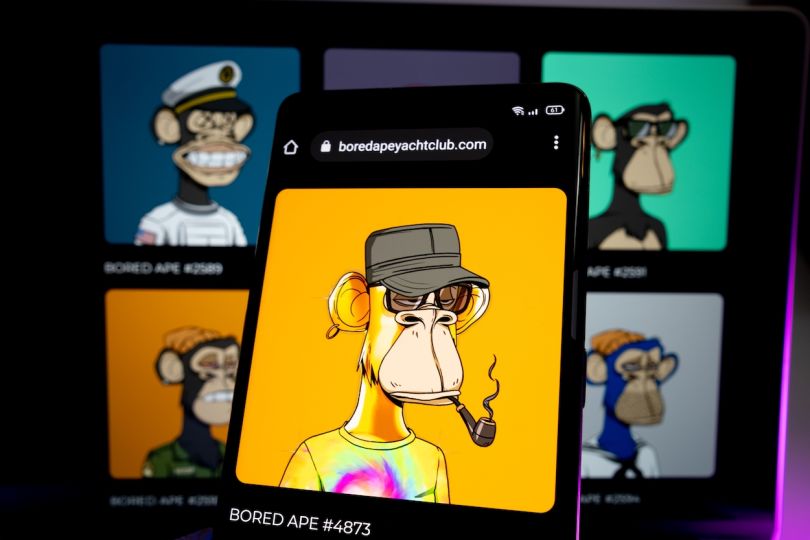

Of course, the crypto hype-train has been merrily chugging along for a while now. Investors poured a record $21 billion into the space in 2021 alone, according to Crunchbase data, with local standouts like Chainalysis, Gemini and BlockFi raising massive funding rounds — and hitting monster valuations. Not to mention Coinbase’s market debut at an eye-watering $85.7 billion valuation. NFTs are on everyone’s minds, too. Even the New York Stock Exchange itself has taken an interest in them, along with celebrities like Lil Nas X and Dolly Parton.

“It’s a white hot industry,” Yash Patel, a general partner at Telstra Ventures and avid backer of crypto innovation, told Built In. “There’s just too much money at stake for anyone to ignore — investors and consumers alike.”

Indeed, cryptocurrency and non-fungible tokens have essentially become mainstream, but they are by no means the only alternative assets having a moment right now. In fact, there’s a whole ecosystem of them — and many are rooted in industries that go back centuries.

Take Masterworks, a New York-based startup that lets users buy fractional shares of art by icons like Banksy and Picasso. Founder and CEO Scott Lynn is a longtime art collector, and came up with the idea for Masterworks when he noticed that his collection was appreciating in value. He decided to do more research into whether art could have similar investment characteristics as other asset classes, which involved going through thousands of paper and digital catalogs of transactions to determine how the art market has performed over time.

“What differentiates art from a lot of the other alternative investments — things like crypto and NFTs — is that it has existed for centuries, it’s just that it was not accessible.”

In the end, Allen Sukholitsky, Masterworks’ chief investment officer, says this process showed that the entire art “universe” — master paintings, impressionist paintings, modern art, contemporary art — had returns of “mid-single digits,” maybe 7 percent, over time. But the appreciation for contemporary art (the area Masterworks focuses on the most) has an annual rate of about 14 percent. For reference, the stock market appreciates at about 10 percent, so it turns out art is pretty attractive from an investment perspective.

Masterworks allows people to buy shares of these high-value paintings by securitizing them — a process that is similar to when a company goes public and issues shares to investors. And business has really taken off. The four-year-old company raised a whopping $110 million Series A round back in October at a pre-money valuation of more than $1 billion, signaling the massive growth potential of the alternative investment space.

“Undoubtedly there’s been a significant amount of growth in new alternative investments,” Sukholitsky told Built In. “What differentiates art from a lot of other alternative investments — things like crypto and NFTs — is that it has existed for centuries, it’s just that it was not accessible.”

A Look at ‘What Else Is Out There’

Like a lot of executives in this burgeoning industry, Sukholitsky comes from a fairly traditional investment background, and has spent much of his career at legacy firms like Goldman Sachs and Citi Private Bank. At first blush, you may not expect a person with this kind of pedigree to wind up at a place like Masterworks — even Sukholitsky felt that way when he was first asked to come on as CEO. He spent years in traditional investment management, researching “every asset class under the sun,” as he puts it. And all the while there was this $1.7 trillion asset class “sitting under [his] nose” that he had never considered as a viable investment option before. It was a game changer.

“The investment management industry has been operating with pretty much the same, let’s call it, five to 20 asset classes that they’ve been using and building portfolios with for decades. It’s just kind of gotten to the point where institutions want to expand beyond those same investments that everyone’s basically been considering for decades now, and thinking outside of the box,” Sukholitsky said. “It’s almost like the investment community just became so saturated with a lot of the same types of investments for so long that, little by little, there started to become this greater interest in what else is out there.”

“It’s almost like the investment community just became so saturated with a lot of the same types of investments for so long that, little by little, there started to become this greater interest in what else is out there.”

As it turns out, there’s a lot out there. StarStock, the “stock market for sports cards,” got an $8 million investment from Andreessen Horowitz and several angel investors including NBA All-Star Trae Young and Twitch co-founder Justin Kan. Alt, another place to invest in sports cards and other playing cards, raised $75 million from VC firm Spearhead, along with Alexis Ohanian’s Seven Seven Six and a smattering of pro athletes. Over the next few years it plans to roll out other asset classes to support everything from watches to NFTs to even LP interests.

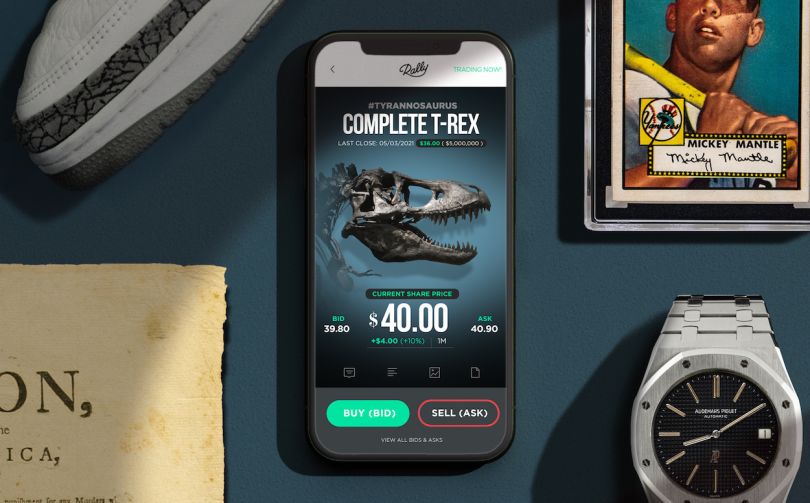

Meanwhile, Rally is on a mission to make “everything in the world” a tradable asset by taking high-value, illiquid assets and turning them into securities that non-accredited investors can invest in. As its name suggests, Rally got its start with collectible cars. Now, CEO George Leimer says it has about 400 securities on its platform for all kinds of asset classes — Pokémon cards, rare books and documents, dinosaur bones, a lunar meteorite. It all comes down to what a given investor is interested in.

And these investments aren’t just fun and games either, there’s some real money to be made on Rally. For instance, about a year ago Rally offered a rookie card of soccer legend Pelé for about $400,000, and just sold it for $1.3 million, a record-breaking price for the industry. All of the investors in that card got governance over whether to take the deal or not, and then got a cut of those profits.

“That just shows the viability of the platform,” Leimer told Built In. “It’s pretty vibrant in terms of both the level of investment on the platform, and just the cool stuff that’s come to the platform.”

Rally is one of many companies offering these types of investment opportunities, and a lot of them are based here in New York. “This is where all the smarts are and where all the brainpower is around finance,” Leimer added, likening NYC to what Silicon Valley felt like in the late ‘90s and 2000s when companies like Facebook and Google were being created. “This is where the center of gravity is.”

Yet, another local success story is Yieldstreet, which provides retail investors with access to alternative investment classes like real estate, fine art, legal finance and commercial loans through fractional shares. The startup raised a $100 million Series C last June and, since then, founder and CEO Milind Mehere says it has doubled its team and launched several new products, including an art equity fund, a crypto fund, and a real estate investment trust. All of this is in an effort to help more people get access to assets that were previously reserved for the “top 1 percent.”

“If you’re working with a wealth manager or financial advisor to get into the types of investments that Yieldstreet offers, you would have to put in $250, $400 million minimums. How many of us can do that?” Mehere told Built In. Yieldstreet remedies this by offering fractionalized investments, allowing people to enter this space without needing hundreds of millions of dollars to do it.

No Longer a Rich Person’s Game

This concept of accessibility and democratization is at the core of a lot of these kinds of companies, but it’s especially important to Mehere.

After immigrating to the United States as a student, he had a very successful career, and went on to co-found Yodle, an adtech startup that scaled to $200 million in revenue while he was working there. On top of that, Mehere had done what a lot of people are told to do when it comes to investments — he adhered to the 60/40 investment model (a longtime strategy that some experts now say is dead), invested in bonds and stocks, and put money in his 401(k). Still, when the global economy tanked in 2008 amid the housing market crash, Mehere says 50 percent of his savings went with it. After meeting with his financial advisor, he learned that, even though he was pretty well-off financially, he still wasn’t considered wealthy enough to invest in other kinds of assets.

This experience, plus the mushrooming online investment space, is what inspired Mehere to create Yieldstreet. And he thinks it’ll alter the entire investment landscape for good.

“I think alternatives are going to go mainstream. And they’re going to become a core part of everybody’s portfolio in the next five years,” he said. “Consumers want a seat at the table. When people think about how outdated the 60/40 stocks and bonds portfolio model is, and when you know that the ultra-wealthy have almost 10 times more exposure to alternative investments, most consumers are saying ‘Why not us?’”

“We fundamentally believe that investors of all stripes have access to the same types of investments.”

This is what Masterworks is after too. In fact, Sukholitsky says Masterworks’ rapid success speaks to how powerful the idea of democratization is — especially in the investment space, which for so long was considered a playground solely for the upper crust.

“What’s interesting about art is that art was originally really only accessible to wealthy individuals, right? You had to have millions of dollars just to buy a single painting, so if you wanted to buy multiple paintings you would have to have even more millions of dollars to buy several. Where we went from there, was straight to making paintings available to self-directed investors all over the world,” he said. “We fundamentally believe that investors of all stripes should have access to the same types of investments.”

Of course, alternative investments companies are coming on the scene at a time when the wealth gap between baby boomers and young millennials and Gen Zers continues to grow wider. Although millennials dominate the workforce, they are ten times poorer than boomers, due largely to the Great Recession of the early aughts. Yet, millennials and Gen Z have become a growing force in the investment space, and these alternative investment companies are trying to capture that younger market.

“All of these things are built around who I am and what community I’m a part of. It says something about who you are.”

“I think more and more people are looking for something else besides what their parents told them was an investment strategy. It used to be you have a 60/40 portfolio, and you eventually buy a house and all these sorts of things,” Leimer said, but that “doesn’t really hold” for Rally’s average demographic, which is people in their mid-20s to early-30s. “That group is thinking about things from trading cards, to wine, to sports memorabilia, to cars, to NFTs. They’re thinking about those things as investments.”

He added that these investments are more than just a money-making opportunity. Alternative assets give users an opportunity to create an identity in a way traditional investments never could. “People come to [Rally] because we have an asset that they’re passionate about, and they think it’s cool to own a share of that asset.”

As far as Leimer sees it, people on Rally treat their assets as more than just investments, but as a “manifesto about who they are.” Indeed, if you walk into a cocktail party and tell people you own shares of Apple stock, people are most likely going to shrug and say “so what.” But if you walk into that same party and say you own a piece of the Declaration of Independence, or a prototype of the 1972 Nike Moon Shoe, of which only 12 exist, you’re going to turn some heads. “All of these things are built around who I am and what community I’m a part of. It says something about who you are,” he continued.

Toward a Decentralized Future

This speaks to the overall ethos of Web3, a new iteration of the internet that is based on blockchain technology — thus enabling alternative investments like cryptocurrency and NFTs, as well as (eventually) the metaverse.

Consider it this way: Web2 — the web we know and (sometimes) love today — is really centered around user generated content like YouTube videos, Facebook statuses and Reddit memes. Regular people can contribute whatever they want to this vast digital landscape — sometimes they get famous, sometimes they get paid, but none of that is a given, and ownership is murky. This is all changing with the advent of crypto, blockchain, NFTs and the larger Web3 space. In this new iteration of the internet, there’s a much bigger focus on this content being owned, rather than just being consumed.

“It really gives consumers ownership of, effectively, their own identities and their own transactions. And not just as consumers but as content creators,” Telstra Ventures’ Yash Patel said. “With all of this decentralization happening, it’s really truly giving ownership back to the participants in this whole ecosystem.”

And people seem to be eating it up. The crypto market alone was recently valued at a whopping $2 trillion. And, although they haven’t really existed in the larger public consciousness for very long, sales of NFTs exceeded $17 billion last year — a huge leap from the $82.5 million sold in 2020.

“The way these things go is it starts out with a movement at the retail level, so to speak, and then it ends up institutional.”

Meanwhile, some of the most prominent players in venture capital are betting big on Web3. Paradigm closed a massive $2.5 billion crypto fund in November, and veteran investor Katie Haun recently raised a $1.5 billion crypto fund just months after splitting off from Andreessen Horowitz — making it the largest fund ever by not just a solo woman venture capitalist, but a solo venture capitalist, period. Her firm Lightspeed Ventures also appears to be bullish about NFTs specifically, having recently invested in top players like OpenSea and Autograph. Plus, speaking of Andreessen Horowitz and NFTs, about a half-dozen members of the VC giant’s most prominent investing team (including Marc Andreessen himself) recently backed a $30 million fund devoted exclusively to buying and holding NFT artwork.

Even Telstra Ventures decided to switch gears from more traditional investments and take a harder look at this flourishing industry, particularly crypto exchange FTX. Patel has since invested in two of FTX’s most recent rounds on behalf of Telstra Ventures, deeming crypto and NFTs as “where the future is.”

Alternative assets of all kinds will continue to be a big part of that future, coming away from the fringes and into the spotlight on arguably the world’s most important financial stage: New York City. And as people from all walks of life continue to find new ways to monetize their most niche interests, Rally’s George Leimer predicts this industry is “here to stay.”

“The idea of people taking things that have traditionally been assets that they either can’t access or can’t control, and bringing them into their control in some way shape or form, is a trend,” he said. “The way these things go is it starts out with a movement at the retail level, so to speak, and it ends up institutional.”