Earlier this year, a doctored image of Oprah Winfrey shouting: “You get a folder. And you get a folder. We all get folders!” cruised around the internet as a show of support for an unlikely recipient — a content management platform created by the Chicago software company Otus.

Chief Operating Officer Keith Westman said the meme first caught hold in Wichita, Kansas, where the platform is helping teachers organize and deliver lessons, grade tests automatically, send announcements to families, and align their instruction with state and national standards.

Otus is banking on the platform to fill a gap in a crowded edtech space, where teachers, already under pressure to help their students meet the requirements of high-stakes standardized tests, are feeling increasingly pinched by the weight of administrative tasks and the demands of learning and integrating new software packages.

“What our co-founder Chris Hull saw, and what Otus was born out of, is the amount of time that was being spent in the classroom on multiple platforms. Logging in, creating your avatar, setting the background up. Time that takes away from what the purpose of being in a classroom is: connecting with people,” Westman said.

Operating from 1000 West Fulton Market in the West Loop, Otus was founded by two enterprising social studies teachers from Elm Place Middle School in Highland Park: Chief Product Officer Chris Hull and Pete Helfers, who is now director of innovation at Gurnee School District 56.

CEO Andy Bluhm provided the seed funding.

“What our co-founder Chris Hull saw, and what Otus was born out of, is the amount of time that was being spent in the classroom on multiple platforms.”

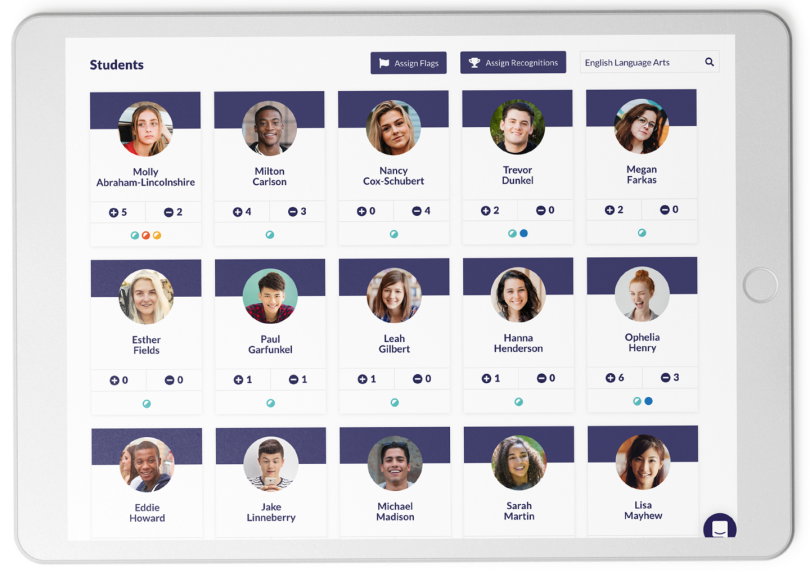

Unlike gaming-style education platforms, such as Legends of Learning and Learning A-Z, Otus doesn’t create any content. The web and mobile platform functions as a data management and information sharing portal, housing disparate pieces of information — from state assessments and at-risk reports to Tier 2 intervention documents and grading rubrics — in a single location.

At a cost of roughly $10 per student, per year, schools can license the platform to replace or integrate a raft of disconnected edtech tools — and, in turn, save time for educators to focus on the human side of teaching. For Otus’ product team, constant communication with users has been core to the process.

We asked Hull and Westman about the user testing strategy that has helped the company expand from an iPad-only app to a multi-platform service with more than one million registered users.

OTUS’ beta users were Hull’s students & colleagues

The idea for Otus was born after Hull and Helfers secured a grant from the 112 Education Foundation of North Shore School District 112 to purchase an iPad for each student in the school’s social studies department. Like many one-to-one programs, the program was well-intentioned, but plagued by operational hurdles, not least keeping the rising sea swell of digital information under control.

“Everything became more splintered to where information was no longer living in a teacher’s notebook or, you know, filing cabinets. Instead, it was being spread across the internet,” Hull said. “Where was the place where you could see a student’s attendance, their behavior, their class work, their interests, their passions, their test scores, their projects — all of it? We’re getting it all live.”

Convinced there was a better way to sync and manage this information, he met with Bluhm, who had an existing relationship with the Chicago software development company Synvata. In 2014, the company built a beta app for the iPad, which Hull began playing around with in his U.S. history class.

The first iteration had an assessment module, a behavior tracking feature, a class announcement board, a lesson planning function and a way to grant recognition to individual students. Hull was pleased with its performance: Not only was the app taking the weight off his administrative responsibilities, it was creating a new venue for students to interact with one another directly.

“There’d be a question on the board, and students would share their answer in a blog,” Hull said. “All of a sudden this information was being captured so students could share their ideas in real time with the class. I could also have them comment on each other and we could really begin to have a dialogue.”

At first, the platform’s capabilities were fairly limited. But while Otus didn’t offer any original content, it served as a gateway to learning resources. A teacher could put together a lesson module on the Civil War and differentiate the instruction by choosing media curated to students’ interests and learning styles: YouTube videos for the digitally inclined, Walt Whitman poems for the literary minded, graphs and charts for the math geeks.

“All of a sudden this information was being captured so students could share their ideas in real time with the class.”

“Then students could submit everything, their videos and their scripts, and I could grade groups and individuals in a really efficient way, all while the social studies standards I was tracking were automatically being tracked as well,” Hull said.

He and Helfers began sharing the software with their colleagues for free, and most of the product’s early user feedback came informally. The two partners culled the best ideas from their colleagues and refined the platform based on teacher suggestions.

But when Google launched the Chromebook in 2014, the founders knew they needed to grow their user pool and become device-agnostic to remain viable.

“Google came in and pretty much now owns the lion’s share of the K-12 market with their Chromebooks,” Westman said. “So it didn’t take the team long to figure out ‘Hey, if we really want to have this be a successful business in K-12, it can’t be just an iPad app. It has to be something that is web-based.’”

The design and development process also had to change. Gathering ideas from close colleagues was instructive, but had an inherent bias: teachers refrained from giving negative feedback.

“So what really switched things for us is when Otus left Chris’ classroom, and we started going out to other schools and other teachers who didn’t know Chris,” Westman said. “Because then we started getting really honest feedback.”

Otus now tracks user feedback from three main sources: customer insights from client services teams; suggestions introduced by the sales team; and ideas culled from Canny, an in-app chat support service that filters user comments by frequency and relevance.

As the team has upgraded the platform, they’ve tested it among an expanding user pool, first within a classroom, then within a school, then at the district level.

It’s easier to redesign features before they’re actually built

One of the company’s most significant user insights emerged when the system was being integrated in the Wichita School District, a large district with thousands of users. Comments “upvoted” on Canny revealed a recurrent teacher complaint: assessments appeared in a long running list, without clear rules for organization.

The solution to that problem was hardly groundbreaking: a live system of folders modeled after Google Drive. But it met the needs of the end users, for whom Drive was familiar and easy to use.

“All the things within the folder are live. So if an editor has made an edit it is captured,” Hull said. That leaves less room for confusion. “You know back when you had a Word doc titled ‘Final Copy’ or ‘Final Final Copy.’ That’s sometimes what happened with these assessments.’’

As Otus has turned to tools like Google Classroom and Salesforce for inspiration, it has also invited teachers into the design process. Former superintendents, principals, teachers and curriculum directors work alongside technologists brought in from places like Uptake, Peapod, SpotHero, Frontline Education and Epic.

“They are just the best source of, OK, how are people actually using this? Where are the pitfalls? What do we need to know?” Hull said. “And then from there we go and we talk to actual users ourselves. We do interviews, we watch them use the product, and we just continue to try to understand where the product is failing.”

“Frank Lloyd Wright said it’s easier to use an eraser on the drafting table than a sledgehammer on the construction site.”

A team led by Chief Design Officer Jordan Walker create wireframes for new features based on user feedback and vet these ideas in classrooms before they go live. In some cases they record users’ screens, “so we can see where is their mouse going, what are they clicking on, what are they understanding, what are they not understanding?” Westman said.

“Then we go back to the drawing room and say, OK, what do we need to [change],” Westman said. “Frank Lloyd Wright said it’s easier to use an eraser on the drafting table than a sledgehammer on the construction site. He’s right. So what do we need to tweak about these mock-ups?”

Ultimately, Otus strives to prevent what Westman calls “waterfall” design, where a quick hand-off from the design to the development team without regular dialogue leads to a three-month flop.

In fact, before Otus even officially launches a new product feature, it is already being routinely used for several weeks by core customers. This allows users to discover new capabilities intuitively and developers to flag and correct any problems before a high-stakes announcement.

Don’t get too hung up on user personas

Joshua Halverson, a technology coordinator at Wood Dale School District 7 in Wood Dale, Illinois, said the company has been receptive to the district’s suggestions, meeting in person three times per year to hash out concerns. He cites a recent effort to beef up the capabilities of the iOS app as an example of a collaborative process that has improved the platform and led to greater district-wide transparency.

“Most families do almost everything directly through the app,” Halverson said. “Parents used to have to dig for information. The app will be structured more like a Facebook feed. As new information is put in, it will show up as an alert on a wall. Parents can see things as they happen and go there directly.”

“The mobile thing is really, really important. Because it allows you to level the playing field as far as access to information.”

The redesigned mobile app, scheduled to launch this spring, will include a chronological feed of school events to keep parents and caregivers in the loop.

“So if your student was recognized by a teacher for showing a lot of grit, the feed will say, ‘Keith showed grit at 10:30 a.m.,” Westman said. “If the teacher puts an announcement up, saying, ‘Hey, we have a field trip tomorrow,’ that’s the next thing they’ll see.”

In that way, Otus’ insights about users has evolved significantly since the company first discussed what would appeal most to their three main constituency groups — parents, teachers and administrators — and thus, which content would be funneled their way.

“We started with just two things we knew parents really wanted: ‘How’s my kid behaving and how are their grades?’” Westman said.

But that wasn’t enough. Parents wanted to know about assignment deadlines, field trips and fundraisers, and they didn’t want to have to log in to a website to access the information.

“The mobile thing is really, really important,” Westman said. “Because it allows you to level the playing field as far as access to information. If you have parents who don’t have a computer, who don’t have the internet at home, you’re telling them to go log onto a computer and see how their kid is doing. They don’t have that option.”

Think carefully about each ask you make of your users

Citing a report of the edtech company Lea(R)n, Westman says Otus’ framework aims to bring efficiency to the unwieldy data flow within U.S. school districts, which use an average of 703 different edtech products each month.

Analyzing and inputting data across a range of platforms with different interfaces and reporting styles not only takes time away from teachers and administrators — it makes technology seem intimidating and distracting rather than inviting and useful.

The ultimate vision for the platform — to enable all school stakeholders, including families and school leaders, to have real-time insight into how students are doing academically and social-emotionally — appears to be gaining traction. And for Westman, Otus’ star will continue to rise as shared “playlists” of teacher-created instructional packages travel from teacher to teacher and school to school.

Halverson, pleased by the software’s integration in his district, is already seeing these collaborative exchanges happen: “It’s been kind of fascinating to see how teachers make the shift. There was a lot of reluctance at first. Teachers viewed it as one more ball they were juggling. But by learning one additional task, they were able to replace 10 others. With slow and steady progress, many have started to see the benefits.”