If you’re of a certain age and persuasion, there’s a strong probability you can hum the theme to Super Mario Brothers and hear the lilting string of notes when Mario, or maybe Luigi or Princess Peach, eats a mushroom and grows big and powerful.

That’s not only because the side-scrolling console game was so iconic, said Joel Corelitz, an independent composer and instructor at Columbia College Chicago, where he teaches a two-semester course on music for games in the Music Composition for the Screen MFA program. “It’s also because it was played on the most elemental, simple sound sources that you could have. I mean, it was two pulse waves.”

Without getting too deep into the Fourier series, a pulse wave is, essentially, the oscillating waveform available on many synthesizers. It’s the chirpy chiptune you can hear in a Nintendo Gameboy or Commodore 64, the ominous clicking of descending aliens in Space Invaders or the immediately recognizable melody of composer Toshio Kai just before the ghosts are released from their cage in Pac-Man.

Those melodies came from single electronically rendered tones — music stripped bare. Back in the ’80s when they were created, Corelitz told me, there was no hiding behind production. Now, as a video game composer, there are infinitely more possibilities.

“Whether you’re creating sounds for a car or a surgical robot or a game, it’s all about finding the design language of the world.”

Depending on your goal — and the size of your imagination — you can pipe in a guitar melody, a bird call, or the rattle of a machine gun. If your budget is big enough, you can go to Home Depot and purchase metal oil drums, paint rollers, chains and bags of bolts and hit them with hammer just to see what they sound like. That’s what Corelitz did with composer Ludvig Forsell, audio director at Kojima Productions, when the two created the bone-jarring, cacophonous sound design for Metal Gear Solid creator Hideo Kojima’s latest game, Death Stranding.

Over the past decade, music for video games has become big business. Brian Schmidt, writing for GameSoundCon, reports that companies like Blizzard, Bungie, Electronic Arts and Microsoft hire full-time, in-house composers. Game soundtracks are played on services like Spotify and Pandora and broadcast during e-sports events. Composers can even earn royalty payments though licensing agencies such as ASCAP for pieces played on TV and in film.

As interest from publishing companies has grown, video game scores and sound design have become much more ambitious. Kentucky Route Zero, set to electronically remixed bluegrass and described by Wired as the “Best Game of the Decade” is a sort of 21st century reinvention of Southern Gothic fiction, with composer Ben Babbitt cast as Junebug, an android folk balladeer seeking transcendence along the byways of rural America.

For Corelitz, who began his career writing music for commercials at the studio Steve Ford Music and has since worked with large publishers like Sony and Annapurna Interactive, the mode of creation — whether highly stylized with synthesizers and editors like Apple LogicPro, or as naked as the sound of a plucked pine cone — is essential to a video game’s user experience, an embodiment of the visceral feeling the game is trying to capture.

“To put it in a very content-agnostic way, which obviously is not the way I think because I’m a composer, I’m creating sounds: It’s all product development,” he said. “So whether you’re creating sounds for a car or a surgical robot or a game, it’s all about finding the design language of the world. That language has to be compatible with the product and the storyline behind the product, and the way we want the user experience to feel,” Corelitz said.

Manipulating Found Sounds

At its the core, music for video games is about world building. That’s why Corelitz typically approaches projects as a listener first, experiencing the game to understand the tone and themes it is trying to convey and what makes it distinctive.

In the indie-game TumbleSeed, the whimsical creation of developer Benedict Fritz and designer Greg Wohlwend in which a seedling ascends a vine toward a mountain top, he sought to balance sounds found in nature with mystical synth patches — a process that involved the creation of more than 30 different musical pieces.

“Because the visuals are so stylized, I was able to have a lot of creative license about when to represent reality on a more realistic level and when to stylize it in the way that matched the visuals,” Corelitz said.

With his backyard as inspiration, he collected acorns, sticks and bark with his sons, and recorded them as they rolled down slabs of flagstone. After looping the samples through an audio editor to extend their length, he arrived at one the game’s signature leitmotifs: the crisp, tactile sound of rolling seeds, which tracks a character’s movement through the game. Inside his home studio, a cockpit-like assemblage of digital synths, cables, and outboard modular units, he then interlaced these sounds with electronic elements to score the game and create its sonic palette.

Digital vs. Analog Synths

Corelitz, like many composers who came of age in the game console era of the original Nintendo, subscribes to the purists’ school that music should come before tools — not the other way around. In developing the concept for Death Stranding, he explained in Polygon, he did plenty of banging on found objects, like boxes and bins, but he also incorporated these sounds in 10 one-minute compositions, which Sony’s music department edited and used to create sample-based instrument banks.

“I wrote 10 minutes that I knew would end up on the cutting-room floor no matter how good they were,” he wrote. Yet, the sounds and virtual instruments created formed the musical vernacular for the eventual battle system scores of Death Stranding.

“With modular synthesizers, once you unplug the cables, that sound is gone forever. So it kind of keeps you using your ears in a way that I think is really engaging.”

Though newer digital synthesizers allow you to model, edit and save virtually any sound, Corelitz said, there is value in the ephemeral quality of analog ones.

“With modular synthesizers, once you unplug the cables, that sound is gone forever. So it kind of keeps you using your ears in a way that I think is really engaging and brings back some of that magic of when I was first bringing synthesizers into my process,” Corelitz said.

“But isn’t the sound recorded somewhere?” I asked him. “Does it really make a difference how it’s saved?”

“You can’t save the actual sound,” he told me. “The actual timbre that you’re playing is, in some ways, lost forever.”

I thought fleetingly of a photograph and how it’s nothing like the experience of being there. But Corelitz was making a broader point: for a modern composer, timbre is everything: it’s the music’s color apart from pitch, volume or duration. It’s what makes a flute different from a clarinet; what makes the same note sound wildly different when patched through two different signal effects on a synthesizer.

“Now, of course you can get close if you know what you did and you can reconstruct it. But in my experience, there’s so many parameters and there’s so many possibilities that it is very hard to repeat yourself,” he said. “And I think creative people need a reason to implement a method where we avoid repeating ourselves, because it is very easy to get into a rut.”

Implementation: The Layering of Musical Phrases

Repetition of a fashionable sound palette can have advantages for an independent composer working on commercials, where clients often gravitate toward familiar styles. Yet, it can be a dangerous crutch in the world of video game design where there is more of a premium on forging ahead into new territory.

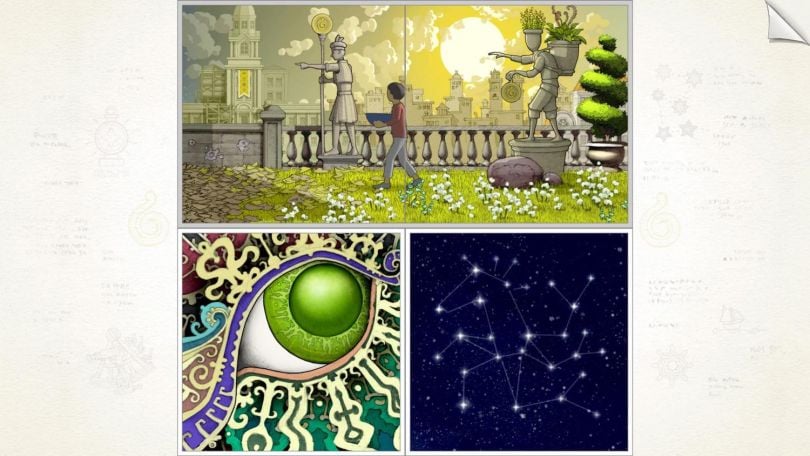

In Goragoa, for instance, another project Corelitz composed for, developer Jason Roberts “wanted music that would blend into the fabric of the game itself,” according to a video preview Corelitz shared with me. Because the puzzle game’s square-tiled interface displays four locations at once, Roberts sought an implementation scheme in which four asynchronous pieces of music would sync when played at the same time.

That was a tricky proposition. Imagine DJing on a table with four records — then imagine something much harder than that, because, as Corelitz said, you’re designing for players, who, through their actions in the game, are dictating when the music will play. Not only did each piece of music have to be compatible with every other piece of music — the layers had to mesh whenever they were introduced.

“It’s not just a piece of music that loops over and over again when you’re in the same area, like in old video games. It’s about implementation.”

Of course, Corelitz wasn’t working on this challenge without a software assist. To get the effect he was after, Roberts developed a scripting engine that controls the way the music is tied to scenes. At the end of the first chapter, for instance, three pieces of music merge in a crescendo that signals to players that they are getting close to solving the puzzle; Corelitz refers to this structured layering of musical phrases as implementation.

In the case of Goragoa that means it’s up to the players, to some extent, to determine the score, which is part of what Corelitz finds exciting about this project and others like it. Unlike linear mediums, such as TV or film, where the score tends to be predetermined, modern video game music “is often presented in a way that can feel alive,” Corelitz said. “It’s not just a piece of music that loops over and over again when you’re in the same area, like in old video games. It’s about implementation and figuring out how the music is structured and sequenced.”

User Interface Sound Is Like Building: Think Foundation, Walls and Finishes

Composition and sound design for a video game interface is a bit like building a house, he said. You start with the foundation, which consists of the most utilitarian aspects: the blips, clicks and bleeps for navigating a menu or making selections; in the case of TumbleSeed, this gets somewhat sophisticated; the sampled sound of a pine cone being thrummed invokes the sound of an Mbira, a traditional African instrument whose percussive, chime-like sound captures the game’s hyper-naturalistic aesthetic.

“You need sounds for when you pick up an item, when you get hit, when you destroy an enemy, things like that.”

If the foundation comprises menu sounds, the walls are the second-tier audio feedback, the aural cues that signal to the player what is happening to their character in the context of the game.

“You need sounds for when you pick up an item, when you get hit, when you destroy an enemy, things like that,” Corelitz said.

The final, and perhaps most crucial, level is the finish: the musical score that serves as the journey’s emotional undercurrent. “That’s the personality. That’s what makes the game feel like its own world with its own feelings,” Coreltz said.

Particularly in games of suspense or stealth, sound cues can be used to teach players things, such as the degree of danger they’re in.

“Generally, there’s a level where the enemy doesn’t know you’re there,” he said. “Then there’s a level where the enemy knows that someone is there, but they haven’t found you. And then there’s another transition when you engage in battle or combat. And you need an implementation system that transitions seamlessly between those layers in a way that feels musical.”

What you don’t want, Corelitz said, is a corny cause-and-effect sequence his students describe as “Mickey Mouseish,” where the player feels like a puppeteer conducting the music.

You also don’t want to step on a developer’s toes — a point Corelitz stresses to his students: “When developers hire a composer, they’re generally looking for tone. It’s up to the developer what goes in and what gets approved,” he said. “They’re the equivalent of a director on a film.”

Sometimes You Need a Sledgehammer

While composers like Corelitz work closely with developers on critical design decisions, where they enter the process varies from project to project. Often it is in the creation of what developers refer to as the vertical slice: the mechanical features of the game exist in wireframes, but the story isn’t fleshed out. Music helps guide this process, but rarely is it the star of the show.

With indie games like TumbleSeed, Corelitz often will take on several roles at once: composer, sound designer, music supervisor, audio producer, guy-with-some-good-ideas at large. But at a large publishing firm like Sony, his role tends to be more limited, with an internal audio department maintaining creative direction over the score, including how long it should last, where the music needs to go, and when it should be delivered.

That’s not to say composing music or doing sound design for games like Hohokum, The Tomorrow Children and The Unfinished Swan is not fun.

“It narrows my focus to the point where I feel like I’ve grown as a composer every time I’ve worked with a music supervisor at Sony,” he said. “I think it’s a lot more rigorous, compositionally.”

To go back to Death Stranding for a minute, it was not only pillaging the aisles of Home Depot to create a symphony of hardware that Corelitz found so exciting — it was the entire exploratory process. At one point, he got to “prepare” a piano with Forsell, transforming the resonance and timbre by placing screws, playing cards and other objects between the strings.

But that wasn’t enough. Forsell was looking for something big, belligerent and epic in Death Stranding — a sound that wouldn’t be easy to forget.

So they turned the piano onto its side and hit it with a sledgehammer.