A few years ago, a German university student wrote a novel and submitted it to Common Voice — an open-source project launched by Mozilla in 2017 to make speech-training data more diverse and inclusive.

The book donation, which added 11,000 sentences, was a bit of an exceptional contribution, said Alex Klepel, a former communications and partnership lead at Mozilla. Most of the voice data comes from more modest contributions — excerpts of podcasts, transcripts and movie scripts available in the public domain under a “no rights reserved” CC0 license.

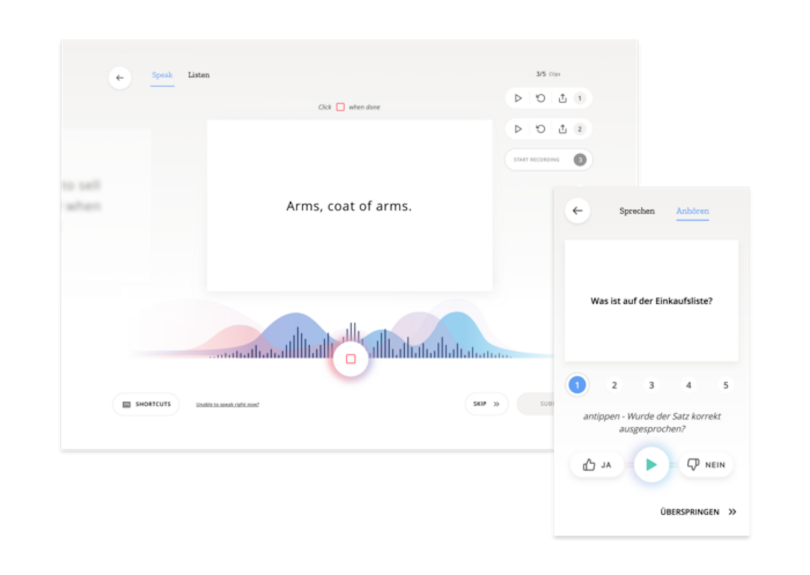

Text-based sentences from these works are fed into a recently launched multi-language contributor platform, where they’re displayed for volunteers who record themselves reading them aloud. The resulting audio files are then spooled back into the system for users to listen to and validate.

The goal of the project, as its website states, “is to help teach machines how real people speak.”

Though speech is becoming an increasingly popular way to interact with electronics — from digital assistants like Alexa, Siri and Google Assistant, to hiring screeners and self-serve kiosks at fast-food restaurants — these systems are largely inaccessible to much of humanity, Klepel told me. A wide swath of the global population speaks languages or dialects these assistants haven’t been trained on. And in some cases, even if they have, assistants still have a hard time understanding them.

“Machines don’t understand everyone. They understand a fraction of people. Hence, only a fraction of people benefit from this massive technological shift.”

Though developers and researchers have access to a number of public-domain machine learning algorithms, training data is limited and costly to license. The English Fisher data set, for example, is about 2,000 hours and costs about $14,000 for non-members, according to Klepel.

Most of the voice data used to train machine learning algorithms is tied up in the proprietary systems of a handful of major companies, whose systems, many experts believe, reflect their largely homogenous user bases. And limited data means limited cognition. A recent Stanford University study, as Built In reported, found that “the speech-to-text services used by Amazon, IBM, Google, Microsoft and Apple for batch transcriptions misidentified the words of Black speakers at nearly double the rate of white speakers.”

“Machines don’t understand everyone,” explained Klepel by email. “They understand a fraction of people. Hence, only a fraction of people benefit from this massive technological shift.”

Open by Design

Common Voice is an attempt to level the playing field. Today, it represents the largest public domain transcribed voice data set, with more than 7,200 hours of voice data and 54 languages represented, including English, French, German, Spanish, Mandarin, Welsh, Kabyle and Kinyarwanda, according to Klepel.

Megan Branson, a product and UX designer at Mozilla who has overseen much of the project’s UX development, said its latest and most exciting incarnation is the release of the multi-language website.

“We look at this as a fun task,” she said.“It’s daunting, but we can really do something. To better the internet, definitely, but also to give people better tools.”

The project is guided by open-source principles, but it is hardly a free-for-all. Branson describes the website as open-by-design, meaning it is freely available to the public, but intentionally curated to ensure the fidelity and accuracy of voice collections. The goal is to create products that meet Mozilla’s business goals as well as those of the broader tech community.

In truth, Common Voice has multiple ambitions. It grew out of the need for thousands of hours of high-quality voice data to support Deep Speech, Mozilla’s automated speech recognition engine, which, according to Klepel, “approaches human accuracy and is intended to enable a new wave of products and services.”

“We look at this as a fun task. It’s daunting, but we can really do something. To better the internet, definitely, but also to give people better tools.”

Deep Speech is designed not only to help Mozilla develop new voice-powered products, but also to support the global development of automated speech technologies, including in African countries like Rwanda, where it is believed they can begin to proliferate and advance sustainability goals. The idea behind Deep Speech is to develop a speech-to-text engine that can run on anything, from smartphones to “an offline Raspberry Pi 4 to a server class machine, obviating the need to pay patent royalties or exorbitant fees for existing speech-to-text services,” he wrote.

Over time, the thinking goes, publicly validated data representing many of the world’s languages and cultures might begin to redress algorithmic bias in data sets historically skewed toward white, English-speaking males.

Licensing and Sentence Collection

But would it work? Could a voluntary public portal like Common Voice diversify training data? Back when the project started, no one knew — and the full impact of Common Voice on training data has yet to be determined — but, by the spring of 2017, it was time to test the theory.

Guiding the process was the question, “How might we collect voice data for machine learning, knowing that voice data is extremely expensive, very proprietary, and hard to come by?” Branson said.

As an early step, the team conducted a paper prototyping experiment in Taipei. Researchers created low-fidelity mock-ups of a sentence-reading tool and a voice-driven dating app and distributed them to people on the street to hear their reactions, as Branson described in Medium. It was guerrilla research, and it led to some counterintuitive findings. People expressed a willingness to voluntarily contribute to the effort, not because of the cool factor of a new app or web design, but out of an altruistic interest in making speech technology more diverse and inclusive.

Establishing licensing protocols was another early milestone. All submissions, Branson said, must fall under a public domain (CC0) license and meet basic requirements for punctuation, abbreviations and length (14 words or less).

The team also developed a set of tools to gather text samples. An online sentence collector allows users to log in and add existing sentences found in works in the public domain. A more recently released sentence extractor gives contributors the option of pulling up to three sentences from Wikipedia articles and submitting them to Mozilla as GitHub pull requests.

Strategic partnerships with universities, non-governmental organizations and corporate and government entities have helped raise awareness of the effort, according to Klepel. In late 2019, for instance, Mozilla began collaborating with the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. Under an agreement called “Artificial Intelligence for All: FAIR FORWARD,” the two partners are attempting to open voice technology for languages in Africa and Asia.

In one pilot project, Digital Umuganda, a young Rwandan Artificial Intelligence startup focused on voice technologies is working with Mozilla to build “an open speech corpus in Kinyarwanda,” a language spoken by 12 million people, “to a capacity that will allow it to train a speech-to-text-engine for a use case in support of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals,” Klepel wrote.

Developing an English-Only Prototype

The work in Africa only scratches the surface of Deep Speech’s expanding presence. According to Klepel, Mozilla is working with the Danish government, IBM, Bangor University in Wales, Mycroft AI and the German Aerospace Center in collaborative efforts ranging from growing Common Voice data sets to partnering on speaking engagements, to building voice assistants and moon robotics hardware.

But it is easy to imagine how such high-altitude programs might come with the risk of appearing self-interested. Outside of forging corporate and public partnerships at the institutional level, how do you collect diverse training data? And how do you incentivize conscientious everyday citizens to participate?

“[It] reaffirmed something we already knew: our data could be far more diverse. Meaning more gender, accent, dialect and overall language diversity.”

That’s where Branson and her team believed the web contributor experience could differentiate Mozilla’s data collection efforts. The team ran extensive prototype testing, gathering feedback from surveys, stakeholder sessions and tools such as Discourse and GitHub. And in the summer of 2017, a live coded version for English speakers was released to the wild. With a working model, research scientists and machine learning developers could come to the website and download data they could use to build voice tools — a major victory for the project.

But development still had a long way to go. A UX assessment review and a long list of feature requests and bug fixes showed there were major holes in the live alpha. Most of these were performance and usability fixes that could be addressed in future iterations, but some of the issues required more radical rethinking.

As Branson explained in Medium, it “reaffirmed something we already knew: our data could be far more diverse. Meaning more gender, accent, dialect and overall language diversity.”

To address these concerns, Branson and her team began asking more vexing questions:

Questions Guiding the Web Redesign

- How could they improve the quality and quantify of the data?

- How could they create a multi-language experience?

Early answers emerged in a January of 2018 workshop. Mozilla’s design team invited corporate and academic partners to a journey mapping and feature prioritization exercise, which brought to light several daring ideas. Everything was on the table, including wearable technologies and pop-up recording events. Ultimately, though, flashy concepts took a back seat to a solution less provocative but more pragmatic: the wireframes that would lay the groundwork for the web contributor experience that exists today.

Designing a User Friendly, Multi-Language Experience

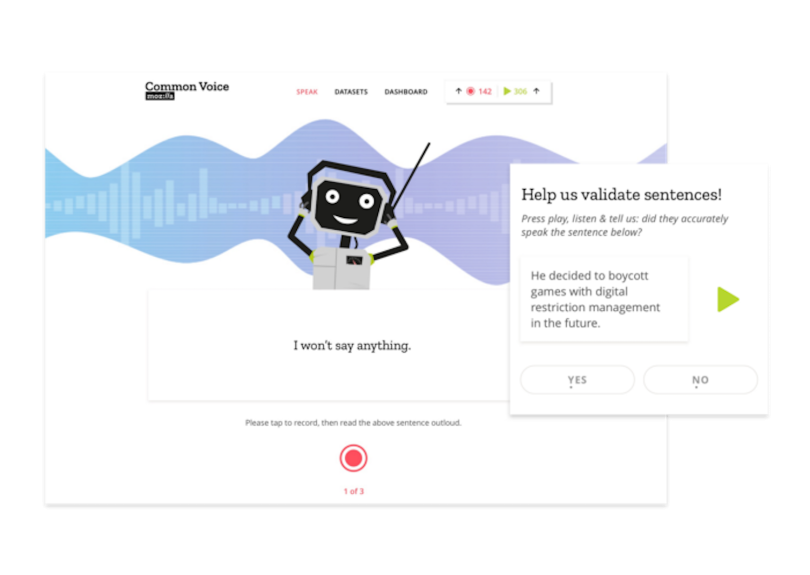

From a user’s standpoint, the redesigned website could hardly be more straightforward. On the left-hand side of the homepage is a microphone icon beside the word “Speak” and the phrase “Donate your voice.” On the right-hand side is a green arrow icon beside the word “Listen” and the phrase “Help us validate our voices.” Hover over either icon and you find more information, including the number of clips recorded that day and a goal for each language — 1,200 per day for speaking and 2,400 per day for validating. Without logging in, you can begin submitting audio clips, repeating back sentences like these:

“The first inhabitants of the Saint George area were Australian aborigines.”

“The pledge items must be readily marketable.”

You can also validate the audio clips of others, which, on a quick test, represent a diversity of accents and include men and women.

The option to set up a profile is designed to build loyalty and add a gamification aspect to the experience. Users with profiles can track their progress in multiple languages against those of other contributors. They can submit optional demographic data, such as age, sex, language, and accent, which is anonymized on the site but can be used by design and development teams to analyze speech contributions.

Current data reported on the site shows that 23 percent of English-language contributors identify their accent as “United States” English. Other common English accents include “England” (8 percent), “India and South Asia” (5 percent) and “Southern African” (1 percent).

Forty-seven percent of contributors identity as male and 14 percent identify as female, and the highest percentage of contributions by age comes from those ages 19 to 29. These stats, while hardly phenomenal as a measure of diversity, are evidence of the project’s genuine interest in transparency.

“We’re seeing people collect in languages that are considered endangered, like Welsh and Frisian. It’s really, really neat.”

A recently released single-word target segment being developed for business use cases, such as voice assistants, includes the digits zero through nine, as well as the words yes, no, hey and Firefox in 18 languages. An additional 70 languages are in progress; once 5,000 sentences have been reviewed and validated in these languages, they can be “localized” so the canonical site can accept voice recordings and listener validations.

Arguably, though, the most significant leap forward in the redesign was the creation of a multi-language experience. A language tab on the homepage header takes visitors to a page listing launched languages as well as those in progress. Progress bars report key metrics, such as the number of speakers and validated hours in a launched language, and the number of sentences needed for in-progress languages to become localized. The breadth of languages represented on the page is striking.

“We’re seeing people collect in languages that are considered endangered, like Welsh and Frisian. It’s really, really neat,” Branson said.

Increasing Gender and Racial Diversity Remains a Challenge

So far, the team hasn’t done much external marketing, in part because the infrastructure wasn’t stable enough to meet the demands of a growing user base. With a recent transition to a more robust Kubernetes infrastructure, however, the team is ready to cast a wider net.

“How do we actually get this in front of people who aren’t always in the classic open source communities, right? You know, white males,” Branson asked. “How do we diversify that?”

Addressing that concern is likely the next hurdle for the design team.

“If Common Voice is going to focus on moving the needle in 2020, it’s going to be in sex diversity, helping balance those ratios. And it’s not a binary topic. We’ve got to work with the community, right?” Branson said.

“If Common Voice is going to focus on moving the needle in 2020, it’s going to be in sex diversity, helping balance those ratios. And it’s not a binary topic.”

Evaluating the protocols for validation methods is another important consideration. Currently, a user who believes a donated speech clip is accurate can give it a “Yes” vote. Two “Yes” votes earns the clip a spot in the Common Voice data set. A “No” vote returns the clip to the queue, and two “No” votes relegates the snippet to the Clip Graveyard as unusable. But criteria for defining accuracy are still a bit murky. What if somebody misspeaks or their inflection is unintelligible to the listener? What if there’s background noise and part of a clip can’t be heard?

“The validation criteria offer guidance for [these cases], but understanding what we mean by accuracy for validating a clip is something that we’re working to surface in this next quarter,” Branson said.

Zion Ariana Mengesha, who is a Ph.D. candidate at Stanford University and an author on the aforementioned study of racial disparity in voice recognition software, sees promise in the ambitions of Common Voice, but stresses that understanding regional and demographic speech differences is crucial. Not only must submitted sentences reflect diversity, but the people listening and validating them must also be diverse to ensure they are properly understood.

“It’s great that people are compiling more resources and making them openly available, so long as they do so with the care and intention to make sure that there is, within the open-source data set, equal representation across age, gender, region, etc. That could be a great step,” Mengesha said.

Another suggestion from Mengesha is to incorporate corpuses that contain language samples from underrepresented and marginalized groups, such as Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives From the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938, a Library of Congress collection of 2,300 first-person accounts of slavery, and the University of Oregon’s Corpus of Regional African American Language (CORAAL) — the audio recordings and transcripts used in the Stanford study.

“How do you achieve racial diversity within voice applications?” Branson asked rhetorically. “That’s a question we have. We don’t have answers for this yet.”