There’s a particularly nasty irony in getting hostile treatment from a wellness app. That’s what happened when Jess Mons, who is non-binary and trans, was faced with a strictly binary gender-identity option at the login screen of a health-focused app. The problems cascaded from there: the app’s messaging, salutations, social grouping and media feed were all personalized, wrongly, to that pigeonholing.

“It was one bad move that just trickled down to a really terrible experience, from all angles,” Mons told Built In.

Mons recalled more bad encounters: A streaming content service, also with a binary form. “Why do I even need to provide my gender for a streaming service?” Mons asked. There was also a dating app that initially allows users to self-identify gender — only to ultimately force a binary, man-or-woman choice at the end of the user flow.

Data and form-design practices on the whole are trending toward inclusiveness, but these outdated, and alienating, digital experiences are still commonplace for non-binary and gender-nonconforming users. In fact, Mons’ own employer was guilty too.

Mons joined market-research platform Dscout in 2015 as a research advisor and almost immediately noticed the problem. The platform prompted its “scouts,” people who participate in paid market studies through Dscout’s app, to Select Gender: Male or Female — no other options, and the field itself was not optional.

Mons, who is now the company’s director of business intelligence, aired concern, but to no avail.

“We were a tiny company then, with around seven people on our engineering team,” they said. “It was kind of a game of resources.”

“I think we had some paralysis around making changes, not necessarily knowing the solution or what a step in the right direction was.”

Other factors stalled potential progress: the destabilizing speed at which the team expanded, a dearth of systems to prioritize different feedback and a lack of clear solutions.

“I think we had some paralysis around making changes, not necessarily knowing the solution or what a step in the right direction was,” Mons said.

Organizations like the Human Rights Campaign have recommendations when it comes to LGBTQ self-identification, but it frames the question in terms of the employer-employee dynamic, rather than user and product. And while conversations around how and when to collect gender-identity data have been ongoing for years within user-experience and data communities, a lack of a single formalized guideline makes adopting an ideal standard difficult.

The tipping point at Dscout arrived about a year ago. It was increasingly difficult to square the company’s internal culture of diversity and inclusion at the office with the external-facing app’s regressive data design. More and more employees raised the issue in product meetings. It was also put to the CEO at one of the company’s monthly town halls, where anonymous questions are answered.

“That really jump-started the process,” Mons said.

Do You Have to Ask?

Dscout soon gathered about 70 non-binary “scouts” for its own study on how to fix the gender-identity question. Knowingly or not, one participant channeled a larger ongoing push within UX and data by asking whether the question even needs to exist. “You should explain why you asked for gender, and if you can’t explain it, maybe you shouldn’t ask for it,” they told Dscout researchers.

The HRC agrees. Its workplace-forms guidelines state, “if the data is not essential, consider removing the question.”

Some civic-data advocates even more emphatically stress the importance of not asking. In a talk titled Protecting Queer Communities Through Data, Chicago-based data scientist Soren Spicknall argues against asking gender-identity questions unless absolutely necessary. His reason is twofold: there’s the initial offense that non-inclusive phrasing may trigger, but also downstream dangers posed if that data is shared with sloppy third-party brokers, even if the phrasing is inclusive.

Dangers range from reinforcing “content bubbles” (where “LGBT+ people are highly likely to see LGBT+-related content and non-LGBT+ people never have to interact with LGBT+-related content”) to serious physical peril, if identifying information and location data falls into the hands of violent transphobes, Spicknall outlines in his talk.

“How about we stop collecting?” he asks. “Instead of putting the burden on a user to fully understand the risks of sharing their highly personal information, let’s put the burden on ourselves [in data science] to treat that information right. If we have no strong reason to collect it, or can’t guarantee its safety, we shouldn’t collect it.”

“Instead of putting the burden on a user to fully understand the risks of sharing their highly personal information, let’s put the burden on ourselves [in data science] to treat that information right.”

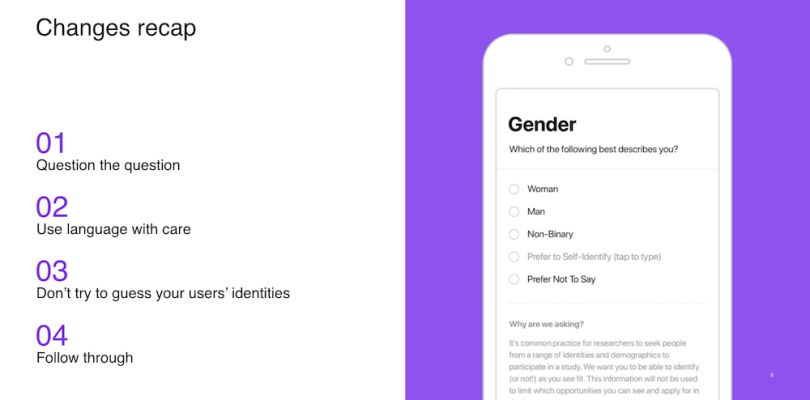

It’s something Dscout weighed heavily, Mons said. They ultimately felt there was a significant reason to ask about gender identity, but they made sure to make the question optional and to include an in-app disclaimer that explains why they asked the question.

The notice reads: “It’s common practice for researchers to seek people from a range of identities and demographics to participate in a study. We want you to be able to identify (or not!) as you see fit. This information will not be used to limit which opportunities you can see and apply for in Dscout.”

“I think we did acknowledge that the way someone identifies their gender identity can be a helpful piece of information, given the types of clients that we work for,” Mons said. Specifically, if researchers are looking for a diversity of perspective, a gender-identity question could help. It could also help fill in representation erasures among marginalized communities.

As creative director of Google’s Creative Lab Tea Uglow, a trans woman, has said, “If the data does not exist, you do not exist.”

Of course, a researcher also has the potential to use that information to discriminate. It’s something Dscout continues to monitor, and so far they haven’t seen a prejudicial trend.

“We’ve been tracking and haven’t seen any downward turn in accepting those applications or participants in projects,” Mons said. “So we’re not seeing repercussions based on gender description [or by choosing not to say.]”

They added: “I hope it indicates that we care more about the interaction and having a good experience than we do about your data.”

Around the same time as the survey improvements, Dscout also removed a mechanism that allowed researchers to filter participants by gender. The move garnered some pushback from at least one client, a consultancy that was targeting people who shop in the women’s department of retailers.

“They were frustrated at first ... but it led to a conversation about what they were really looking for, and who would be the best people to talk to about what they needed,” Mons said.

They drafted questions like: What section of a clothing store do you usually shop in? “Because maybe there’s fathers shopping for daughters, or maybe there’s someone who identifies as nonbinary who shops in women,” Mons said.

“By the end of the client call, they were a lot more excited about that angle. We’re respecting our participants’ identities and we’re also surfacing the correct type of participant who can give our clients the information they want.”

The team spends a lot of time coaching clients to focus more on behaviors, less on demographics, said Abby Hunt, VP of marketing at Dscout. “We do a lot of education on the customer side.”

In Drop-downs, More Is Sometimes Less

As any journalist, UX designer or data scientist will tell you, it’s not just what you ask, but also how you ask it. As Spicknall notes in his talk, Facebook in 2014 added 56 gender-identity options to its drop-down list. It wasn’t just bigoted gender essentialists who scoffed. The people nominally being served had reason to look askance, considering the fact that how we describe gender continues to evolve.

“This attempt is flawed for a number of reasons, chief among them being that what’s considered exhaustive at any given time rapidly falls out of date,” Spicknall noted in his talk. “Since we’re finding new ways to describe gender and sexuality every day when we begin to discuss these things more openly, there’s really no such thing as an exhaustive approach to identity.”

Again, the study participants on the ground were in agreement with the thought leaders at the podium.

“The beauty of expanding language is that we keep getting more and more terms to help people express how they identify the way that they feel,” said one Dscout participant.

Also, it’s just a lot to take in.

“Overall it is beneficial to not have a gratuitous list of a bunch of names to identify as,” said another participant. “I think that can be very overwhelming for everybody.”

“If we list Man, Woman, Non-Binary, Trans Man and Trans Woman, does that separation imply that someone who is trans and identifies as a man is not a man?”

Moreover, some terms aren’t mutually exclusive, and framing them as such is offensive, Mons said: “For example, if we list Man, Woman, Non-Binary, Trans Man and Trans Woman, does that separation imply that someone who is trans and identifies as a man is not a man?”

The study led to a better route, adding a “Prefer to Self-Identify” option, which prompts the user to type in their identity in their own words. “We’re never going to be able to have a list that satisfies everyone, so why not just give them the power to tell us in their own words?” Mons said.

Self-entry also keeps the door open to spot and learn new terms, which could improve the app experience down the line. “If I look at responses in two months and some new term is getting increased usage, maybe that then needs to be added to the four current options [Woman, Man, Non-Binary and Prefer to Self-Identify, plus the decline option,]” Mons said. “That’s great, just as a data nerd.”

The wording of Prefer to Self-Identify is intentional too. Notice there’s no Other option, a design choice that couldn’t be more, well, othering, study participants noted.

Additional subtle, yet significant, changes include rewording the “Select Gender” command to “Which of the Following Best Describes You?”

“We heard that the rigid tone of this felt like we were trying to force participants into a box,” reads Dscout’s report. “By changing the prompt ... we wanted to acknowledge that this is complex and these options may not perfectly fit their identity.”

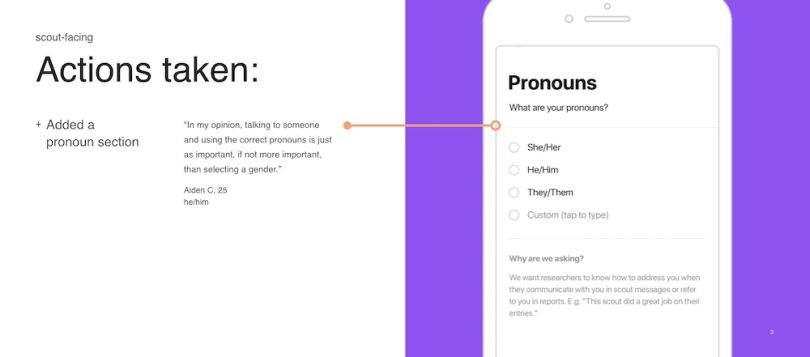

Study feedback also led Dscout to add a pronoun section, which includes a “Custom (tap to type)” function. In the spirit of showing your question-the-question work, it also carries a short “Why are we asking?” explainer. The reason: To make sure no one gets misgendered by researchers for whom they’re running a study.

Don’t Just Include. Protect.

Such inclusive measures are no doubt better than the bad old days of Select Gender: Male or Female. Still, advocates like Spicknall argue that protection, more than inclusion, is the central concern in terms of gender-identity data collection.

“The key thing that I think is almost most important in identity-related data — if somebody declares that they have to collect it — is securing that data. And securing any data is extremely hard,” he told Built In. “But identity-related data can be used for immensely malicious purposes. Malicious actors can out people who aren’t fully out to those around them. Oppressive governments can have certain legal rights over the data of platforms operating in their jurisdiction.”

“Malicious actors can out people who aren’t fully out to those around them. Oppressive governments can have certain legal rights over the data of platforms operating in their jurisdiction.”

Even companies with generally good data practices have suffered leaks or sold data to third parties, he said. “I’m often asked ‘What is a moral framework under which I can still feel good about collecting this data?’ And my answer to that is, ‘Are you absolutely certain that you have done everything possible in your power to secure that data and to produce features from that data that don’t reflect biases about the identities that data covers?’”

Speaking to the issue of protection, Mons notes that research participants share only their name and last initial on the platform, and that they can edit their information whenever they see fit. “They have complete control over [personal identifying information] and can change it whenever,” they said.

Hunt underscored the abstention option and also pointed to sharing restrictions the company self-imposes. “When it comes to our scout profile information, we don’t share that with third parties at all, and we don’t publish individual data publicly,” she said.

If a participating researcher requests users’ profile information, scouts have to sign off before that data is shared. And in those cases, last names are kept confidential. “Any identifying information is kept secure,” Hunt said.

Dscout is also GDPR-compliant and uses Cobalt to run penetration tests on its full stack.

The question of gathering gender-identity information is sometimes framed within the larger push toward so-called data minimalism — the idea that more data collection isn’t inherently better. If “data is the new oil,” well, lots of people are trying to cut down on oil consumption too.

It’d be naive to think Big Tech is losing interest in scooping up reams of data, but Mons sees the pushback sentiment growing at least in some respects: “From a personal standpoint and from experience with designing research with clients, that shift is definitely one that’s happening.”

Mons has seen firsthand working with researchers how data overload can be disabling. “I’ve seen clients get analysis paralysis, where they had no idea where to even go once they had the data,” they said.

That’s of course within the context of market research, not overall web tracking, but it could be arriving more broadly, especially in terms of fatigue at the user level, they said. “Even in general, I think there’s a cultural shift around disengaging from areas where you would provide a lot of information,” Mons said.

Or in other words, asking how much should be asked. And, when asking, doing so conscientiously.