On Valentine’s Day, 2009, Daniel Jue received troubling news from his brother Arthur. Their father, Raymond Jue, who was 72, had suffered a stroke and was lying on his bed, unresponsive. They rushed him to a nearby hospital in San Jose, California, and he was admitted to a patient room for treatment and overnight monitoring.

Prepared to come back and spend the night with their father, Daniel’s brother and mother went to the elder Jue’s home to collect a change of clothes and toiletries. They didn’t have time to retrieve them. As soon as they got inside the house, they heard the landline ring.

“And it was my dad, saying, ‘Help! Help!’” said Daniel Jue, recounting what his brother told him.

They rushed back to the hospital, where Arthur found Raymond on the floor, thrashing back and forth without his gown. The family was apoplectic, appalled their father had been left unattended in such a terrified state. They aired their grievances with the attending care team and hospital administrators, who apologized sincerely, admitting to being short-staffed and overworked.

Mercifully, for the family, Raymond recovered from the stroke and returned home. But over the next seven years, his health deteriorated: He experienced diabetes, episodic dementia and a hard fall that required hip replacement surgery.

The Jues bought their father an apartment across the street from the hospital, with the hope he could quickly access care in the event of a similar emergency. They went through dozens of at-home caregivers, often with disappointing results. They’d hear their father had been taken out for a walk only to discover, hours later, he’d been left in bed all day. They noticed bedsores on his back because caregivers hadn’t rotated him in bed. On at least one occasion, they found him lying in soiled clothes.

The experience was heartrending for the family, and when Raymond Jue died in 2016, Daniel and Arthur decided there had to be a better way to care for the aging.

The two brothers, Daniel Jue, a self-taught programmer who wrote his first computer game at the age of eight on a Radio Shack TRS-80, and Arthur Jue, a human resources executive with experiences at software companies like Twilio and Oracle, teamed up to launch LiveFreely, the health technology company that created Buddy.

What Is IoMT?

A Path for Older Adults to Age in Place

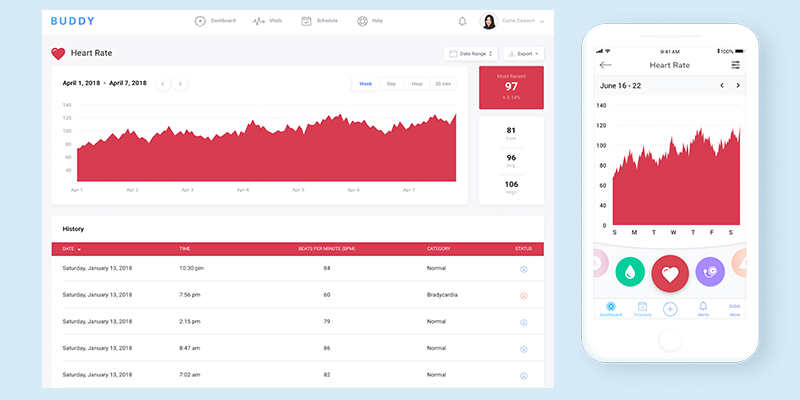

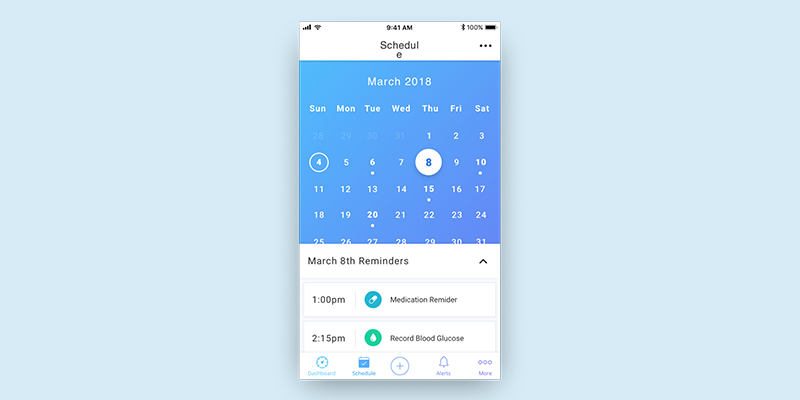

Buddy is a personal monitoring app that, according to Daniel Jue, works with smart wearables like an Apple Watch or FitBit to track vital signs, remind users to take their medications and automatically alert caregivers — and, in some cases, first responders and emergency services personnel — if a user falls, wanders outside a designated safe boundary or feels threatened.

Launched as an iOS app in October 2021 and scheduled for release on Android devices later this year, the app, like a growing number of monitoring apps and wearable devices, responds to the rise in the population of adults over age 65 living with chronic conditions who wish to age in place.

According to the AARP, there are some 55 million people over age 65 in the United States. And a survey of 3,000 people conducted by the organization found 77 percent of adults 50 and over “want to remain in their homes for the long term.”

Mobile apps, such as Buddy, which use AI and machine learning to interpret sensor data from smart wearables, theoretically offer a path for older adults to do that. By providing family members assurance their loved ones are being well monitored and alerting caregivers and first responders of critical health emergencies, such as falls, strokes or heart attacks, the devices offer a way to support older adults living independently.

“That’s what we’re trying to do, and then also take the next step to use machine learning to predict and, hopefully, prevent things from happening,” Daniel Jue said. “We want to move from a model of health care as reactive medicine to preventative medicine.”

“We want to move from a model of health care as reactive medicine to preventative medicine.”

Easing the strain of personal health care management is another benefit of these systems, said Jennifer Kent, vice president of research at Parks Associates, a market research group. By becoming more aware of the correlation between their day-to-day habits and medical conditions, users can understand how changes in sleep, diet and exercise — or a lapse in their medication intake — affect their health.

Beyond that, Kent told me, algorithmic analysis of long-term trends can give health practitioners a clearer picture of chronic disease progression. With access to a near continuous stream of real-time data, care teams can intervene more quickly when signals point to worsening conditions.

“The great thing about modern wearables over traditional PERS [personal emergency response system] devices is the fact that they’re not just focused on emergency situations,” Kent said. “You’re building in layers of health monitoring that weren’t possible before, things like heart rate monitoring and heart rhythm monitoring.”

But for all their potential, remote monitoring devices raise a host of privacy concerns, said Michael Clarke, founder of Pulled, a booking app for home services, including smart device installation. Are users comfortable sharing personal data with loved ones, care providers and, potentially, third-party advertising networks? Are adults with cognitive health impairments doing so voluntarily and with full awareness of the privacy ramifications of their actions? And who are these devices really for — the end users or their family members?

Keeping users safe and informed, while protecting their privacy, is a thin line to walk. In a sense, what makes remote monitoring devices “smart” — that they track and record largely unconscious physiological behaviors — is also what makes them subject to privacy intrusions and abuse.

It’s a classic UX design quandary.

Big Tech Seizes on Home Health Assistants

Fitness trackers, like Garmin, the AppleWatch and Fitbit have been around for some time, but as healthcare investment has shifted toward early diagnosis and prevention, their remote monitoring capabilities have come to be seen as a way to enhance health care quality and outcomes, while taking the strain off overburdened practitioners.

In apparent recognition of the potential for voice-activated home assistants to perform similar functions, large tech companies are investing heavily in the space. Through Alexa Together, Amazon offers a paid monthly service that allows caregivers, with the consent of those in their care, to view a daily log of activities recorded on a supported Amazon home assistant. The service works in concert, for instance, with the Echo Show, a portable HD display screen designed to let users make video calls, watch shows and podcasts, set reminders and remotely monitor their homes.

Amazon has also partnered with Vayyar and Assistive Technology Service to offer wall-mounted and neck-worn fall-detection services as part of the subscription. If those devices detect a dangerous fall, caregivers are contacted via text messages, push notifications and phone calls, and an urgent response feature offers voice-activated access to an emergency helpline.

Amazon, while one of the most active players in the space, is hardly alone. In a New York Times Wirecutter review of smart devices for older adults aging in place, Rachel Cericola writes that Apple HomeKit, Google Assistant and Samsung Smart Things offer similar services. Once connected to a companion iOS or Android app, these smart home platforms let users remotely manage multiple systems, from security cameras and stove timers to lighting systems and fall detection monitors, receiving alerts when something is amiss.

Smaller companies are also entering the fray, Kent told me. In a modern evolution of the panic button, San Francisco, California-based Lively’s Mobile Plus and Wearable 2 devices offer automatic fall detection, GPS tracking and two-way audio communication. And LifePod, a programmable smart speaker, lets caregivers set proactive reminders and check-ins — like, “Jeopardy! is coming on, time to get ready for bed” — by recording their own voices.

Adults age 65 or older appear to be receptive to at least some form of monitoring technology. According to a 2021 Parks Associates survey of 5,000 Internet-connected households shared with Built In over email, 37 percent of adults age 65 or older reported they would be open to purchasing or acquiring “a solution that supports independent living in the home,” compared to 35 percent who said they would be comfortable “moving into a senior or retirement community.”

Other published research by the firm shows 55 percent of U.S. broadband households own a connected health device, and 73 percent of U.S. caregivers say they are likely “to buy an independent living solution for their loved one.”

Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Privacy

Still, Clarke said home monitoring systems lay bare a hornet’s nest of ethical issues, which are complicated by the power dynamics inside families and the fact that devices are often purchased and used at the urging of adult children.

Many of the concerns center on the surveillance capabilities of candid video features. Alexa Together, for instance, offers a Drop In feature that, once activated, lets other users with Alexa devices digitally drop into their homes unannounced, seeing inside through a live video feed.

While users must give consent to turn on Drop In, Clarke told me, some may not be aware of the “always-potentially-on” ramification of the feature or feel under pressure to acquiesce to the preferences of younger family members who appreciate the convenience and peace of mind the service offers.

“There’s loads of concern around eavesdropping,” Clarke said. “Technically, if you just keep pinging [an Echo Show] device, you would be able to keep pulling a video and audio feed into your system.”

Another concern is where the data ultimately winds up. Google restricted the use of third-party cookies on insecure HTTPS connections in Chrome in 2020, and with iOS 14, Apple required users to choose to opt in to share data with third-party apps. But voice-activated home assistants may be a back door for advertisers to collect recorded user data, Clarke said.

“So what Amazon and Google are doing with these devices is, essentially, getting data through voice,” Clarke said. ”When someone opens an app, or searches by typing in keywords on their computer, they’re limited there, but they’re not limited from a voice standpoint. Did you mention in a conversation that you were out of cereal? Did you express interest in buying a new duvet? They can use that information to target you with ads and offers.”

Transparency in Data Tracking and Sharing

Some users seem willing to concede a degree of privacy for the promises of remote monitoring systems. Prolonged health and well-being, the ability to live independently and the potential to save money, Kent told me, hold sway in the minds of users and can outweigh concerns over spying or eavesdropping.

A pilot study of an ambient home-sensing platform deployed in a planned older adult community in central Florida, for instance, evaluated the experiences of 21 adults over age 55, who had sensors installed in their single-resident homes. The integrated system, called HomeSense, used 16 to 20 sensors to track activity in 90 percent of each residence, capturing everything from room entry and exit, to bathroom and refrigerator use, to medication intake and sleep.

Participants in the program were randomly recruited from a test bank of 10,000 older adults living in The Villages, the largest planned community in the United States, who had previously enrolled in a program to self-report their general health, demographic and contact information. All lived in homes with internet access, and were briefed on the study’s aims and the health data being collected. They were given a standardized cognitive assessment and granted consent to have the passive home-sensing system installed in their homes.

After the six-month enrollment period, the study’s authors wrote, “many participants choose to continue” and “retained the sensor system in their homes. … In total, 15 participants have crossed the one-year threshold, seven have been with the program 18 months or longer and four have stayed with the study since inception.”

Buddy has several safeguards in place to ensure the privacy of its users, Daniel Jue said. A consent form compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, assures users and their caregivers (who also must grant consent), their data will never be sold or distributed to unauthorized third parties. An option in the app’s settings allows users to delete all data, if they become concerned it’s being misappropriated or they’re simply no longer comfortable having it exist in cyberspace.

“As soon as we started to say ‘camera’ ... our senior focus groups were like ‘No, no, no.’ They want to have their sense of privacy, as well as their sense of dignity.”

The app is also deliberately limited in the type of information it collects, Jue added. It does not retrieve or store any visual data from built-in smart watch cameras, an idea that was initially explored by the design team but later nixxed when user testing revealed it to be a hard red line among many older adults.

“As soon as we started to say ‘camera,’” Jue said, “our senior focus groups were like ‘No, no, no.’ They want to have their sense of privacy, as well as their sense of dignity.”

Still, many of the app’s most compelling features require users to hand over personal information to function effectively. The extent to which devices like Buddy can provide transparency in consent agreements and give users granular control over the type of data being shared, Jue said, will likely determine whether they earn users’ trust and succeed in the marketplace.

Machine Learning and Fall Risk Detection

During an interview over Google Meet, Jue shook his Apple Watch, installed with Buddy, to activate the device’s fall sensors and generate “a false positive.” A message reported that “a fall has been detected, please open the Buddy app and call for help.” These erroneous notifications are undoubtedly a source of frustration, but, for Buddy users, Jue said, they become less frequent after a few weeks. A fall detection algorithm uses machine learning to improve the app’s ability to distinguish concerning falls from non-threatening ones as user feedback confirms or invalidates the app’s preliminary conclusions.

“We can tell the difference between what I call ‘plopping’ — somebody sitting down really hard — versus another common situation, someone trying to get up from the chair and sliding down, versus a serious fall,” Jue said.

A gait detection feature that measures the distance of a user’s stride, their walking speed and the pressure under each foot is a key factor in preventing falls, he told me. If a user’s gait changes by more than 20 percent from a baseline calculation made during onboarding, users and their caregivers are alerted of a fall risk. So far, no actual falls have been detected among the app’s 2,000 users, which Jue regards as a sign of the app’s success as a preventative measure.

“So we’re improving fall detection, but the end goal is for users not to fall at all,” he said.

In line with that objective, a Bluetooth-enabled device that attaches to a user’s cane or walker can be synced with the Buddy app to let caregivers know whether a mobility device is being regularly used. Users who meet established benchmarks receive perks like Amazon gift cards, a sort of gamified reward for maintaining safe mobility habits.

The app also offers an option to track medication use, blood pressure and glucose levels. Through optical text recognition software, a photograph of prescription guidelines from a pill bottle will automatically record recommended dosage levels, set up reminders and check for potential medication conflicts against a U.S. Food and Drug Administration database.

“In our beta, we found that a person’s heart rate spiked at 10 a.m. every morning. And we noticed that is when they were taking their medication. An email was sent to them, saying, ‘Hey, you might want to get that checked out.’ And they went to their physician and found their dosage was not accurate,” Jue said.

Who Are the End Users for Remote Monitoring Devices?

From a privacy standpoint, though, a looming question remains: Who are these devices really for?

In Buddy’s case, sales data offers a fairly good idea of the answer: about half of the app’s customers are adults over the age of 50 and the other half are caregivers.

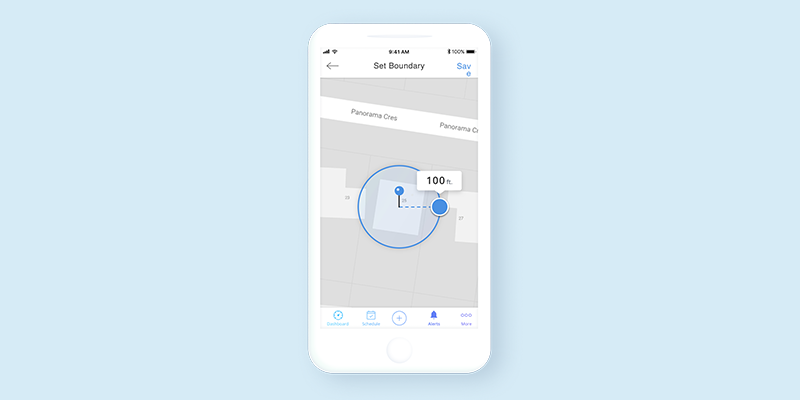

Buddy’s boundary alert feature, perhaps one of the most controversial functions of the app, is where the interests of these two distinct end users, as well as implicated non-users, may be at odds. Using the feature, consenting users can demarcate spherical radii inside which they are presumed to remain for a set period of time — within a mile of their home or office during the day, for instance. Alerts are sent when monitored adults leave or enter designated boundaries.

For caregivers of people with memory loss conditions like Alzheimer’s, these alerts can be a valuable tracking tool, helping to signal when an individual may have wandered and gotten lost.

“One of the hardest things with my father was to allow them to have his freedom, while also being able to maintain the ability to know when he’s wandering,” Jue said. “We created this boundary alert to let others do that.”

One can imagine, however, how some users might view such monitoring as an unwanted form of babysitting. Maybe on a whim, a user wants to join their colleagues for a drink after work. Should their family or caregivers be alarmed that they don’t reenter their home boundary at a designated time? For some cases of memory loss, the answer might be yes. But it’s obviously a touchy issue, complicated by the fact that, for some users, the alternative might be to move from their homes into assisted care facilities.

“One of the hardest things with my father was to allow them to have his freedom, while also being able to maintain the ability to know when he’s wandering.”

Another concern is that the app’s boundary alerts might unsettle caregivers, who view them as a kind of snooping or a breach of trust. Because the feature can track a user’s rough location, it sketches a picture of their whereabouts throughout the day and often, by proxy, their caregiver’s.

“We can also detect movement,” Jue added, suggesting localized activity tracking is another window into caregiver treatment. “For instance, a bedridden patient has to be turned every so often, so they don’t get bed sores. We can detect whether that is happening or not. Little things like that can help to audit their care.”

While all this might sound a bit like Big Brother, it’s important to keep in mind that the app’s capabilities deal with human lives. In a review in the App Store, in which Buddy has a rating of 4.8 out of 5 stars based on 11 reviews, one user wrote, “I signed up for this app for my 87-year-old auntie who lives by herself. One week later she had a heart attack at home. This app detected the trouble and sent me an alert and also 911. She got help within 5 minutes.”

The larger point may be that health care decisions, while deeply personal, are hard to extricate from wider filial and community networks. Boundary alerts, like many of the app’s prominent features, Jue said, are a reflection of his family’s experience and the many ways in which the home and institutional healthcare system failed his father. Before the onset of the stroke that led to his hospitalization, Raymond Jue experienced several undetected transient ischemic attacks, or short-term “mini-strokes.” Reluctant to use his walker, he broke his hip from a hard fall. Later in life, he often wandered from home.

Whether an app or remote health monitoring system could have mitigated any of these events is impossible to say. But Jue believes other families should not be put through such trials. If designers of monitoring software can find the right balance between safety and privacy, the possibility may be within reach.