Filmmaker Daniel Hess first watched Steven Spielberg’s science-fiction adventure Ready Player One on a tablet flying home from a business trip. He liked the movie enough to re-watch it on a larger screen later on.

“The amount of items on the screen, and Easter eggs, and everything else going on — you could really take it all in,” he said. “Whereas on the small screen, it just kind of turns into pixelated noise because there’s so much to be squeezed in.”

With this dual-viewing experience in mind, Hess plans a different approach to the filming of his current project, Sparrow’s Point, which tells the story of the tumultuous last day in a young couple’s relationship.

More closeups will help better portray the characters’ emotions. Pops of color in the sets will catch the eye’s attention on a small screen. Hess wants to shoot at 6k or 8k resolution with an Arri camera for ease of editing. “If there’s something that’s in the frame, that’s messing the view up or things like that, you can crop and get the kind of framing you need,” said Hess, whose company, To Tony Productions, is based in Baltimore, Maryland. “Having that ability to condense down is invaluable.”

It’s no spoiler alert that technology influences movie making and the industry overall. What might surprise, though, is the levels at which tech is permeating the business. The sweeping sagas, to be sure, are streaming, which has sparked what some call a “democratization” of the film industry, and small-screen viewing, which is changing the way filmmakers, like Hess, think about their movies. Smaller, less expensive cameras and a plethora of platforms make it easier for young filmmakers to break into the business.

“I’m trying to use the small screen and theater to my advantage,” said Latoya Flowers, the current Hulu/Kartemquin Accelerator fellow at Chicago-based Kartemquin Films, who is filming Still Searching, a documentary about missing Black women and girls in Chicago. For instance, when researching cameras, she considered people who’d watch on their small phone screens or a laptop’s web browser and film festival showings too.

The Future of Film: VR

She’s also using techniques such as animation to appeal to both large- and small-screen viewers, as well as adding elements such as projection mapping (projecting images onto irregular surfaces) to broaden the story into public spaces, such as installations. It’s a big change from a decade ago, when Flowers launched her career in film. “There are so many more options, which is what I’m excited about,” she said.

Tech Touches

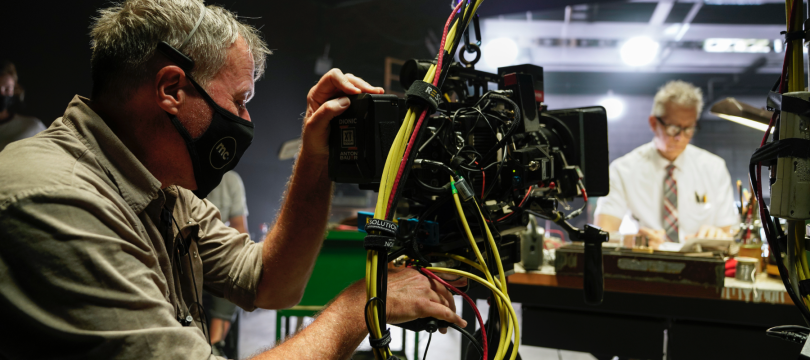

At the same time, behind-the-scenes technology is also revolutionizing, or at least evolutionizing, the industry.

Paula Froehle is directing The Faraway, Nearby, a documentary about the life of physicist Joseph Weber, who worked in the ’60s and ’70s. Traveling back half a century to shoot the film in a period scientific lab wasn’t an option. A recreation of Weber’s lab, complete with a six-ton aluminum bar Weber used in his research on gravitational waves, would have required money that the budget did not have.

So Froehle, in collaboration with Resolution Studios and Miller Creative in Chicago, used Unreal Engine, a tool usually used for video game backdrops, to create a digital facsimile of Weber’s lab. The set is projected onto a high-resolution screen and is tied to Froehle’s camera. “The camera moves in real space with a real actor, who reacts as if it’s a real environment,” said Froehle, CEO and co-founder at Chicago Media Project, a membership organization that supports documentary filmmaking. “It creates a heightened sense of realism that CGI often misses,” she said.

Lighting, angles and other factors can be adjusted via computer, enabling Froehle to do three weeks worth of filming in about five days. Froehle said that to her knowledge, The Faraway, Nearby is the first documentary to use this technology. “It is financially a game changer,” she said. “It’s simpler.”

For actors, expectations — and technology — are game changers. Micro films, a la TikTok and Instagram Reels videos, are changing the expectation of what acting can be, said Vas Provotakis, a Los Angeles-based actor. “It’s a new form of acting that’s a lot more like performance art,” he said. “It’s a lot more about being able to gear a performance to get the most exciting, fast, attention-grabbing sort of character on your phone, so people get drawn in like a minute, and probably less than that,” he said.

Provatakis used an app, ColdRead, to memorize his lines for Hollywood Hopeful, a film that wrapped this past summer. “I’m good with memorization, but I hate it,” he said. Rather than relying on a friend to run lines with or lug a script around, he read the lines to the app, which transcribed and recorded them.

When it came time to learn lines, the app served as a mobile teleprompter and also gave Provatakis cues for his next lines. “It gave me all the preparation I needed,” he said, adding that he learned his lines in about half the time it would have taken using a script or a friend.

Sound and Vision

One ripple effect of tech on filmmaking: Streaming has created a different attention span among viewers. Since 2013, when Netflix began releasing series by season instead of by single episode, viewers have cultivated the patience to watch a multi-episode series. They’ve also gained the power to pause the picture for a snack or break, something possible, but much more difficult and disruptive, in a movie theater.

“The audience is not tied to what we do, and that’s going to affect how we write,” said David Tolchinsky, a professor at Northwestern University and founding director of its MFA in Writing for the Screen and Stage program, who is also a screenwriter and composer. “It’s going to make us think more about drama and conflict and also shorter pieces.”

It’s still lights, camera, action — but much faster to action, Tolchinsky said. “You’re seeing a front loading of dramatic experiences in a way that you don’t necessarily have to do in a theater, but we’re trying to grab people’s attention right away,” he said. He added, though, that an audience does exist for films that unfold slowly, citing Pig as a recent example. “It’s just Nicolas Cage just sitting there with his pig, collecting truffles, and I thought it was absolutely fantastic,” Tolchinsky said.

The Future of Film: Farewell to Mid-Market Movies?

How people listen to movies — on theater screens, home-movie screens or phones — doesn’t matter much to Benn Jordan. “I always want to just live in this fantasy that people are watching or listening to what we’re creating in the most premium environment ever,” said Jordan, a Smyrna, Georgia-based musician and composer. “It’s a delusion, because actually most people are listening to my music on a Bluetooth speaker, or a cell phone, or an iPad or something like that,” he said.

Given the sheer variety of devices on which people consume entertainment, Jordan said there’s no way to ensure that a piece of music sounds good on every device. “So you aim for the best ones, then hope it trickles down to the others,” he said.

Barrier to Entry

“You had to be a genius to make Taxi Driver,” Jordan said. The 1976 film, directed by Martin Scorsese, had a $1.9 million budget, about $9 million in today’s dollars. “You had to be ingenious to pull that off without a massive budget,” Jordan said. “Now, just looking at the budget of what some short films cost, it’s amazing. It’s frankly amazing. You can scrounge up money and make the film you want to make.”

The combination of a lower barrier to entry (smaller, cheaper cameras plus more platforms) and streaming are major contributors to what Jason Cherubini calls the “democratization” of the film industry. “It’s never been cheaper to make a film, it’s never been easier to get a film on a platform,” said Cherubini, chief financial and operations officer at Dawn’s Light Media, a production, consulting and financial services company for media projects.

“Somebody sitting on their couch on a Saturday night has access to every TV show they’ve ever watched in their entire life, and you’re asking them to take a chance on your film instead of something they know they like. That’s a barrier to get over.”

That democratization, though, causes more competition for new filmmakers, on several levels. “Not only are you competing against other independent films and studio films, you’re competing against reruns of ‘The Office,’” he said. “Somebody sitting on their couch on a Saturday night has access to every TV show they’ve ever watched in their entire life, and you’re asking them to take a chance on your film instead of something they know they like,” he said. “That’s a barrier to get over.”

Democratization also filters into what gets made, and by whom, said Gordon Quinn, co-founder and artistic director of Kartemquin Films, a Chicago-based nonprofit producer of documentaries that was founded in 1966. Among its marquee films is the widely acclaimed 1994 documentary Hoop Dreams, which followed the lives of two high-school students who hoped to become professional basketball players.

Hoop Dreams holds its own place in the annals of film tech: It was one of the first feature-length films with theatrical distribution shot on Betacam videotape, one of the first transferred from tape to 16mm film, for the Sundance festival, and then to 35mm for a theatrical release, he said.

“For so long, you had white people telling everyone’s story, and that was a huge problem,” Quinn said. “I think it is exciting to see things shift, where communities and people who were cut off from telling their own stories are now able to get access to the equipment and the platforms to tell their own stories,” he said.

He named two Kartemquin co-produced films, Unapologetic, a film about Black Lives Matter by director and producer Ashley O’Shay, and Jiayan Shi’s Finding Yingying, about a young Chinese woman who arrives in the United States to study and then disappears, as examples. “[O’Shay and Shi] are skilled storytellers and craftspeople who think about how the shot is composed, what they’re doing, what their relationship to their subjects are, and all these things we traditionally thought about,” Quinn said.

The ability to make movies quickly and inexpensively, though, might not be all that good for the art. “The democratization doesn’t mean that everyone should be making a film and telling their own story,” just as not everyone with a pen and notebook should sit down and write a novel,” Quinn said. “That’s not what makes for great storytelling and great literature,” he said. “If it’s going to be a real work, an important work, it’s hours and hours of human labor that goes into making something, into sticking with a story over years,” he said.

The Bottom Line

Tech also touches the financial side of the movie business. In July of 2010, Dawn’s Light Media had a theatrical release planned for Money Plane, an action picture. The movie ended up skipping the theaters and going straight to streaming.

To create buzz and build demand, the distributors launched a viral marketing campaign that included social media plus some of the bigger pop-culture websites, a strategy that dropped the marketing budget to half of the original planned spend.

Movies, Cherubini said, used to depend on theater box office for big profits; now there are other avenues, including buying a new film and watching it on an ad-supported platform. “You don’t need the big marketing outlays to get it onto these screens,” he said.

In the ultimate example of movie democratization, Provo, Utah-based Angel Studios crowdsources equity funding and the green lighting of film and television projects, a move that can help ensure their financial success, said Neal Harmon, co-founder and CEO.

Creators bring a “torch,” or a short video synopsis of their idea, to the studio. Investors — everyday people who ante up, on average, $100 in each project — watch the torch and then vote on whether the movie should be greenlit. A combination of funding and investments gets the films made, Harmon said.

“The competitive factor isn’t the technology, per se, but it’s the people who figure out ways to deliver results with technology better than their competitors do.”

In a typical offering, investors, and there can be thousands of them, get a credit at the end of the film and receive at least 120 percent return on their investment should the film be created and make money. The film’s creators don’t get a financial distribution until investors are repaid, Harmon said. If the film, for whatever reason, doesn’t get fully funded, investors get their money back.

The system creates a built-in audience for the film, as investors will bring friends and family to see a film that has their name on it. It also inspires filmmakers to work harder. “They’re answering to the audience, not a studio,” Harmon said. “Their reputations are on the line and the audience is counting on them.”

So far, Angel Studios has released a handful of projects, including two comedy series, Dry Bar and Freelancers, a children’s series, Tuttle Twins, and The Chosen, a series about the life of Christ. Harmon said that Dry Bar and The Chosen are profitable, and that the other two are on the way to being profitable. “We’re really excited, because the movie industry hits only about 20 percent of the time,” Harmon said. He expects the studio to turn out around 100 projects a year by 2024.

Because equity crowdfunding is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission, Angel created its own technology, including an app on which investors can stream the final products, rather than use existing crowdfunding tech such as Kickstarter or GoFundMe. “The competitive factor isn’t the technology, per se, but it’s the people who figure out ways to deliver results with technology better than their competitors do,” Harmon said.

True, most likely, for every aspect of Hollywood touched by tech.