The first time I tried wearable eye-tracking software I came uncomfortably close to colliding with a car. Not because of the technology — rather because I was fumbling with the gears on a Divvy bike.

Let me explain.

Several weeks ago, the Swedish company Tobii sent me a set of wearable eye-tracking glasses (dubbed the Tobii Pro Glasses 3) and a pocket hard drive containing a lithium-ion battery and a memory card. To test what designers could learn from it, I ran an informal experiment.

While wearing the glasses, I unlocked and rode a Divvy bike — Divvy is the brand name of Chicago’s bike sharing system, which is operated by Lyft for the city’s Department of Transportation — through my home town’s Logan Square neighborhood. After the ride, Mike Bartels, director of marketing research and UX for Tobii’s North American division, helped me interpret the results.

But before we get into the ride and what designers can learn from it, a little history.

What Is Eye Tracking?

Eye Tracking: A Brief History

Eye-tracking studies got their start in advertising but really came of age with the internet. In the early 2000s, Bartels said, design agencies and marketing companies jumped at the opportunity to use mountable auxiliary devices similar to webcams to glean insights about consumer attention. What did people look at on a homepage? How did they navigate a website or browse the internet?

Over the past decade, he told me, as the technology has become more portable and easier to use, it’s been adopted by organizations in virtually every market sector. For instance, over 3,500 companies use eye trackers, according to internal data Tobii shared with Built In. Consumer goods companies like Unilever and Procter & Gamble use eye-tracking devices to understand which package designs retail customers will be most likely to notice on shelves and purchase. Auto companies, such as Toyota, use eye trackers to test the safety of their cars and analyze the attentional patterns of line workers. Google uses them to test the usability of new devices and media.

How Are Eye-Tracking Glasses Used?

Historically, eye-tracking studies have been conducted remotely by focus groups in simulated environments or research labs, but new wearable devices, like eye-tracking glasses, are making it easier for designers and researchers to conduct experiments in real-world settings.

“But the thing that a lot of our clients find most impactful is just, literally, being able to see through the eyes of their users.”

Companies can study, for instance, how a foundry worker pours molten aluminum at a factory or a new user sets up their Super Nintendo in their living room. Watching the actual, lived experience and interviewing users afterwards helps software and operations teams understand how users interact with products, where they are confused or frustrated, and what they are thinking about during the process. This allows teams to improve product safety and optimize usability and performance.

“The most obvious example is probably advertising,” Bartels said. “If you want to understand which version of your TV commercial keeps eyes on the screen for the longest, you can use eye tracking and say, ‘Hey, this ad was associated with a 15 percent increase [in viewing time].’ So that’s one way to use it. But the thing that a lot of our clients find most impactful is just, literally, being able to see through the eyes of their users.”

That’s what I was curious to learn more about. Here’s what I discovered, and what UX designers can learn from more formal experiments with larger groups of test participants.

The Lyft Bike Share Works Well. I Got the Bike Quickly and Knew Where to Go.

The first thing I learned was that Lyft had its act together, even when users — or this user — did not.

As Bartels told me after the ride, my journey required using a kiosk, downloading and using an app, scanning a QR code to unlock the bike, viewing a map of the route, riding the bike and returning it to a new docking station. This entire digital ecosystem has to work smoothly or users will get frustrated, and, potentially, put themselves or nearby motorists or pedestrians at risk.

“The first thing I learned was that Lyft had its act together, even when users — or this user — did not.”

“One thing that’s interesting is whether your eyes are going to the right places. Are you finding everything you’re looking for?” Bartels said. “Another thing that we like to do is play this back for a research participant and have them talk us through what’s going through their mind. Were there things that were confusing or disorienting, or places where you got stuck?”

For me, that place was the credit card reader on the kiosk. The system allows you to process payment without the app, and I imagined that would be the easiest option. But after several failed attempts to get the machine to read my card’s magnetic strip, I abandoned the effort.

A message on the kiosk, prominently shown in a digital display near the card reader, notifies users that they can use the Lyft app as an alternative to renting the bike via the kiosk. Having never used Lyft to ride a bike — in fact, the app was uninstalled on my phone after a long, ride-share hiatus during the pandemic — the software let me unlock the bike after a straightforward, if somewhat lengthy, series of steps.

Here’s how the onboarding process went:

- I reinstalled the Lyft app. (A verification code was sent via email to authenticate my existing Lyft account.)

- Allowed Lyft access to geolocation data.

- Agreed to COVID-related health and safety guidelines.

- Viewed a Lyft map with bike icons signifying docking stations, and read several bike safety messages.

- Pressed a large purple button that said “Scan to unlock.”

- Scanned the QR code on the bike’s handlebars.

- Freed the bike from the dock after hearing a chime.

All told, it was a fairly seamless process. My eyes were focused on the key targets, rarely wandering to unintended visual territory, and the app’s organizational hierarchy and bright purple iconography led my gaze to high-priority information on Lyft’s map — a top-level search bar to type in destinations, bike icons to show docking stations, and indicators showing the number of available classic bikes and e-bikes at nearby stations and the cost of rides.

“We would say this was a pretty positive user experience,” Bartels said. “There’s the one issue with the card reader, which can’t necessarily be put on Divvy. But in terms of actually unlocking the bike, figuring out the mapping system, getting the app downloaded, all of those steps seem to be relatively straightforward.”

Something as Innocuous as a Gear Shift Can Be Tremendously Important to User Safety

Even for someone familiar with the neighborhood, there’s a lot to look at along Milwaukee Avenue, a major thoroughfare leading from Chicago to the northern suburbs. During the ride, I passed the neon displays of taquerias, bronze fermentation tanks in distillery windows, gyms, tattoo parlors, cars and pedestrians. But with the exception of a few times when my eyes wandered, landing, for instance, on a lovely wall-sized mural of Quincy Jones, they stayed mainly on the road.

Some of this may have had to do with my own self-awareness that visual data was being recorded. The frames are relatively inconspicuous — think actor Ben Stein’s dark-rimmed specs with a little extra mass near the arm hinges where the sensors live. They’re lightweight and completely transparent. For most of the ride, I forgot I had them on — most of the ride, but not all.

I became conscious I had the glasses on when I tried to switch from first to second gear. The numerals (from one to three) on the bike’s dial are oriented horizontally on the handlebars, whereas the actual shifting mechanism is oriented vertically. As I struggled — unsuccessfully — to shift gears with my thumb, the red dot in the recording showed my eyes straying from the road.

Eventually, I gave up, which was a good thing since moments later a minivan swerved across the bike lane into an open parking space — not exactly a near miss, but a close enough encounter to reorient my attention.

This is just the sort of usability issue the eye-tracking software is designed to flag, Bartels said.

“You would definitely want to flag the confusion on the gears. Because anything that takes attention away from the road, even for a couple of seconds, is potentially leading to you getting hurt or injuring a pedestrian.”

Tobii Pro Glasses 3 records lived experience much like a GoPro camera, he explained. A system of illuminators and miniature cameras track where your pupil is, and triangulate the direction of your gaze though space. The eye tracker lives in the hardware, and video and audio data is processed by an algorithm. When you play back the recording on the Glasses 3 app, a red dot reveals where your eyes have travelled — and, importantly, where they linger.

“For the most part, this experience showed that you were able to focus on the road and not get too distracted,” he said. “But you would definitely want to flag the confusion on the gears. Because anything that takes attention away from the road, even for a couple of seconds, is potentially leading to you getting hurt or injuring a pedestrian.”

We Look at a Lot of Ads, but We Don’t Remember Most of Them

One thing eye-tracking software makes abundantly clear is how much of the world is legible to the eye. I saw advertisements for colleges, discounted fruit, gym memberships and ketamine infusions; and that’s to say little of the semiotics — McDonald’s iconic Golden Arches and a faux statue of Lady Liberty on the awning of a bank, for instance. But in reviewing the tape, I realized most of what I saw I completely forgot.

“And that’s, of course, why eye tracking is used so much in advertising research,” Bartels said. “Because we look at thousands of ads and brand messages every day. Most of which we just don’t remember or process.”

But that doesn’t mean we don’t notice them.

“Most people say ‘advertising doesn't work on me or I don't look at the ads,’” he said. “But what we can see in the attention data is that you do.”

The deeper reality is people notice ads, but the ads fail to leave a lasting impression.

“Is it not visually engaging? Or is it not memorable? In the eye-tracking data we can pick apart which of those problems it is,” Bartels said.

“Most people say ‘advertising doesn’t work on me or I don’t look at the ads.’ But what we can see in the attention data is that you do.”

And sometimes eye-tracking studies can reveal unexpected ways in which ads flop.

Take, for instance, a study Tobii Pro conducted with a company developing packaging for frozen burritos. The company had their favorite design picked out — it was, to their minds, a beautiful photograph of a microwave burrito. But people weren’t buying it, and interviews with customers weren’t revealing why. So the company did an eye-tracking study. What they found was a high correlation between time spent looking at the burrito and the decision not to buy it. A giant, high-definition microwave burrito smothered in sauce, it turns out, is not particularly appetizing.

Here’s How Eye-tracking Is Used by UX Designers in Formal Experiments

But let’s get back to the cycling experiment. Because I was a lone user taking a single test ride, the attentional data collected were fairly limited. When UX teams use eye-tracking devices to run more formal user tests, Bartels said, they typically do so with at least 15 users, who represent a statistically meaningful sample.

Heat Maps

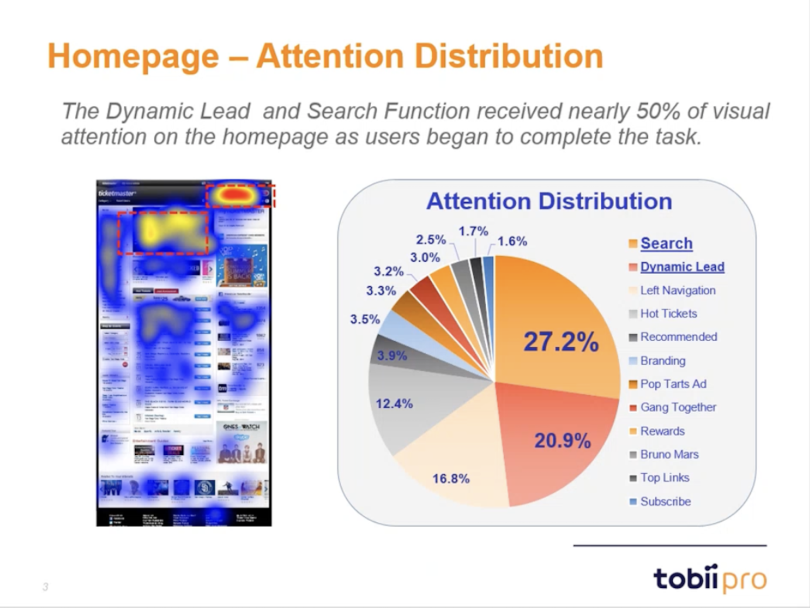

To illustrate, Bartels showed me a sample web browsing study conducted by a large ticketing company that wanted to understand what users viewed when attempting to purchase tickets to a John Legend concert. A heat map showing the percentage distribution of eye movement across the landing page — which areas of the page were getting noticed and which were getting ignored — revealed most of the focus centered on two key areas.

“So there’s this rotating carousel, dynamic lead at the top that has three or four events that are coming up, and then there’s the search box,” Bartels said. “And those are the big hotspots you see on the page. If you look at the actual numbers, you can see that about 50 percent of users’ time was spent on those two things.”

“That’s sort of the challenge for UX developers who are interested in engagement: getting people to see more things that are for sale — more events, more concerts, more advertising. Because the modern user doesn’t linger very long.”

Eye-tracking data on the heat map led the design team to two major insights, he told me. First, it suggested the “search first” mentality of modern internet users.

“‘Find tickets to a John Legend concert was front and center in the dynamic lead,” Bartels said. “But we had so many users that didn't see it there because they have this search-first mentality. You get to a website or you get on an app, and it’s immediately, ‘Where’s the search bar? Where’s that little magnifying glass icon?’ That’s sort of the challenge for UX developers who are interested in engagement: getting people to see more things that are for sale — more events, more concerts, more advertising. Because the modern user doesn’t linger very long.”

The second takeaway was that the hot areas of the website, those colored in red and orange, were also prime real estate to add key functionality and ads — in effect, capturing the bleed of users’ peripheral attention.

“So, for the UX designer, that means, if there are other things that need to be seen, can we put those in close enough proximity that it’s going to capture some of that attention?” Bartels said.

Visual Flow Maps

Another way eye-tracking data can be analyzed is in a visual flow map. This is a time-sequenced list showing how long it takes users to find features, offers or site functions.

“So what people tend to look at first, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, all the way down the line,” Bartels explained. “And if you’re trying to get people to notice ‘Hot Tickets,’ for example, you can see from the attention data that it’s the seventh thing users look at, and it’s not until they've been on the page for 15.3 seconds, which is an eternity in web time.”

Moving “Hot Tickets” closer to the top of the page is likely to draw more interest. It’s not necessarily that users don’t care about the offer, Bartels told me, it’s that they’re not seeing it.

These types of studies work best, he added, when design teams have a specific objective or research question in mind. Why aren’t people clicking on “Hot Tickets”? How can the design team boost engagement?

Usability Testing

Perhaps the most powerful use case for eye-tracking software is usability testing. In this same study, when web visitors were trying to find and buy seats to the John Legend concert, several ran into a problem at a critical stage. A map of the stadium showed open seats, which could be selected for purchase. But selecting a seat wasn’t the end of the task. Users also needed to click an inconspicuous blue button buried in the lower right-hand corner of the screen.

“You'll notice, when they click the seat, the ‘Buy Tickets’ button in the bottom right corner becomes active. But you can also see that the user doesn't notice that,” Bartels said.

“If you can show your design team a video like this that shows the agonizing visibility error, that’s gold.”

I didn’t either until Bartels pointed it out. Instead, I was focused on the red dot jumping frantically on the screen — a clear sign of the prospective buyer’s utter confusion.

“This is one of those lightbulb moments for a UX designer,” Bartels said, pointing out the jumping red dot. “You can tell somebody, ‘Oh, the button’s not being seen.’ But if you can show your design team a video like this that shows the agonizing visibility error, that’s gold.”

But is eye-tracking necessary to collect such data? Can’t similar studies be conducted using remote user testing services, such as UserTesting and AnswerLab, or web analytics plug-ins, like Hotjar and UserZoom?

“Those are excellent tools, and we would never argue that eye tracking is a replacement for that research,” Bartels acknowledged. “On the other hand, we argue that eye tracking is a way to augment that type of reasoning. You’re able to understand clicks, abandonment, and scrolling and all sorts of other factors through those platforms, but you aren't able to understand where the eyes are.”

Weaving the two together — and jogging users’ memories with recorded footage — presents a richer, qualitative picture of user behavior.

And, on a personal level, I can say the eye-tracking data did alter my perception of city biking. Next time I’m out on a Divvy, I’ll pay less attention to the gear assembly. Chicago is pretty flat, anyway.