Job networking is a chore, even for those with connections from a high-profile alma mater or plugged-in friends. The COVID-19 pandemic, with its social distancing and stay-at-home decrees, has only made an already difficult task even more so. In the engineering sector, where college degrees are no longer necessary to score well-paying gigs at major companies, who you know can help leverage what you know.

That’s where Andres Barreto comes in.

By the time the Colombia-born tech entrepreneur graduated from the University of Miami in 2009, he’d already learned many of the skills that would enable him to found several startups, including Cloudomatic, Onswipe and Grooveshark, and sell the first two. A political science major, Barreto had studied (per his LinkedIn resume) “the impact of social media technology on social and political movements.” His more technical knowledge, though, came from pouring over YouTube videos, Wikipedia blogs on programming and other informal sources. In other words, he learned the way many others in tech learn: on his own.

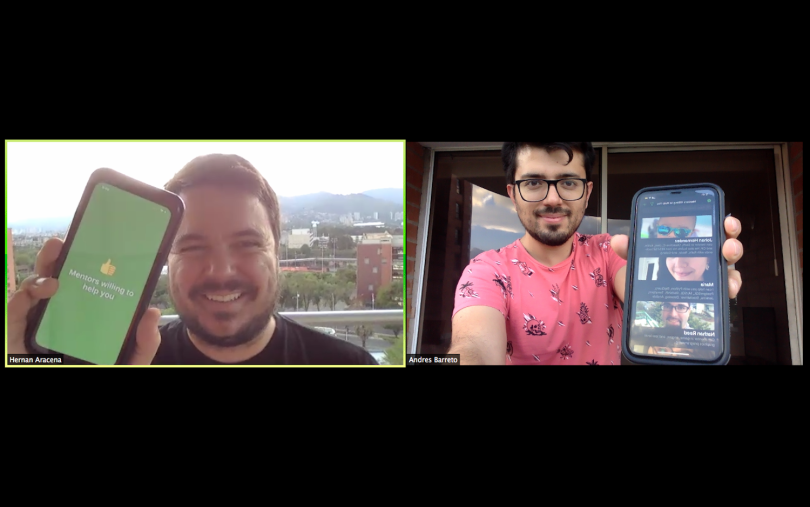

In 2012, Barreto founded the nonprofit educational organization Coderise, which teaches coding to kids (another arm focuses on software engineering for adults) in Latin America and at affiliated institutions in the United States and elsewhere. The next year, he linked up with software engineer Hernan Aracena to invest in Aracena’s San Francisco-based edtech platform Oja.la. Now the two have combined forces once again to launch a product they’re confident will fill a large gap in the tech marketplace: a free mentoring app for engineers through which junior programmers can seek guidance from experienced professionals. They think it will be especially useful for programmers who are self-taught or learned through boot camps — those who don’t have the benefit of a high-profile alumni network to lean on for support. One of their top goals, Baretta said, is to broaden tech’s infamously narrow demographic to include more women and people of color.

“Throughout this process of education in programming and entrepreneurship, I noticed that the No. 1 factor for success, once you have the skills, are your connections and who has been your mentor,” Barreta said.

“The reason we’re focusing on this vertical,” he added, “is because it’s the one that’s able to provide more upward social mobility, more income and more opportunity to more people in less time. With accounting or finance or even medical consulting, it’s really hard to get into McKinsey or JP Morgan if you don’t have a degree. But if you’re a great programmer, you can go work at Apple and Facebook and IBM. They’re no longer asking for degrees. The opportunity for that isn’t as big in other fields as it is in programming.”

In addition to mentors Barreta and Aracena know personally, their database is seeded with numerous others scraped from social media — specifically, from the Twitter feeds of those who’ve publicly expressed interest in helping out. And since many of these generous folks have their DMs open, that’s currently the primary path of contact. The mentees and mentors take it from there, deciding how they’ll communicate going forward. Before long, Barreta said, the mentorship pool will ideally become more organic.

Maria Gandicia, a data engineer at bearing.ai, decided to come on board as a mentor for personal reasons. “When I left my hometown in Venezuela, I had a great mentor in the U.S. — my ex-boss — who dedicated time and efforts to help me improve not only my programming skills, but also my soft skills,” she said in an email. “And that made a huge difference for my career. Becoming a mentor is a way to somehow give back in these difficult times.”

Initial users, about 500 of them, are being drawn from coding bootcamps in America and overseas that are affiliated with Barreta’s Coderise organization. But seeing as there are an estimated 23 million (soon to be nearly 28 million) software developers worldwide, Aracena noted, there’s plenty of room for expansion. To eliminate communication barriers, business will be conducted primarily in English. According to Barreta, there’s another reason for that: “A person who is confident with their English tends to make twice the amount of money as a person who isn’t. So we have to be careful in catering to other languages because it will have an impact on income potential.” And according to a demonstration from Aracena, users can search for a specific discipline or use a filtering function to see only mentors who are versed in Javascript or Python, among a variety of other programming languages.

In the months ahead, Barreta is confident a solid business model will emerge. Though this endeavor is partly about lending a hand, it’s also something that could eventually be monetized as a hub for software engineers who need assistance in preparing for tech interviews and negotiating contracts, among many other things.

Their ultimate goal, Aracena said, is to establish a robust talent accelerator for professionals along the lines of Techstars or Y Combinator, which cater to startups. For now, though, they’re keeping it simple — especially as the coronavirus pandemic rages and economic anxiety rises during what has fast become the worst job market in modern history.

“We strongly believe in what we’re doing,” Baretta said, “and that you have to give first to start creating value.”