For many startups, wading into the world of intellectual property can seem like a daunting task.

Not only are there significant financial considerations, there are different categories of IP to choose from. In the United States for example, there are three such categories – patent, trademark and copyright – each having subtypes of IP rights within those categories.

While a complete IP portfolio should include all different types of rights, obtaining a patent should be a top priority for any startup. In fact, many investors will insist on patent rights prior to investing.

In this article, I’ll explain why a design patent may be a good initial choice for startups and inventors working with a limited budget and on a tight timeline.

Design vs. Utility Patents

A patent is an essential investment for anyone looking to commercialize a product. At its core, a patent is a finite right of exclusion. Upon passing the tests for patentability, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) will grant an applicant a limited monopoly on their invention in exchange for the public disclosure of that invention. This means that during the term of the patent, 20 years from filing for a utility patent or 15 years from issuance for a design patent, the patent owner can prevent others from making, using, importing, selling or offering to sell the patented invention. Once the term expires, the invention is deemed to have been dedicated to the public so that anyone can use it.

In the U.S., we have two types of patents:

-

A utility patent protects the functional aspects of an invention: what something does, how something works, a chemical formula, etc.

-

A design patent, in contrast, protects the overall visual appearance of a design. Design patents claims are limited to ornamental features and cannot include functional elements.

There are two big factors why a startup or inventor should consider a design patent for their first venture in the world of IP: time and money. In short, the cost to obtain a design patent is typically a fraction of that required for a utility patent, and design patents will typically issue much faster than their utility patent counterparts.

The Time Advantage

Let’s first discuss timing. In the U.S., both utility and design patents are substantively examined. That means that once an applicant files a patent application, before receiving an issued patent, a USPTO examiner reviews the application and determines if it passes the tests for patentability: Is the invention new, novel, non-obvious, sufficiently described and enabled? This examination understandably takes some time, and therefore the USPTO has quite a backlog of pending applications waiting to be examined. Once an examiner reviews an application, they will issue a first office action. This will typically fall into one of two categories, a rejection or an allowance.

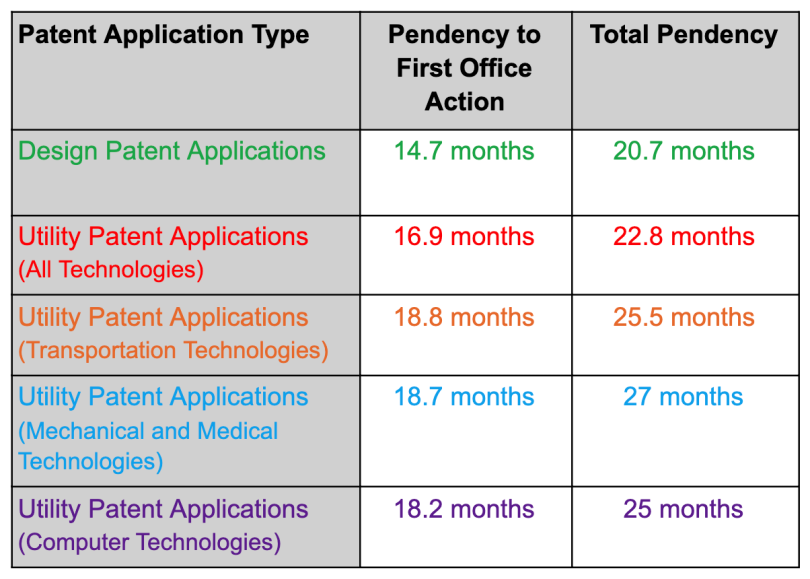

The USPTO provides a running tracker of the amount of time you are waiting to receive a decision for both design patents and utility patents. The USPTO tracks both pendency to first action and total pendency. The first-action pendency is the average number of months from the application filing date to the date a first office action is mailed by the USPTO. The total pendency is the average number of months from the filing date for a design to the date the application has reached final disposition (e.g. issued as a patent or abandoned). The numbers speak for themselves:

One important additional consideration is that many utility patents will at some point require something called a Request for Continued Examination (RCE). An RCE is essentially refiling the application after having hit some sort of roadblock during prosecution, typically in the form of a final rejection. When factoring in the additional time taken by RCEs, the total average pendency for all utility patents jumps up to 28.1 months.

As you can see, by the most conservative metric, design patents see a first office action about 20 percent faster than utility patents. And in my experience, it is not uncommon to receive a first action for design patents within a year from filing.

The Cost Savings

Now let’s move on to cost. When adding up attorneys fees, USPTO fees and search fees, the average cost to file a utility patent application can easily range between $12,000 and $19,000. By comparison, the cost to file a design patent application will typically be about a third of that, ranging between $2,000 and $5,000 depending on the complexity of the design.

Another important factor to consider are post-filing fees. These include, for example, attorneys fees for responding to an office action and issuance or maintenance fees. According to USPTO statistics, design patents have an objectively higher allowance rate than utility patents. U.S. design patents have an allowance rate of over 85 percent. In contrast, the average allowance rate for utility patents between the years 2006 and 2018 was 51.3 percent. Additionally, research shows design patents typically have a much higher first-action allowance rate – where they are allowed at the first instance without a rejection – of about 59 percent. First-action allowances for utility patents are exceptionally rare. It is far more common in practice for design patents to receive a first-action allowance than utility patents.

Putting all this together, not only is the initial cost of a design patent application a fraction of that for a utility patent, but because design patents have a higher allowance rate and especially first-allowance rate, the post-filing costs are also likely going to be considerably lower for a design patent. And if that doesn’t sound good enough, design patents, unlike utility patents, do not have USPTO maintenance fees due after the patent has been issued.

Design Patent Drawbacks

While design patents certainly have their benefits in terms of time and money, they do have some limitations. As mentioned, design patents protect the appearance of something, not the function.

Therefore, design patents will not protect against redesigns with the same underlying function but a very different appearance. That said, design patents can nonetheless be an effective initial means of IP protection including in takedowns of knock-off products on online marketplace like Amazon.

Design Patents Do the Trick

Design is integral for almost any consumer product. People want to buy products that look appealing. Design patents give you three different ways to protect the appearance of your product:

-

The physical form of product itself

-

Packaging for the product

-

Graphical user interface for software

So while a design patent cannot protect any underlying function, it can protect against a competitor copying the appearance of your product. The threat of patent litigation will make any would-be infringer think twice about copying your product design. Additionally, if a competitor does choose to enter the market, they cannot just make a simple copy; instead, they’ll need to spend resources to change the appearance of the competing product, which helps to differentiate your patented product.

All in all, design patents tend to be stronger as part of a combined portfolio with utility patents. But if you wish to have some initial IP protection and have the ability to place that coveted “patented” mark on your products, as an initial step when bringing a product to market, applying for a design patent may be a great option.

The opinions expressed here are the present opinions of the author and may not reflect the opinions of McAndrews, Held & Malloy, its clients, or any individual attorney or employee. This is for general information purposes and is not intended to be — and should not be taken as — legal advice.