If you don’t consider the Midwest a hotbed of tech innovation, you’re probably not a venture capitalist. Over the past decade, annual venture funding for startups in the “Mighty Middle” of the United States — essentially, the 25 non-coastal states — has more than tripled, according to a new report from Dundee Venture Capital and Crunchbase.

Back in 2010, startups in this central region attracted $5.8 billion in venture funding, By 2019, that number had swelled to $20.2 billion. In the fourth quarter of 2019 alone, VCs invested nearly the same amount in the Mighty Middle that they invested in all of 2010: $4.7 billion.

Then the coronavirus pandemic began. The economy ground to a halt. More than 20 million people lost their jobs.

Will the virus undo a decade of growth for Midwestern tech ecosystems?

In the first quarter of 2020, investment in the Mighty Middle certainly dropped, from $4.7 billion the previous quarter down to $2.5 billion. That’s a 47 percent quarter-over-quarter drop, and a 34 percent drop year-over-year, according to the report.

It’s not quite as bad as that sounds, though. Huge funding rounds, or “megarounds,” in previous quarters skew those percentages high. Take them out, and investment was only down about 19 percent year-over-year this past quarter, and only about 11 percent quarter-over-quarter.

New funding data could still come in, too, noted Gené Teare, head of research at Crunchbase.

“We’ll be well-served here during this downturn.”

The key takeaway is not so much that investment has slowed, Teare told Built In, but that it hasn’t stopped. Investors aren’t reacting the same way they did to the 2008 recession, when many took took a “wait and see” approach, putting investing on hold until the economy stabilized.

Today, “investors do see this as an opportunity to invest,” Teare said — though the coronavirus has certainly triggered a “reset” in terms of forecasts and VC strategy.

Greg Beaufait, a partner at Dundee Venture Capital, also remains optimistic about the Mighty Middle’s future. Unlike coastal unicorns, which often take a “growth-at-all-costs” approach, he said, companies in the Mighty Middle tend to focus more on “efficient growth” — in other words, stretching their funding, maintaining a cash reserve, and not straying too far from profitability.

Companies like this have more runway for weathering crises, including a global pandemic.

“We’ll be well-served here during this downturn,” Beaufait, who’s based in Minneapolis, told Built In.

The report calls the region “mighty” for a reason, it seems.

Rise of the Underdog

In the late ’90s, anyone in tech calling Midwestern states “mighty” would have been laughed out of the conference room. Founders in the Midwest were at a massive disadvantage. Even founders in Northern California had trouble attracting venture capital.

“VCs wouldn’t even go up to San Francisco,” Teare said, laughing. “That was seen to be outside of tech. Why would they travel so far for a board meeting?”

Times have changed, needless to say. Today, venture capitalists travel constantly, investing in companies in Europe, India, China and across the U.S.

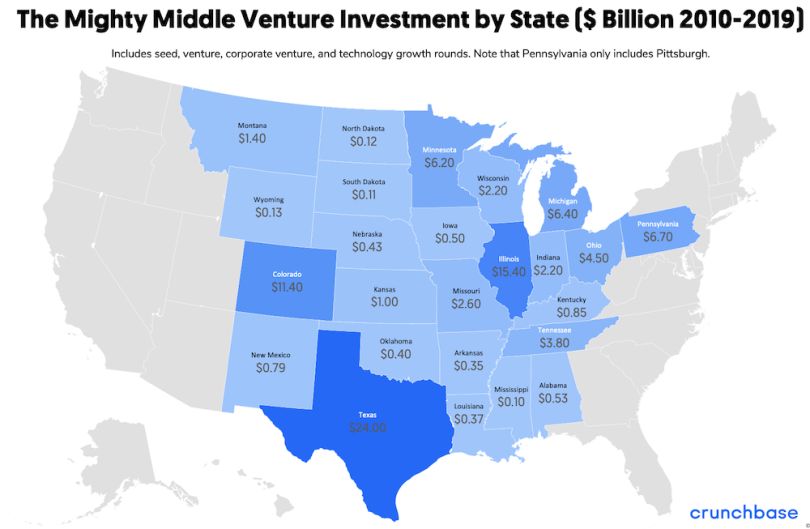

Their Mighty Middle investments have clustered in a few key tech hubs, according to the new report — specifically in Austin, Chicago and Denver. Each of those three metro areas saw more than $10 billion in VC seed investment over the past decade.

Those totals, often driven by massive later-stage funding rounds, don’t show the overall “health of the ecosystem” in a city, though, Beaufait said.

A better indicator of the health of a local tech scene: the level of seed funding. Though nationally, only about 10 percent of venture funding went to seed-stage companies in the 2010s, seed-stage investing constitutes about 70 percent of all venture deals. In other words, it’s a low-stakes, commonplace form of funding — and a gateway to the bigger leagues.

Austin, Denver and Chicago all saw over a billion dollars in seed-stage funding over the past decade. And in Austin and Denver, seed-stage funding represented about 11 percent of all the decade’s venture funding, which puts the ecosystems above the national average. Chicago, meanwhile, lags slightly in terms of proportions, with only 7 percent of its venture funding going to seed-stage companies.

It’s important to watch these seed funding metrics, though, Beaufait noted, because they’re signals of future prosperity.

“If there’s activity happening at seed today,” he said, “our hypothesis would be that there’s gonna be pretty serious growth happening at Series A, Series B and late stage and exit activity down the road.”

“Jumping in and leading at the seed stage is something the coastal investors are less likely to do.”

Seed funding also signals active, local VCs. The report, rooted in data supplied to Crunchbase by founders and venture capital firms, found that local investors led 71 percent of seed rounds in the Mighty Middle, while later-stage fundraising rounds were often led by coastal investors.

“Jumping in and leading at the seed stage is something the coastal investors are less likely to do” in the Mighty Middle, Teare explained. “The local scene is incredibly important as an introduction.”

Luckily, the Mighty Middle has local scenes now — plural.

It wasn’t always so diversified. The region’s rise began with Chicago success stories, Beaufait said, specifically Groupon and Grubhub. Both behemoths made it to IPO in the early 2010s, and in presentations to investors, Beaufait often pointed to them as proof of the Mighty Middle’s potential. It helped that both were consumer-facing companies, he said. “It’s easier sometimes to grow the consumer-facing companies that grab the headlines than the enterprise companies that are a little more behind the scenes.”

Those early Chicago successes kickstarted the “flywheel of more capital flowing into this region” for the whole region’s tech scene, according to Beaufait.

Seed-stage venture funds could point to them to raise capital, and then they could fund new, successful startups, which they could then point to to raise even more capital.

Though the novel coronavirus has put a short-term pause on this growth trajectory, Beaufait doesn’t see the pandemic causing long-term damage to the Mighty Middle’s tech ecosystem. The region has everything it needs: proven success stories, research institutions and plentiful engineering talent, much of it from Big Ten schools.

“It’s ... an easier pitching atmosphere for us than it was 10 years ago,” he said.

So Who’s Mightier: The Mighty Middle or the Bay?

Could the Mighty Middle’s startup scene overtake the Bay Area’s? In terms of attracting venture capital, it hasn’t come close yet. In 2019, Bay Area startups attracted roughly $46 billion in venture capital, more than twice the amount raised that year by the entire Mighty Middle combined.

That doesn’t tell the whole story, though. While 2019 was an all-time high for investment in the Mighty Middle, for the Bay Area, the year actually represented a major dip from the amount of venture capital raised in 2018: a record-setting $63.6 billion.

Anecdotally, too, it seems that the Bay Area may have peaked as a hotspot for tech talent. Plenty of tech professionals move to the Bay while they’re young, to hone their talents, Teare said; San Francisco is getting younger, and less than half its residents are over 45. But for an American city, San Francisco has a record-low proportion of children. When they want to start families, residents tend to flee the area’s sky-high rents.

Some of them flee to the Mighty Middle.

Why? Well, not only does the Mighty Middle have a profusion of interesting tech companies, Beaufait said, it also has some strengths Silicon Valley lacks. While Silicon Valley has a long history of technological innovation, the Mighty Middle hosts plenty of non-technical Fortune 500 companies’ headquarters. The whole region is a major center for healthcare; Chicago has historically been a logistics hub; Detroit, meanwhile, was famously the center of the automotive industry.

These links to old-school industry have become an asset. The line between tech companies and other companies has blurred; every company needs technology in some capacity. Tech companies in the Mighty Middle can invent essential products for the enterprises in their cities.

In fact, they already do. The region’s unicorns often serve their home states’ legacy industries. Bright Health, a health insurance startup valued at more than $1 billion, is based in Minneapolis, a stone’s throw from the Mayo Clinic. Meanwhile RigUp, an Austin-based startup valued at $1.9 billion in 2019, offers digital workforce tools for energy companies, including Texas’ famous oil companies.

The Mighty Middle has other advantages too. Startups in the region often have better luck recruiting than those in the Bay Area — even though Silicon Valley attracts more venture investment and hordes of engineers.

“To be honest, there’s not enough talent [in the Bay Area] to meet the demand.”

“There’s incredible competition here for engineering talent,” said Teare, who’s based in Palo Alto. “To be honest, there’s not enough talent to meet the demand.”

Not so in the Mighty Middle.

But the region faces its own challenges. While it has plenty of homegrown engineering talent, it’s thinner on experienced tech sector managers and leadership, Teare noted. Seasoned professionals leaving Silicon Valley, though, can help fill this gap.

Like the rest of the nation, the Mighty Middle tech scene is also less than hospitable to women founders. All-women founder teams amass about 3 percent of venture capital in the Mighty Middle and across the country. Co-ed founder teams don’t fare much better, raising 7 percent of capital in the Mighty Middle and about 10 percent nationwide.

“We’re so far from parity,” Teare said.

She sees signs of hope, though. The proportion of venture funding going to co-ed founder teams is on the rise, “albeit slowly,” Teare said. She’s also been impressed by an organization called All Raise, which helps connect women VCs with women founders for networking and mentorship.

Ultimately, she and Beaufait would both advise a founder in the Mighty Middle to stay there, rather than move to the Bay Area. The capital is already “in your backyard” in the Midwest, Beaufait said, and it’s easier to access VCs there than in the Bay.

Furthermore, the Mighty Middle’s startup scenes are on the rise, while the Bay Area’s future is murkier. Beaufait foresees growing venture investment in the Mighty Middle for the next decade.

“We see investments going up, but they certainly haven’t peaked,” Teare concurred. “I still think we’re in the early stages of this.”