Jake Heller was fed up with being a lawyer. Not practicing law itself — that part he loved. Rather, he’d become endlessly frustrated with how much time it took to prepare for every case, even with the help of technology. “Being a lawyer in 2020 feels a lot like being a lawyer in 1920,” Heller said. The problem, he added, is that no tech platform had tried to make a lawyer’s job more efficient even in the digital age.

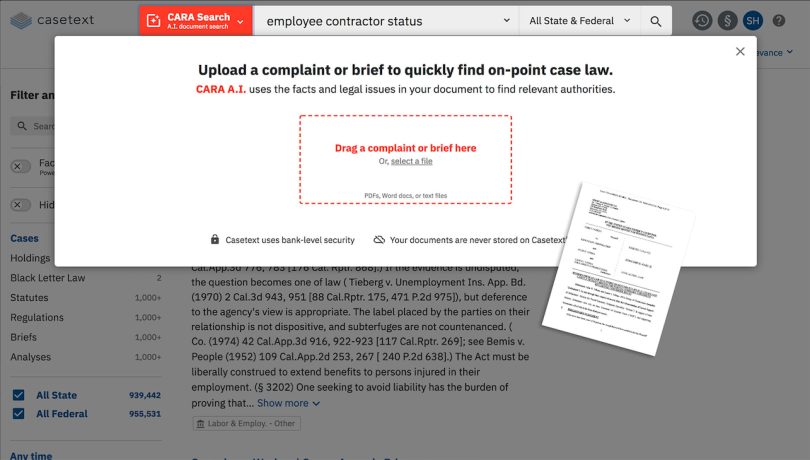

So, Heller decided to fix the problem himself. In 2013, he launched Casetext, an AI tool for lawyers. Some litigators spend about 50 percent of their time researching, drafting and filing motions, and the process can take months. Casetext’s AI tool, named CARA, finds the same facts, legal resources and jurisdiction matters as the case a lawyer is researching, significantly reducing the amount of prep time for a case. The tool is used by nearly 5,000 small law firms throughout the country.

The standard legal tech platforms, LexisNexis and Westlaw, have both been around since the 1970s. These databases made their way online with the advent of the internet, but little has changed since then, Heller said. Before the legal tech sector started taking off within the past 10 years, “everything was done more expensively and less efficiently,” Heller said. “There was less of an eye on consistent quality and the people who need legal representation.”

State studies show that up to 80 percent of people who need legal help in the U.S. can’t get a lawyer. Casetext wants to modernize the legal sector by making a lawyer’s job more efficient so they can help more clients. The platform also provides access to a sort of virtual lawyer for people who don’t have representation. The AI tool is already used by inmates in prisons across the U.S. who are appealing their cases.

But don’t fear the robo-lawyers just yet. “The lawyer will always do the more human tasks,” Heller said. “Robots can’t persuade and they can’t make arguments, so it’s impossible to take out the human element of being a lawyer,” he added.

How A Lawyer Built an AI Tool

Before launching Casetext, Heller had a nuanced legal career, working for the Obama administration and the first circuit court of appeals. He also served as president of the Stanford Law Review.

Although most of his jobs have been in law, Heller has roots in tech. He grew up in Sunnyvale, California, a stone’s throw from where Apple, Google and Facebook sit today. And in true Silicon Valley style, Heller’s dad started an internet business out of the family garage in the ‘90s, which had a big influence on him. “I’ve been building and coding since I was eight or nine years old,” Heller said. “Later, I developed a passion for law and policy which led me to law school, but I missed building things.”

Heller ruminated on the idea for Casetext for about six years before it launched, but he always assumed someone else would be the one to make it a reality. “Finally, my wife said, ‘either stop talking about it or do it,’” Heller said. “I applied to Y Combinator and the rest is history.”

But there were actually quite a few steps in between.

In designing the Casetext platform, Heller’s ultimate goal was to minimize the hefty research a lawyer has to do before a trial.

At a very high-level, a critical part of a lawyer’s job is gathering precedents, which are court decisions in prior cases with similar facts as the case currently before the court. Judges will typically use the precedent to inform their decision in the current case unless one side can prove that it was wrongly decided.

The premise is, “what the previous law decided is likely to be true again,” Heller said. “But finding a precedent is an extremely arduous task.”

That’s where Casetext comes in. Lawyers using Casetext can drag and drop core documents from the current case they’re working on. Then, CARA, the AI platform, reads and interprets those documents and uses them to find accurate precedents from prior cases. “It goes over one billion pages of text and lands on the right one,” said Heller. The search engine supports both boolean and natural language.

In addition to the search tool, Casetext also has a database of briefs written by attorneys all over the country that can help lawyers evaluate a case or statute.

A Robot for Lawyers

Karen Amlong is president of The Amlong Firm in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where she specializes in employment litigation. Last year, she took on a marriage discrimination case from a local fire department. In that case, firefighters who were married were receiving more money in their pension than those who were single.

“This was an unusual case for me so I had to learn about [pension law],” Amlong said. She decided to try out Casetext. “The first search I did, I got an answer right away and I’ve been using it ever since,” she said.

The law is frequently evolving, which is a constant challenge for lawyers. Amlong points to the Daubert Case, a 1993 Supreme Court decision that determined the standard for including expert testimony in a federal trial. Whether it’s a scientific expert or sociology expert, Amlong said, they have to go through an analysis to see if they meet the criteria. “Casetext allows you to go through that analysis easily,” she said.

Amlong added that she thinks Casetext has decreased the amount of time she spends researching each case by nearly 25 percent.

Making Legal Help Accessible to Everyone

Most inmates rely on public defenders to appeal their case or they choose to represent themselves in court. This presents clear challenges to someone totally unfamiliar with the legal process. But inmates have a constitutional right to a law library. Under this rule, some prisons have white-listed the Casetext website for inmates to research their own cases. The internet is often a better resource for inmates than a library with physical legal texts, as it can be difficult to keep up with frequent changes to the law.

Heller is glad his tool is a valuable resource for inmates trying to clear their name, but he still sees Casetext as a way to make actual lawyers more readily available. “Ultimately, most legal problems require lawyers, and will for the foreseeable future,” Heller said. “Expanding access to justice will mostly be about empowering attorneys to do more for clients who can only pay less.”

Changing The Future of Law

In the near future, Casetext will go beyond information gathering to give lawyers recommendations on actions. The platform will be able to recommend the best arguments a lawyer can make and give advice on writing legal briefs.

“Gathering information and ensuring you’re making the best argument can take months,” Heller said. “If we can make this process take 30 minutes, it changes the legal practice entirely.”