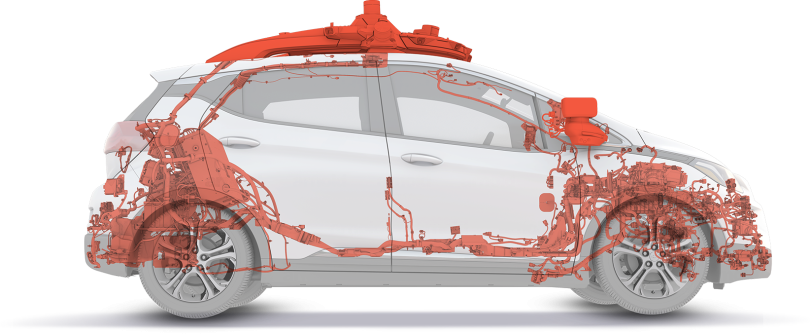

On the surface, the concept of a self-driving car seems deceptively simple. But after a decade of splashy announcements and enormous investments from Silicon Valley’s most influential organizations, few people understand the dichotomy between the idea and its execution better than Mohamed Elshenawy. As senior vice president of engineering teams at autonomous vehicle company Cruise, he spends his working life neck-deep in the challenges that come from building a self-driving car.

“One of the common questions I get asked by friends and family is, ‘Why does it take so long to solve the self-driving problem?’”

The answer?

“We aren’t teaching a human brain, which has already evolved over hundreds of thousands of years to accurately perceive the world and predict actions within their surroundings. We are essentially building an AV brain that can do all that without stagnating or making silly mistakes or getting tired, bored or distracted. In order to do that, we’re compressing hundreds of thousands of years of human intelligence into just a few years.”

Cruise Background

While some self-driving contenders have opted to test their technology on quieter roads in the hopes of solving “easier” driving conditions before venturing into complex urban driving, Cruise has jumped straight into the deep end — in this case, the hilly streets of its hometown. The theory goes that once you’ve solved city driving — with its construction sites, pedestrians, cyclists and haphazard traffic — it will be easier to scale out and expand the service elsewhere.

To support its engineering work, Cruise has organized its teams around the concept of psychological safety.

“We have to be willing to embrace risks within our safety bounds, different perspectives and new ways of doing things,” Elshenawy explained. “This experimentation mindset is part of a new paradigm shift we’re seeing toward ML-native companies, ones that are not just optimized by ML but defined by it.”

To learn more about the organizational architecture that provides space for innovation within its strict safety standards, Built In asked Elshenawy to explain what psychological safety means in practice.

Why is psychological safety especially important for an autonomous vehicle company like Cruise?

We are trying to do something that’s never been done before, and that inherently means this is an applied experiment in many ways. Psychological safety allows us to rewrite how we think about failure and makes room for innovation and individual growth — something that is core to Cruise’s value proposition — allowing people to unlock their full potential, speak up, raise flags without fear, effectively experiment, take on calculated risks and, ultimately, improve.

Taking a calculated risk that doesn’t pan out or having to pivot a project because it’s not yielding the results you were looking for is not a failure; it’s an opportunity to learn. The reality is we should have more “failed” experiments than successful ones, and my leadership team and I are committed to providing the psychologically safe environment and feedback mechanisms necessary to learn fast and fail forward, emerging from each experiment with valuable lessons that lead us to our next big win. As we continue to grow, I hope this culture of experimentation and innovation helps us maintain a startup spirit.

How does your organizational structure reflect and reinforce Cruise’s emphasis on psychological safety?

The organization is based on principles of continuous improvement, autonomy, simplicity and respect in order to facilitate growth, development and innovation for every individual and the team as a whole. My ultimate goal is to foster an innovation and learning mindset within my team, based on an organizational structure that is nimble enough to support effective experimentation yet disciplined in mapping against our goals.

Psychological safety is at the root of this. Every member of our team needs to feel empowered to experiment, speak up, ask for help or feedback and make bold moves within our safety guidelines. Vertical integration of teams and tools across the organization form functional units within groups that make iteration and quick innovation more seamless. We’ve also been deliberate in keeping the organization flat in order to allow information and decisions to travel faster in both directions, including why certain decisions were made in the first place. Not only does this give us the agility and speed to achieve our mission, but it also creates a respectful and inclusive culture. A great example of this is our quarterly planning and review sessions, which are open to all team members as well as shared externally to the company in order to ensure alignment, make sure voices are heard and provide folks with an opportunity to influence how we, as a team, operate.

What’s an example of psychological safety in action?

Beyond fostering a more productive working environment, psychological safety also quite literally translates into our on-road safety and performance. At the foundation of our iterative release process are mechanisms for feedback and reporting, reviewing and addressing risks at every level.

A common thread for safety failures in any company is that knowledge of the safety problem existed, but it wasn’t adequately communicated to the right people, with the right detail or action plan. We have designed a system, within our release cycle and across the company as a whole, that seeks to ensure there are no gaps in our identification and communication of safety risks, and that all identified risks are addressed at the right level with input from those with the greatest understanding of the specific issues.

The goal is to empower every person with knowledge of a safety risk to raise it effectively, to triage those risks efficiently and to address them promptly at the right level with the best possible information.

“It’s easy to view those safety parameters and requirements as limiting factors, but I’ve found the opposite to be true. It has pushed us to be more creative and rethink the conventional development process.”

Most companies would claim that they encourage ambitious projects and innovation. What sets Cruise apart in this regard?

AV is not a science project relegated to a lab — it’s real and it’s interacting with people and other drivers on the streets every day. This sets the performance and safety bar incredibly high and it’s something we take very seriously.

We have to balance cutting-edge innovation without ever compromising safety. It’s easy to view those safety parameters and requirements as limiting factors, but I’ve found the opposite to be true. It has pushed us to be more creative and rethink the conventional development process.

We have also invested heavily in end-to-end tooling that integrates to form an AI and robotics platform which is key to increasing our iteration speed. This includes homegrown tools such as Webviz, our open-sourced platform for robotics data visualization, and our continuous learning machine, a framework for self-supervised auto-labeling data and active learning data mining. These tools, paired with a unique CI/CD process, feedback loops that connect our simulation with real-world performance, and our powerful, scalable infrastructure, allow our engineers to understand their impact on on-road performance. At the same time, they can safely go from ideation to production in days.