When it comes to fixing our oftentimes broken online experiences, Ethan Zuckerman recommends looking backward more than a century.

Zuckerman, who heads the Institute for Digital Public Infrastructure at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst, kicked off his talk at last week’s New Public Festival with a brief history of radio. By 1922, the Soviet Union, United States and Great Britain had each taken divergent approaches to the fledgling technology. The Soviets used it to broadcast propaganda, while the U.S. system began to settle into an advertising-based commercial model. The United Kingdom, meanwhile, charted a third path: a civic-minded media built upon the public interest, “independent both of the government that was in power and of the commercial sphere,” Zuckerman told the audience.

The parallel was clear, but worth driving home.

“When a new technology comes to town, we have choices about how to use it,” he said. “It doesn’t necessarily need to broadcast propaganda, [and] it doesn’t have to become a commercial free-for-all. Instead, we can look at a new technology and invent something new.”

For Zuckerman, “something new” is what he calls “digital public infrastructure.” In short, that means using some manner of public funding to promote digital experiences that promote the public good. In practice, Zuckerman’s vision is multifaceted and, despite its already-clear ambition, still in the formative stages. So perhaps it’s easiest to explain what it’s not.

Despite the public-funding aspect and the broadcast analogy, Zuckerman’s vision is not “the PBS of Facebook,” he told Built In last week following the festival.

In fact, it’s not even just about social media.

“It’s not building one big thing,” he said. “It’s actually building a whole bunch of little things.”

What Is Digital Public Infrastructure?

Zuckerman laid out his vision for digital public infrastructure a year ago and expanded on his ideas last November.

One of the central points is the need for a more expansive digital-social ecosystem — “a wave of alternative social media platforms designed to meet the needs of local geographic communities and communities of interest,” as he described it last year. The hope is that thousands of individuals might one day start up small social-media networks, with space for public social sites as well, like town government platforms.

Another key component would be an aggregator, so instead of hopping from one platform to another, the user could cycle through within a single interface — like an RSS feed for social. It also calls for non-advertising-based search engines and a systemic study of the effects of digital media, to separate unfounded pearl clutching from genuinely problematic user experiences.

“The metaphors that we use are really important. Research has shown that when people imagine crime, for example, as a wild beast, they endorse different policies than when they see it as a disease.”

How to pay for such grand ambitions? Zuckerman proposes, in the long run, a 1 percent tax on “highly surveillant advertising,” which he calculates would net between $1 billion and $2 billion each year. That creates a pool for which individuals and organizations could apply.

“So you’re not creating PBS. What you’re probably creating is something like a corporation for public broadcasting,” Zuckerman said. “Only in this case, it’s taxpayer funded — those taxpayers are the platforms rather than individuals — and it becomes a grant-making mechanism that supports the experimentation.”

It’s worth pausing to recognize how monumentally ambitious all this is. There are serious cans of worms related to interoperability, content moderation and API accessibility, among other hurdles, even among the large platforms.

But the biggest challenge might be our national character itself.

Advocates for digital public spaces are fond of invoking parks and libraries as metaphors — publicly funded spaces that contribute to the common good, beloved by all. But in the U.S., new taxes and public funding allocation doesn’t exactly waltz into legislation, no matter how useful its aims.

Zuckerman is clearly accustomed to such skepticism, and he anticipated and addressed mine before I could even make it explicit.

“I do live in the United States in 2021, [so] I do understand that that’s a hard thing to pull off,” he said.

It’s “way too early” to initiate conversations with lawmakers, he added, but not so for feasibility research. In a nice dovetail with his radio metaphor, Zuckerman is starting by looking for traction across the pond.

“Europe and countries with a strong public-media tradition probably have a better chance of success than getting it off the ground across the U.S. at the federal level,” he said.

Second, he’s engaging the philanthropic community here in the States, so that when a proof of concept is ready, it’ll be greeted with sufficient interest — both general and financial.

“I am in no way opposed to social networks making money. ... My big point is that this is too important just to leave it up to the market,” he added.

What’s Possible Near-Term?

With the understanding that digital public infrastructure as a whole is a massive lift, is there anything within the framework that we might be able to pick up with relative ease?

As Zuckerman sees it, decentralized platforms are likely key to the fleet of social-media options he envisions, and the maturation of those technologies may be inching closer to primetime.

One notable example is Planetary, a peer-to-peer social network developed by ex-Twitter original employee Evan “Rabble” Henshaw-Plath, who announced the app’s iOS availability at the New Public Festival. Another is Twitter’s Bluesky initiative, the company’s still-under-construction planned foray into decentralized social media. (Presumably, no final approach has been decided, but at least one proposal centers on the specifics of how users interact with message threads. Also, Bluesky this week published a review of the decentralized ecosystem.)

“My worst nightmare in some ways is that we deplatform all the Nazis, and they essentially invent the distributed future, because they’re the only ones who need it. And that would suck.”

Of course, decentralized social media is nothing new. The federated system Mastodon arrived in 2016 on a wave of next-big-thing buzz. That hype wave has crested, but it’s become notable as a landing pad for communities that were deplatformed elsewhere, including, as Zuckerman mentioned, a sex workers network that was banished from Instagram and Twitter post-SESTA/FOSTA.

“Now we probably need people moving to these platforms not because they have nowhere else to go, but because they want to try different norms and affordances,” he said.

That said, there’s also the hate problem. Extremists are increasingly migrating to alternative social-media options after the crackdown following the Capitol riots. In the decentralized space, the most notable example is Gab’s migration to a fork of Mastodon, which predated the Capitol storming. Peer-to-peer advocates are also grappling with the queasy reality: The end-to-end encrypted messaging capabilities of p2p platforms pose a particularly daunting challenge in terms of moderation.

But as Zuckerman sees it, the bigots need to be beaten to the punch.

“My worst nightmare in some ways is that we deplatform all the Nazis, and they essentially invent the distributed future, because they’re the only ones who need it,” he said. “And that would suck.”

All of this probably sounds extra hairy within the context of even tangential public dollars. And to be clear, Zuckerman isn’t necessarily calling for public funding of Mastodon social networks, but noting the value of interoperable federated protocols. Either way, it’s time to see what ambitious ideas might actually stick.

“In some ways I’m doing this not because I’m convinced that I have the right solution, but because I’m convinced I probably don’t,” he said. “I have, I think, a plausible way of going out and doing it. But I don’t feel like I have the entire equation, particularly as it comes down to how could communities best use these tools.”

Models for the Future

It was in that spitballing spirit that the New Public Festival, hosted by Civic Signals, gathered last week to consider various visions and challenges of public-friendly digital platforms — although Civic co-founders Talia Stroud and Eli Pariser prefer the term “digital public spaces.”

“The metaphors that we use are really important,” Pariser said during the event. “Research has shown that when people imagine crime, for example, as a wild beast, they endorse different policies than when they see it as a disease.”

The thread extends beyond messaging, though, into design frameworks. Physical public spaces, Stroud and Pariser noted, are built for the public as a whole, rather than optimized for individual users. They are often designed with community input and tend to reincorporate successful design motifs that had unintended positive effects, such as curb cuts — designed for wheelchair users, but helpful for people pushing strollers or carts.

Manifesting that vision means knowing what works and what doesn’t. During the festival, Pariser and Stroud unveiled extensive new research into what qualities platform users prize most and how well specific platforms perform relative to those qualities. (Zuckerman was one of two dozen that served on an advisory board to Civic Signals during the research.)

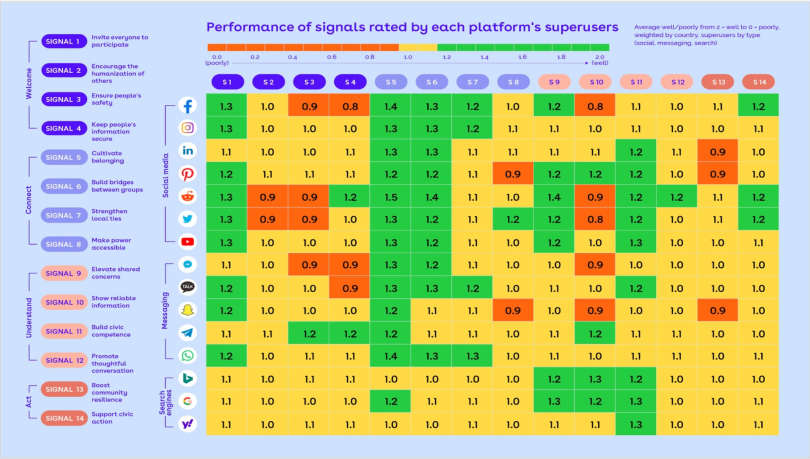

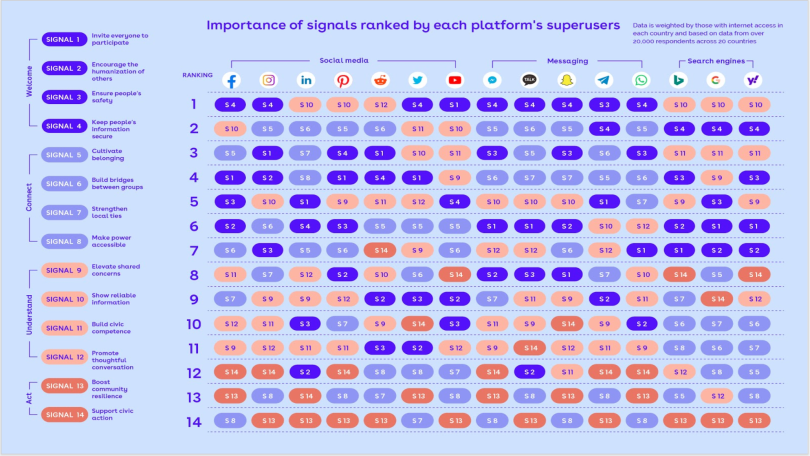

Pariser and Stroud collaborated with experts to come up with 14 qualities that users might value in digital platforms, ranging from “invite everyone to participate” to “support civic action.” They then surveyed 20,000 power users across 20 different countries to gauge the performance of 15 major platforms — including social media sites, messaging apps and search engines — along those qualities.

The scale ranks from 0.0, where all respondents said the platform performed poorly on a given quality, to 2.0, where all said it performed well.

Some interesting highlights emerged. Reddit scored the highest on any quality — a 1.5 on “cultivating belonging.” The lowest performance scores went to Facebook, for “keep people’s information secure” and “share reliable information,” despite the fact that those Facebook power users also ranked those two qualities as most important.

Zuckerman differs a bit from Stroud and Pariser in his approach to public-forward digital spaces, including in his belief that too much emphasis is placed on the problems of existing platforms over imagining new possibilities. But they all agree — and the research above bears out — that no single option will suffice.

Users will need a brigade of options — “localized, community-specific, public-serving institutions that can serve the functions in digital space that community institutions have served for centuries in physical places,” as Pariser wrote in Politico.

One model that Pariser has pointed to is Vermont’s Front Porch Forum, a 20-year-old local forum/digital newsletter that has become an unlikely model for online communities.

A daily “issue” includes some 10 posts from neighbors — and sometimes local businesses and officials — announcing everything from lost-pet notices to protests. The platform has a few key differentiators, Forum co-founder and CEO Michael Wood-Lewis said at the festival: no anonymity, every post is reviewed by a staff of community managers before publication, and the platform isn’t juiced to perpetually command attention.

“Our whole intent is that our members will spend five or 10 minutes a day on our service, not hours and hours,” he said. “And that will inspire them to have engagement in the real world.”

That raises a question: How transferable is such a model? How central is Front Porch Forum’s Vermont-ness to its success? The question itself is kind of the point.

Wood-Lewis recalled how each of the platform’s modest expansions, from Burlington to greater Burlington to rural areas beyond, was met with skepticism. Skepticism that was eventually overcome.

“That said, other folks will come to us and say, ‘We have to spread this everywhere,’” Wood-Lewis said. “And I said, ‘I don’t know how to design Front Porch Forum in the suburbs of Phoenix or in Miami.’ It needs local knowledge and local leadership to tailor it to local needs.”