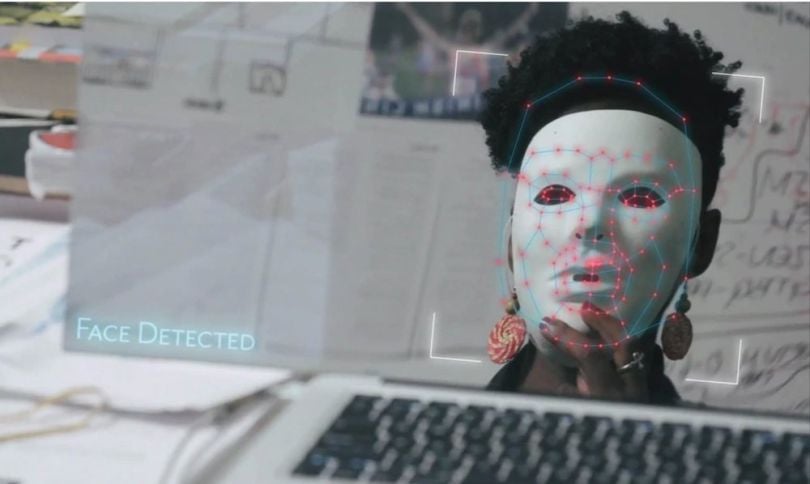

Coded Bias, a documentary about racial bias in facial recognition software, kicked off its debut (virtual) run in the United States on June 11 as part of the Human Rights Film Festival — just as the nation was in the midst of widespread protests demanding racial justice.

The run included a Q&A teleconference panel, which welcomed MIT Media Lab’s Joy Buolamwini, whose groundbreaking research illustrated how most facial recognition systems misidentify women and people of color and is documented in the film. The talk took place immediately on the heels of successive announcements from IBM, Amazon and Microsoft that they were — to varying degrees — stepping back from selling or distributing facial recognition software to police departments.

Festival programmers could have never anticipated such a seamless dovetail, but the timeliness of both the premiere run and the panel discussion was made possible by years of relentless research and advocacy — even in the face of attempts to discredit the findings.

Along with Buolamwini, the panel discussion included Deborah Raji, a fellow at New York University’s AI Now Institute who also works with Buolamwini at the Algorithmic Justice League; Safiya Noble, author of Algorithms of Oppression; Shalini Kantayya, director of Coded Bias; and Lee Rowland, a senior staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union’s Speech, Privacy and Technology Project.

The hour-long conversation is available to stream here via HRWFF’s Facebook page, but below are a few key takeaways from the discussion.

Some Organizations Call for a Full Moratorium on Facial Recognition Tech

The widespread protests following George Floyd’s death at the hands of police ultimately gave way to “the tardy corporate response that Black lives do matter” from tech companies, said Buolamwini. In her view, it was a genuine win that deserves to be celebrated, but more work lies ahead, including a federal pause on facial recognition software.

“It should not be that the face is the final frontier of privacy, but because we’re not just talking about police using facial recognition, we’re also calling for a federal moratorium on government use of all kinds of facial recognition technology,” she said. “So whether you have systems that are trying to guess your gender, race or your age, or you have companies like HireVue that will take your nonverbal cues from a video and use that to inform a hiring decision using facial analysis — this is not OK.”

The Algorithmic Justice League was one of more than 35 organizations that sent a letter in January urging an oversight board “to recommend to the president and the secretary of homeland security the suspension of facial recognition systems, pending further review.”

The letter cites a recent NIST study that found a 100 times greater likelihood of false positives in identifying Black people’s faces compared to those of white people in facial recognition technology. The highest rate of false positives is for Black women — results that are compatible with Buolamwini’s own research.

“[E]ven small error rates can result in large numbers of people mistakenly flagged and targeted for arrest,” Buolamwini wrote earlier this month in OneZero. “Since many of these systems have demonstrated racial bias with lower performance on darker skin, the burden of these harms will once again fall disproportionately on Black people, further compounding the problem of racist policing practices and a deeply flawed and harmful criminal justice system.”

Noble stressed that responsible tech regulation also needs to be paired with broader equitable policy. “You cannot regulate [tech] companies and then simultaneously defund every democratic counterweight,” she said, emphasizing the need to better fund public education, media and healthcare.

Regulating the Industry With an ‘FDA of Algorithms’

Buolamwini co-authored a paper alongside three other leading AI and computer vision researchers that argued for the establishment of a Food and Drug Administration-inspired federal authority for managing facial-recognition tech. The paper, released late last month, envisions a body that would classify and control the technology based on risk value, similar to how the FDA regulates medical devices and pharmaceutical drugs. (Read the non-technical “primer” of the white paper here.)

“If humans are in the picture, there will be some kind of bias, but how do we move toward something more like algorithmic hygiene?”

“The big takeaway from the FDA model is having evidence that backs your claims for what technologies can do, having red lines and guidelines that are based on risk, so that it’s not the case that anything can be released without having some kind of check,” Buolamwini said. The authority also needs to have in place “mechanisms to report and document the harms in the first place, so that you can go back and say what corrective action can be taken.”

Buolamwini argues that three key components, presently lacking at the federal level, need to be in place: affirmative consent, or not deploying the tech on people who have not agreed to it; meaningful transparency, or being clear and open about how, exactly the technology works; and continuous oversight.

“If humans are in the picture, there will be some kind of bias, but how do we move toward something more like algorithmic hygiene?” she asked.

Those components need to extend beyond legislative realms down to business, research and education, she said.

“At Georgia Tech, I was at one of very few, and maybe the only institution at that time, that even had an ethics course required for computer science,” she recalled. “And this is the ethics course you take when Senioritis has set in, in the spring ... [but] it has to be foundational,” she said.

At the same time, Noble stressed “a variety of different kinds of interventions,” including going beyond the business-level transparency paradigm and centering civil rights. “The tech evangelists are now reformed tech ethicists, and I think we need to be deeply suspicious of that and call that for what it is,” she said.

Indeed, Big Tech’s early track record on AI ethics is decidedly mixed.

Document, Document, Document

It’s an eternally relevant question for developers of conscience: How can working AI engineers make sure they’re building products that support algorithmic fairness and ethical standards — especially in environments where the two are not prioritized?

This often comes back to questions of culture, so it’s important to support efforts to organize, as Buolamwini pointed out. But in terms of day-to-day practical work, taking thorough notes is a small step that can have major consequences — the more thoroughly that engineering decisions and data set choices are documented, the greater chance of accountability, Raji notes. “There’s a lot you can advocate for as ‘part of your responsibility as an engineer,’” she said.

“Even at very big companies, you’d be surprised at how little all of that decision-making is recorded and how little we understand about data providence when we develop these tools,” she added.

Raji and Buolamwini’s work in Gender Shades revealed that the computer vision community had accepted a benchmark that was fundamentally flawed — which underscored the importance of recording the demographic composition of data sets and understanding label taxonomies.

So diligent documentation will help reinforce accountability but also provide developers a body of evidence that can be referenced if a product crosses an ethical line, as was the case in facial recognition, she said. It became “a great basis to resist.”