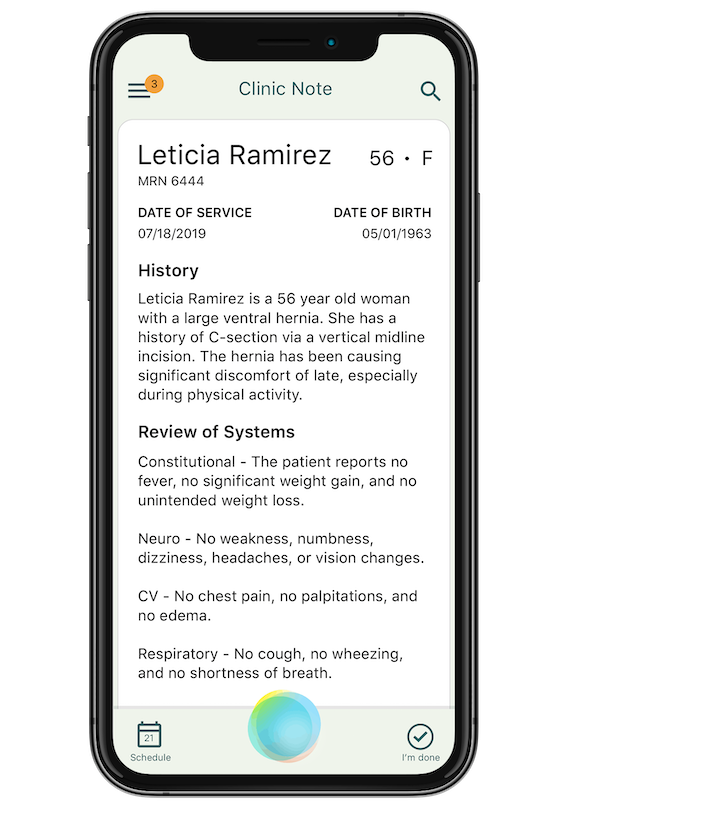

Suki, a startup that makes an AI-powered voice assistant for doctors, received two pieces of news from major clients less than three weeks ago. The first was that they’d need the product to accommodate telemedicine visits. The second was that they’d need autofilled clinical notes to quickly process patients who test positive for COVID-19 — “Hey, Suki, write up a completed clinical note for COVID-19.”

The clients sent Suki their requirements and the data they’d gathered so far, and CEO Punit Soni called a meeting with his COO, head of customer success, product lead, sales lead and marketing lead.

It was 4 p.m. The meeting lasted 20 minutes. By 9 a.m the next day, the new offerings were deployed.

To be fair, the viral outbreak had been on the team’s radar for about a month. Team members didn’t know how severe it would get or what response it would require, but they knew one thing: Healthcare professionals would need support, and AI would be one way to give it to them.

“In hindsight it’s obvious, but I hadn’t thought about how telemedicine would explode with doctors unable to see patients because of infection issues,” Soni said. “But that’s the cool part about being a tech startup. Not only are you super agile, you have the ability to create and deploy a product in 24 hours flat. All I need is data. That’s one of the big reasons why AI is the future.”

For many, the rapid spread of the novel coronavirus — and worldwide confusion about how to best contain it — makes human limitations seem more stark than ever. We can’t treat patients if we don’t have the hospital beds. We can’t curb the virus’ spread if we don’t know who has it, or if we can’t find a vaccine.

AI only knows what we tell it, but it does what we cannot: take in large amounts of disparate information and detect patterns. As we scramble to save lives and stabilize our world, some companies are using algorithms to give us an edge.

AI-enabled lung imaging helps track COVID-19’s progression

Dr. Yale Tung Chen, an emergency medical doctor in Madrid, wrote a tweet on March 9: “Day 1 after #COVID diagnosis. Sore throat, headache (strong!), Dry cough but not shortness of breath. No lung US abnormalities. Will keep a #POCUS track of my lungs. #coronavirus”

“POCUS” is an acronym for point-of-care ultrasound. Beneath the text is an ultrasound image of Chen’s lungs. The bottom right corner of the image reads, in Spanish, “Captured with Butterfly iQ.”

Some healthtech companies — like medical imaging startup Butterfly Network, the creator of Butterfly iQ — were uniquely positioned to respond to the outbreak. Butterfly iQ is a handheld, AI-powered ultrasound device that sends images to a user’s mobile phone for automated interpretation.

The startup had been monitoring COVID-19 since its outbreak in mid-January in the Asia Pacific region, where physicians were reporting the importance of lung imaging in tracking and treating the virus. Since Butterfly Network’s scanner could serve as a cleaner, less expensive alternative to X-rays and CT scans, the product’s relevance was clear to the company early on.

After noticing physicians like Chen sharing images of infected lungs on social media, the startup launched a landing page where medical professionals can share images and learn how to use the scanner for lung ultrasounds. Butterfly Network also hosted a webinar last Thursday to help healthcare workers recognize a COVID-19-positive lung.

AI comes into play in two ways. First, automated image analysis makes it easier for people with less training to use the scanner effectively. As hospitals shift assignments to manage an influx of sick patients, workers unfamiliar with the nuances of lung imaging could end up screening patients — and may benefit from a more accessible device.

Second, as more medical professionals use Butterfly Network’s scanner to check for symptoms of COVID-19, the company’s cloud-based system gets more robust data about the virus and what it looks like. That, in turn, will make the product’s analysis more accurate, director of education Dr. Mike Stone and chief medical officer Dr. John Martin wrote in an email. Martin has been corresponding with emergency room physicians in China, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom as the pandemic has progressed, he said.

“It’s an all-hands-on-deck approach right now,” the email said.

Just as important as treating infected persons, however, is making sure they don’t infect more people.

Boston-based startup Biofourmis offers an AI-powered health analytics platform called Biovitals, which uses patient monitoring to predict negative health outcomes before they happen. Biofourmis had been working with the University of Hong Kong on an at-home heart monitoring solution for two years when they received a call from the government of the region asking if the solution could be repurposed for at-home COVID-19 monitoring.

That’s because healthcare facilities are among the least safe places for sick people during a pandemic. In a February 7 study of 138 coronavirus patients in Wuhan, China, 41 percent were suspected to have caught the virus at a hospital. By keeping carriers and potential carriers at home, healthcare workers and vulnerable hospital patients are shielded from some exposure.

Biofourmis received that call in mid-February. Its solution rolled out two weeks ago in Hong Kong.

Here’s how it works: Patients who are positive or at risk for COVID-19 are equipped with a biosensor to wear on one of their arms, and then they’re sent home. The sensor collects 20 different physiological signals from its wearer, including temperature, heart rate and respiration rate. Then, Biofourmis’ platform uses AI to analyze the signals and determine if a physician needs to be pinged. Over time, the machine learning model will start to understand the physiological signature of the virus, so it ideally can be detected earlier and treated more effectively.

“We’re also collecting data right now on medication, imaging, clinical data and therapies, and we can use AI to potentially learn more about this disease, because we know very little about the disease right now,” Biofourmis CEO Kuldeep Singh Rajput told Built In. “Having AI guide us and tell us exactly what signature COVID-19 has and how it progresses will help physicians manage patients better, but also will help companies to come up with new solutions.”

Biofourmis’ predictive platform will roll out in three more countries with high COVID-19 infection rates in the next week, Rajput said. He did not disclose which hospital systems will participate.

AI can help patients with unrelated illnesses get treatment

Telemedicine, which Suki is supporting, and at-home care, which Biofourmis is enabling, could be instrumental in preventing hospital systems from becoming overwhelmed by confirmed or suspected COVID-19 patients.

But people suffering from coronavirus aren’t the only ones getting sick. Patients with other illnesses or chronic conditions — like heart disease, which accounts for one in every four deaths in the United States each year — will have a harder time getting seen by medical professionals and receiving the care they need.

That’s why healthtech startup HeartFlow isn’t adjusting its offerings at all.

HeartFlow uses AI to analyze CT images of patients’ hearts. Physicians upload the scans to HeartFlow’s cloud, and then the company’s algorithms and trained analysts create a 3D model of the heart and its arteries. With the help of another layer of physics simulations, HeartFlow provides physicians information about how blockages impact blood flow.

Usually, insights like those require an invasive procedure called an angiogram. And invasive procedures require attending physicians and hospital beds — two things in short supply during a pandemic.

“A lot of hospitals are cancelling elective procedures and things that aren’t emergencies to try to save on supplies or personal protective equipment, as well as just time and space in the hospital,” said Tim Fonte, HeartFlow’s VP of customer success. “They’re doing things as far-reaching as converting physicians’ offices into intensive care units temporarily.”

By letting algorithms do what angiograms normally would, HeartFlow is helping hospitals divert more resources toward COVID-19 response. Its analysts need special equipment, so they will continue working on-site in the Bay Area and Austin, albeit in smaller, isolated teams. The startup has a working group of about five people addressing customer concerns and determining the best path forward in light of the outbreak, but it’s largely business as usual, Fonte said.

“There wasn’t a fundamental need to change what we’re doing now,” he said. “Hospitals have to put their time into other things right now, but it doesn’t mean these patients with coronary disease who need help are just going to go away.”

Companies outside healthtech are getting involved too

Some companies leveraging AI to help aren’t in the healthtech space. In fact, they’re not even creating their own algorithms.

CRITICALSTART is a Texas-based cybersecurity startup. Its director of professional services, Quentin Rhoads, likes being the best at things — or at least close to the best, he said.

“I’m a pretty competitive individual in pretty much everything I do,” he said. “I don’t ever want to feel like I fall behind. I guess I’ve always been like that.”

Perhaps that’s why when Twitter user @TinkerSec sent him a message saying one of CRITICALSTART’s competitors was donating part of its computing power to help researchers simulate the protein structures of COVID-19, Rhoads signed his company up the same day.

The project was Folding@Home, an effort by researchers at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine to crowdsource the computing power needed to run extremely complex simulations of the atoms in viruses.

A virus is coated in protein, which consists of folded-up amino acids, which consist of atoms. Existing experimental methods provide a snapshot of a virus’ atoms, but no insight into how they move and interact. Simulations are a better way to hunt for a virus’ weaknesses, but running each simulation requires an enormous number of calculations — running them on a single computer would take hundreds of years.

That’s where CRITICALSTART’s password-cracking server, dubbed Cthulhu, comes into play. Cthulhu is a combination of hardware and software that uses eight Nvidia Titan V graphics cards — created for deep learning and AI research — to make 27.8 billion password guesses per second. Its automatically generated password-candidate lists contain quadrillions of unique entries.

With Cthulhu on the job, CRITICALSTART joined more than 240,000 teams across the world donating powerful computing rigs, or even personal laptops, to the task. In the week leading up to March 18, 400,000 people downloaded Folding@Home, director Dr. Greg Bowman said on Twitter, and the project now has 470 petaFLOPS of power available to it — more than two times the peak power of the Summit supercomputer. (Summit is the world’s fastest computer. So far, it’s found 77 potential coronavirus therapies by running simulations.)

A week after starting with Folding@Home, Rhoads is keeping close tabs on his company’s ranking.

“Right now we’re in the top 2 percent of contributors, which is pretty insane,” Rhoads said. “I mean, we’re still ranked like 5,000th globally, but still.” (Their rank had risen to 3,406th at the time of this writing.)

The CRITICALSTART team has paused the simulations to run penetration tests a few times, Rhoads said, but largely, the GPUs have been dedicated to generating data about the virus. In uncertain times, it feels good to do something helpful — and the team rankings don’t hurt either.

“This gives our team something to do that’s constructive,” Rhoads said. “We’re trying to convince our other competitors to get involved as well. It gives it a little gamification and lets us not just contribute to a good cause, but also get bragging rights.”

Could AI help predict the next global pandemic?

Despite AI’s usefulness for researchers, healthcare workers and corporate types, it has its limitations. Namely, its reliance on past data makes it an imperfect tool for responding to a novel threat. When it comes to COVID-19, AI can’t tell us what will happen next — and hasn’t really told us what’s happening right now.

The machine learning specialist tapped by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to model current infections, for instance, chose not to use machine learning, Vox reported. Instead, he’s using a method called “wisdom of crowds,” in which normal people report how they think the pandemic is progressing, and researchers compile the answers to create a model.

“The first question everyone is going to have is, ‘How can we prevent this from happening again?’” said Gabriel Musso, chief science officer at New York City-based BioSymetrics. “I think that will get a lot of deserved attention.”

BioSymetrics is an AI-enabled platform for early stage drug discovery. While he couldn’t share details, Musso said his company has multiple clients using machine learning for COVID-19-related drug discovery or triage projects.

And while machine learning models may not be able to prevent the next global virus, he said, that doesn’t mean they can’t make us better prepared.

Novelty detection is an area of machine learning in which a model learns to identify signals or data that weren’t part of its training. A model trained on a healthy person’s signals may be able to detect early signs of disease, for example. The more the model understands which signals lead to disease, the earlier it can detect warning signs. Someday, the same could be true of pandemics.

“As a society, we need to be able to understand what we’re able to predict. To that end, there’s no reason machine learning can’t be applied effectively,” Musso said. “That’s the ultimate hope for machine learning. Once you have that understanding, there’s no reason you can’t apply similar patterns for threats that can’t be identified.”

A vaccine, a physiological signature, a voice assistant, a plan — they all require data, and lots of it. As data from disparate countries with disparate practices rolls in, experts will rush to find some systemic meaning.

Hopefully, AI will augment those efforts to make us healthier and safer. And maybe next time, it will help us be ready.

“We can use the data generated through COVID to make a better argument in favor of the costs of taking preventative measures to prevent things from spreading across nations,” Musso said. “And perhaps coordinate a response that’s anticipatory.”